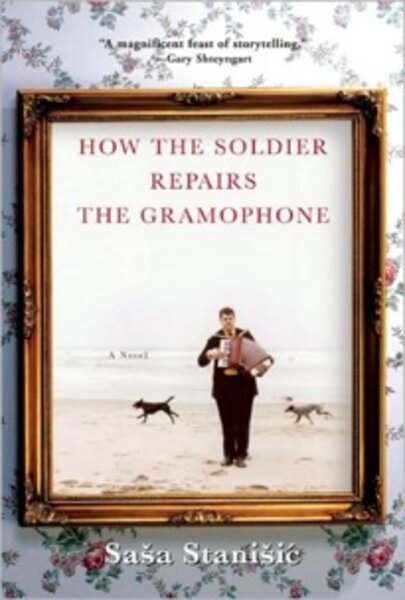

"How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone"

Loading...

Thomas Wolfe has nothing on Aleksandar Krsmanović. “You can’t go home again,” is much more than a saying once your town becomes the site of genocide, as Saša Stanišić details in his debut novel, How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone.

As a boy, Aleksandar idolized his Grandpa Slavko, who made him a hat and wand, and told him that both were magic (and only to be used in accordance with the Statutes of the Communist League of Yugoslavia).

I doubted the magic, but I never doubted my grandpa. The most valuable gift of all is invention, imagination is your greatest wealth. Remember that, Aleksandar, said Grandpa very gravely as he put the hat on my head, you remember that and imagine the world better than it is.”

Aleksandar is hard-pressed to put that imagination of his to work when his grandpa dies that very evening. Grieving, the boy decides to never finish anything again, creating 99 paintings with something left out.

“I’m against endings, I’m against things being over. Being finished should be stopped! I am Comrade in Chief of going on and on, I support furthermore and et cetera!”

Even without his Grandpa Slavko to regale him with stories on their long walks, Višegrad is still full of a motley-yet-beloved collection of relatives and friends, from Walrus, a basketball umpire whose cuckolding becomes the stuff of local legend; to Amela, a tragic figure with long black hair who bakes the best bread in town.

Then in 1992, the Bosnian war comes to Višegrad, destroying the fishing trips, plum harvests, and parties to christen indoor plumbing (parties complete with a five-piece band and a feast with dishes that go on for three pages).

Stanišić, who fled Višegrad during the war and lives in Germany, shares some of his biography with his main character. Aleksandar is also 14 when his family escapes to Essen, Germany. Before that, he watches the soldiers, who take away anyone who doesn’t have the “right” name and rape anyone unfortunate enough to attract their attention.

Hiding in the attic one afternoon, Aleksandar (who has a Serbian father and a Muslim mother) helps a Muslim girl by pretending she’s his sister. He can’t find Asija when his family escapes a few days later and is haunted by her for years.

Once in Germany, Aleksandar briefly describes his family’s poverty and struggles to adapt to their new lives as refugees. But then his grandmother gives him a journal and a request: “you have to remember them both ... the time when everything was all right and the time when nothing’s all right.”

Writing down the stories he collected during his boyhood, Aleksandar realizes, “I don’t have to invent anything to tell a story of another world and another time,” and carries the reader back to Višegrad.

Those stories range from a gleeful fish tale (a yarn involving a catfish and a pair of spectacles that could have come out of Twain) to the village’s embrace and then rejection of an Italian engineer who worked on the local dam.

The chapters follow the stream-of-consciousness style of the novel, with long lists of disparate-sounding headings such as “When flowers are just flowers, how Mr. Hemingway and Comrade Marx feel about each other, who’s the real Tetris champion, and the indignity suffered by Bogoljub Balvan’s scarf.”

In the first half of “How the Soldier Repairs the Gramophone,” the horrors of the war are shown through the baffled eyes of a sensitive and naive child. This can lead to a frustrating confusion for readers, since it’s difficult to parse together exactly what’s happened to individual characters – a problem rendered more difficult by the purposely chaotic structure and Stanišić’s fondness for repetition and lists. After finishing the novel, I can’t say for certain what Aleksandar’s Uncle Miki was involved with, except that I’m pretty sure it wasn’t good.

After the grown-up Aleksandar comes back to Višegrad in 2002, the stories have a more adult bitterness to them, such as one detailing a soccer game between opposing forces where the ball ends up in a minefield and the cease-fire ends at halftime.

Stanišić splinters apart his plot, completely ignoring linear sequence and sometimes starting a new story without finishing the first. At its best, the result is like a shivered mirror – each fractured piece showing a different fragment of horror or memory.

Readers who appreciate a conventional story line are likely to be nonplussed; fans of more experimental writers such as Michael Ondaatje will want to pick up this deeply felt debut.

Yvonne Zipp regularly reviews fiction for the Monitor.