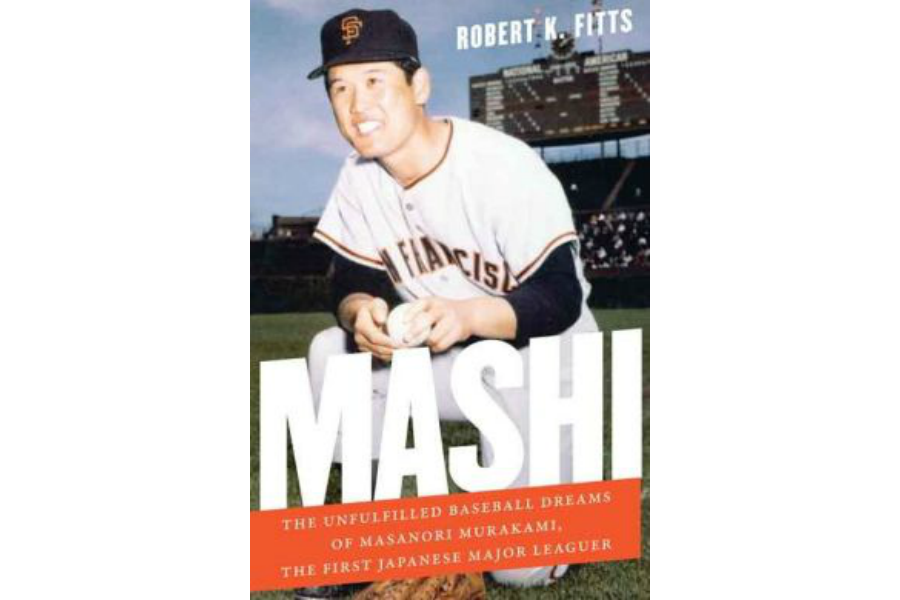

A little-remembered chapter of baseball and foreign-relations history is the focus of “Mashi,” the nickname given to Japanese southpaw Masnori Murakami. In 1965, while only 19, his Japanese team, the Nankai Hawks, sent Mashi to the Fresno (Calif.) Giants, a Class A minor league club, to sharpen his pitching skills. His performance was so impressive the Giants brought him up to the the big leagues in the 1964 during a late-season pennant race. He became one of the Giants’ most popular players, but soon found himself caught up in a dispute between the Giants and Hawks that forced Mashi to make a difficult decision to return home.

Here’s an excerpt from Mashi:

“The Giants placed Masanori and the other rookies at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel, a modestly priced establishment in nearby San Mateo, about ten miles south of Candlestick Park. Built in 1927, as the town’s top hotel, it had gradually declined and in the 1960s was used to house layover crews for United Airlines. Nonetheless, it had clean, comfortable, large rooms; a nice dining room and lobby; a recreation room; a swimming pool; and extensive grounds. It was a far cry from the Spartan Japanese baseball dormitories.

“Masanori was rarely lonely during his short time in San Francisco. The Giants’ front office reported that he received more than one thousand calls from organizations and fans asking about possible personal appearances. On his off days members of his fan club or prominent Japanese Americans took him out to eat. At one luncheon held by his booster club, Mashi eschewed the provided interpreter and did his best to answer the audience’s questions directly. Asked if he got upset when an umpire called an obvious strike a ball, he responded in English with a grin, ‘Oh, I say nothing. I just keep throwing strikes. Pretty soon umpire catch on.’ “