One fine morning, British retiree Harold Fry heads out his door at 13 Fossebridge Road to mail a letter and just keeps walking.

“'After all,' he said out loud, though nobody was looking, 'It's a nice day.'”

The letter was to a former coworker he hadn't seen in 20 years who wrote to tell him she was dying of cancer. In a leap of magical thinking, Harold believes that as long as he keeps walking, Queenie Hennessey won't die, and decides to deliver the letter to Berwick-on-Tweed in person.

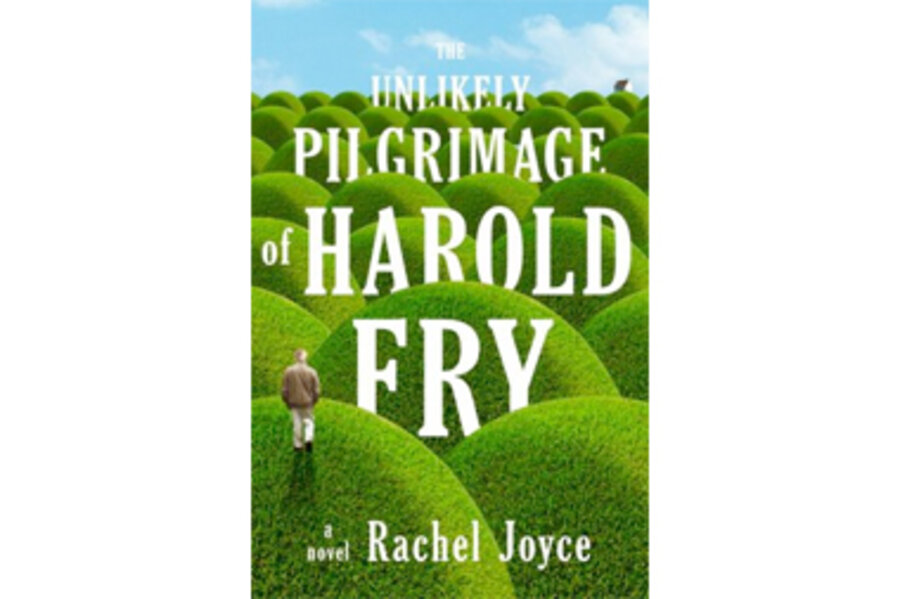

So Harold, in his boating shoes and with no supplies, becomes a modern-day pilgrim in Rachel Joyce's poignant first novel The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. The plot sounds like one of those twee independent films, where British retirees strip off for calendars or take up bank robbing in their golden years, but Joyce has deeper things on her mind than geriatric hijinks.

During his 500-mile journey, Harold undergoes enough trials to make John Bunyan's Pilgrim blanch. And his embittered wife, Maureen, has enough pent-up fury stored to utterly silence those chatty folks on the way to Canterbury. “She had bleached and annihilated every waking moment of the last 20 years.”

From the blisters to the sudden downpours, Joyce makes a reader feel every step of her unassuming hero's journey. On his way, he thinks back about the first time he met his wife, his days working with Queenie as a beer salesman, and his attempts to parent his brilliant, troubled son, David.

For Harold, the memories are more painful than the bruises, but along the way, he finds his shuttered heart opening up. As he connects with strangers who offer him meals or a bed for the night, Harold becomes an unlikely cause célèbre, a symbol of faith in a post-religious country. (And for some, a way to sell T-shirts and energy drinks.)

While the novel isn't necessarily interested in organized religion, it is most definitely concerned with the results of faith and compassion. “It was not a life, if lived without love,” a character realizes. As a mission statement, one could do so much worse.