Saburo had the kind of childhood that would make Oliver Twist hand over his porridge in wide-eyed sympathy.

The malnourished boy might have been better off as an orphan in Julie Wu's debut novel, The Third Son. While food is scarce in World War II Taiwan, his father is a savvy political operator who secures extra rations which his mother gives to his oldest brother, Kazuo. His older brothers get a private tutor, while Saburo gets beatings for coming home late.

When he's bitten by a poisonous snake, he doesn't bother running home for help. Instead, he goes to his uncle, Toru, a doctor who tries to intervene on his behalf. Saburo's mother justifies the abuse by blaming him for the death of his three-year-old brother, who fell ill after Saburo was watching him one day. He was 5 at the time.

While Kazuo gets everything he wants, there may be one exception: Yoshiko. She and Saburo met as children, when he saved her life during an air raid, and he was instantly smitten.

Saburo and Harry Potter could spend hours trading hard luck stories and both find salvation in school. In Saburo's case, there is no Platform 9 3/4. To escape, he has to pass the entrance exam that would allow him to study electrical engineering in America. The test is designed so that 99.98 percent of students fail, and none of those who passed have ever come from Taoyuan County. They certainly didn't go to a second-rate technical school. And even if he passes, Saburo would need thousands of dollars for airfare and tuition.

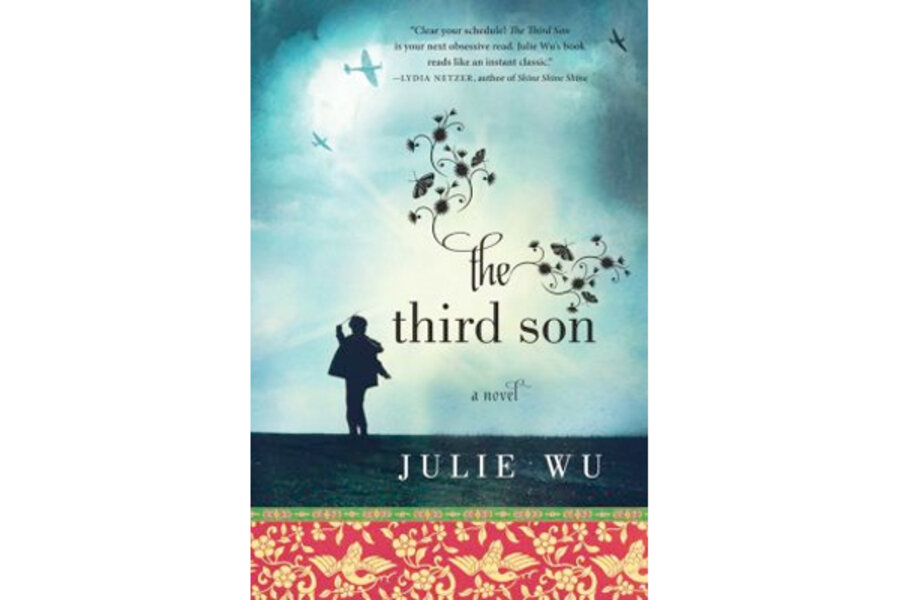

Wu's debut novel is an appealing coming-of-age story packed with vivid historical detail. Characters aren't terribly nuanced – they're either noble or loathsome. But even the Dursleys couldn't help rooting for her hero.