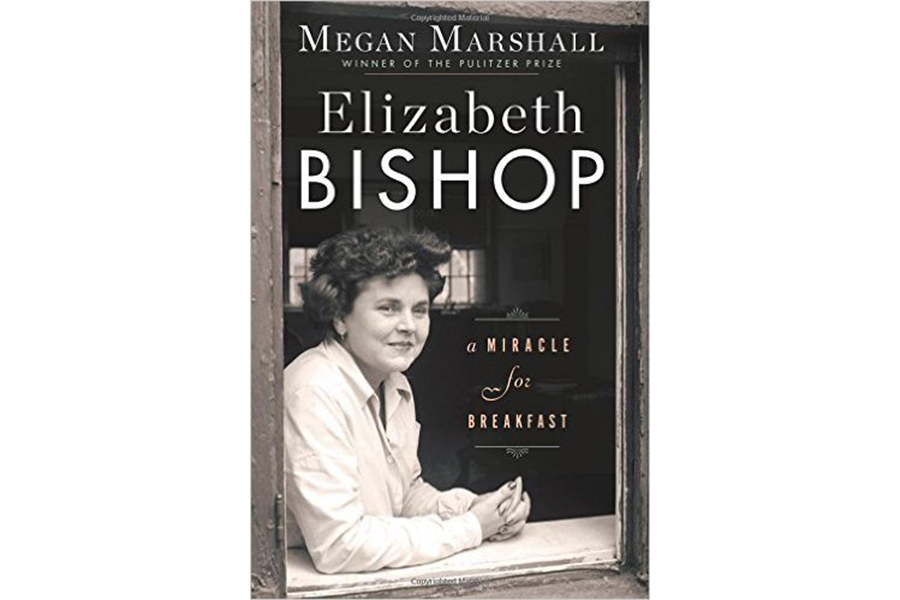

Megan Marshall's brilliant new book Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast, presents in alternate chapters Marshall's tremendously empathetic biography of her former teacher and her own memoir of her years intersecting with Bishop in Boston and Cambridge.

This combined approach creates a stunningly effective portrait of the famously elusive Bishop, who achieved immortality in American letters on the strength of a mere 100 poems but was not only shy but intensely private, particularly about her passionate love affairs with other women. Marshall's account follows Bishop from Boston's Lewis Wharf to Key West to Brazil, and readers are given rich, thoughtful looks at her relationships with editors, family, students, fellow writers (the glimpses of Mary McCarthy are particularly good) and of course other poets, including the eccentric Marianne Moore and the baleful, magnetic figure of Robert Lowell, with whom Bishop had a complicated friendship that Marshall renders beautifully.

Throughout the years of these relationships, Bishop wrote with the mostly steady chipping of reserved genius (the subject of Eleanor Cook's impressive 2016 book "Elizabeth Bishop at Work"), a process Marshall saw first-hand and understands as well as anybody who's yet written about Bishop.

“Her poetic gift had come to her early in a time of need,” Marshall writes, “and she had nurtured it, as it had nurtured her, not in the classroom but in solitude.” Bishop's friend Elizabeth Hardwick once wrote of her, “Strange things happened in her presence, emanations, a sudden effloresence that might have come from the rubbing of a lamp.” "Elizabeth Bishop: A Miracle for Breakfast" comes closer than any other book to conveying that sudden effloresence to readers who know only the famous poems and not the woman behind them.