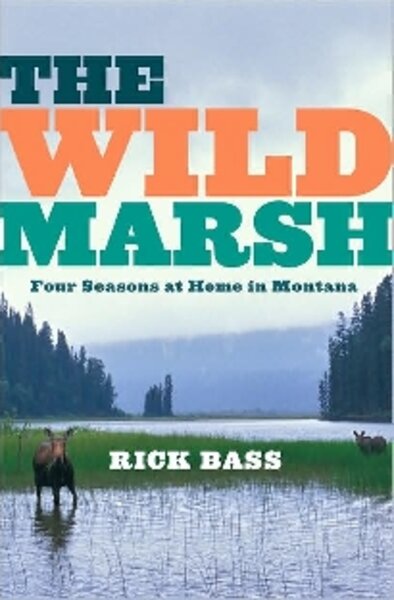

The Wild Marsh

Loading...

Many nature writers, for whatever reason, feel compelled to stray far afield from terrain they know intimately with their eyes and heart. But not Montana’s Rick Bass.

It’s now the middle of summer and, like glacier lilies peppering the Western mountains, the Yaak Valley’s man of words and woods is back with another book waiting to take readers away to one of the least populated corners of the American landscape.

By making his adopted dell a muse for different kinds of works – from fictional short stories to activist essays – Bass has left the Yaak indelibly stenciled into the map of literary place names. His prolific prose and its singular yet multidimensional connection to one million acres of geography have caused critics to herald him as a modern version of Henry David Thoreau. But here we must ask a question: What more do we need – and want – to know about the Yaak that Bass hasn’t been revealed to us before?

To quote Thoreau (who found plenty of fodder for universal rumination at local Walden Pond and in Maine’s nearby North Woods): “It is not worth the while to go around the world to count the cats in Zanzibar.” Translation: One doesn’t need a dog-eared passport; a huge travel budget, a large amount of ennui, and an abundance of elusive vacation days to discover the sacred, the exotic, and the profound.

If this sounds trite, perhaps even preachy, Bass shows us why it isn’t.

In The Wild Marsh: Four Seasons at Home in Montana, he counts, and takes stock of, lots of different things found in his own backyard; among them the tracks of wildcats, grizzly bears, wolves, deer, moose, and elk that have prowled the forests of the Yaak since the last Ice Age. The latter also give the author some of his sustenance.

As a father, he and his wife watch their young daughters pass from a pre- to post-9/11 era, though in many ways they grow up unaffected by the dissonance of the outer world. Their lives are sculpted by the same phenomena that carved out the rugged physical terrain that engulfs them.

Rummaging through the understories of ancient trees and boulder-strewn river washes, set, in turn, against the profile of his family members, Bass responds to nuanced changes wrought by humans and climate in the natural panorama around him – some that he can effect, others beyond his influence.

More than 20 years ago, Bass, then a budding novelist and former geologist from Houston, retreated to the Yaak in strident pursuit of isolation and purpose. He found it. His obscure outpost in extreme northwest Montana could be considered a rugged extension of the southern Canadian Rockies. It lies along a road to nowhere.

While Bass’s earlier works of nonfiction, including “The Book of Yaak” (1997) and “Why I Came West” (2008) have, more or less, represented moving arguments for saving nature from industrial logging and mining, he makes it clear that here he isn’t climbing the activist’s soapbox. This book is more a pure reflection on natural history and a bittersweet calendar of remembrance.

In fact, “The Wild Marsh” succeeds in one respect far better than Bass’s earlier tomes. Its resonant strength is Thoreauvian; it promotes the notion that fleeting time can be magically slowed down, its essence cherished and distilled, but only if one makes – and consciously takes – the time to observe the miracles of nature that occur outdoors each day.

“There are times when I forget my fear for the future of this landscape, and when I exist only in the green moment,” he writes. “And maybe that’s what this narrative is about: trying to isolate those moments from the periods of nearly daunting fear, and even outrage.”

Begun back in the 1990s, “The Wild Marsh” shows how Bass learns to dwell in daily unscripted events, shaped by the seasons, and how this enables him to inch closer to the things that matter, and to worry less.

Baby Boomers take note: Bass transforms the Yaak into a meditation on aging, one perfectly suited to summer, representing for him the bridge between rising youth and senescence. “My life, I realize suddenly, IS July,” he declares. “Childhood is June, and old age is August, but here it is, July, and my life, this year, is July inside of July.”

Like Thoreau’s 19th-century essays, which still represent touchstones, Bass hopes that scientists, 100 years from today, will get a sense of how one observer existed at the head of a wild valley with global forces bearing down upon it. His contribution to the future: pure wonderment.

Indeed, many gifted nature writers go try to find themselves in Zanzibar. Not Bass. He rightly assumes the role of America’s 21st-century Thoreau. “The Wild Marsh” is his tribute to staying at home.

For those who want to be transported to an extraordinary place beyond the suburbs, this book offers the sensations of a cross-country pilgrimage to a wild destination over hither and yon, commencing with snow and ice, passing through the euphoria of spring, the wistfulness of summer, and the blazing colors of autumn before arriving, back where the author started, on New Year’s Eve.

Oh, what a journey. Bass’s escape to the Yaak, once more, is ours, too.

Todd Wilkinson lives in Bozeman, Mont., and is writing a book about Ted Turner.