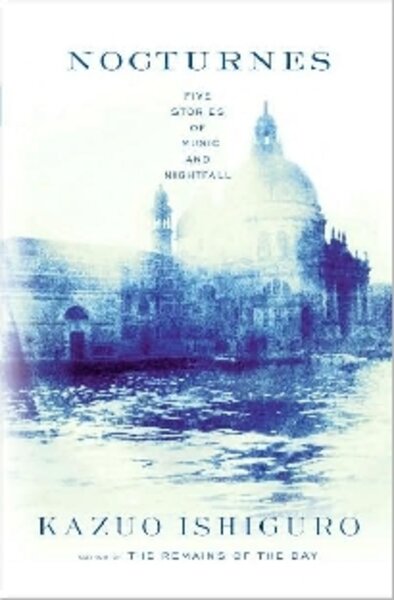

Nocturnes

Loading...

It’s pretty wonderful when an established author still has the capacity to surprise readers after more than two decades and six novels – as Kazuo Ishiguro does in Nocturnes, his first book of short fiction.

Ishiguro has tackled the theme of the banality of evil from multiple angles, most notably in characters so wrapped up in the minutiae of their quotidian lives that they fail to assess the darker, big picture – like the devoted butler in his Booker-Prize-winning third novel, “The Remains of the Day” (1990), and the students in his most recent, disturbing dystopia, “Never Let Me Go” (2005).

Compared to his novels, “Nocturnes” is light – but by no means lightweight. It is a cycle of five not-quite-novella-length stories linked by a shared concern with striving musicians and the challenges of art and love. His characters aspire to greatness yet scramble between hard, disappointing gigs playing saxophone, cello, or guitar for tourists in hotels or the Piazza San Marco in Venice. Their compromises raise questions about what defines success.

Although these stories, too, involve people absorbed in their narrowly focused interests, the confusing, surreal atmosphere that blankets “The Unconsoled” (1995), Ishiguro’s novel about a renowned pianist, is largely absent.

Written in the first person, with a strong sense of voice, these stories – like his novels – also end largely on a note of resignation. But they are filled with dialogue, conversations between aspirants and has-beens that capture the eagerness for praise that drives these insecure performers.

Two of the best stories, “Crooner” and “Nocturne,” capture the crassness of ambition and the unfathomability of others’ relationships. Both involve Lindy Gardner, the wife of a once-famous American singer, Tony Gardner. In “Crooner,” an itinerant guitarist named Janeck from a former communist country spots Gardner in a café while playing with a band in the Piazza San Marco. After Janeck tells Gardner how much his mother cherished his records behind the Iron Curtain, Gardner asks Janeck to do him a favor: accompany him on his guitar while he serenades Lindy, his wife of 27 years, from a gondola beneath her hotel window.

When Lindy responds to her husband’s renditions of “I Fall in Love Too Easily” and “One For My Baby” with audible sobs, Janeck can’t understand what is going on between Gardner and his wife. Even after Gardner explains the sad reason for his romantic gesture – a swansong to an aging partner being traded in for a younger model who will be more advantageous for his planned comeback—Janeck, from another culture, remains baffled.

Going to appalling lengths to boost one’s career also factors in “Nocturne,” an alternately sad and hilarious story about Steve, a “loser ugly” saxophonist who undergoes extensive plastic surgery – persuaded by his manager, who thinks it will advance his career, but really hoping to win back his estranged wife, who gets her rich boyfriend to fund the operation.

While convalescing in a Beverly Hills hotel with his face encased in bandages, Steve meets Lindy Gardner, famous ex-wife of Tony and “a person of negligible talent – okay, let’s face it, she’s demonstrated she can’t act…No other news could have symbolised more perfectly the scale of my moral descent. The week before, I’d been a jazz musician. Now I was just another pathetic hustler, getting my face fixed in a bid to crawl after the Lindy Gardners of this world into vacuous celebrity.”

Trapped and bored, Lindy and Steve fall into touchy discussions about what constitutes talent and success. When he joins her on one of her nocturnal rambles around the posh hotel, they are stopped and questioned by hotel security and end up onstage at a hotel convention with an arm up a turkey – a cross between surrealist slapstick and bad dream sequences reminiscent of Haruki Murakami’s novels and Ishiguro’s “The Unconsoled.”

Ishiguro captures a similarly impressive range of emotions in “Come Rain or Come Shine,” another by turns devastating and funny story about a man who feels like a loser. Like several of Ishiguro’s characters, Ray is drawn into a married couple’s dynamic that he’s slow to fully grasp. He ends up in a ridiculous situation that somehow highlights his humanity and makes him all the more sympathetic.

Like the Chopin pieces their title evokes, Ishiguro’s “Nocturnes” are deceptively simple, expressive and harmonic, delicate yet substantive. Never mind his characters: Ishiguro is the true virtuoso performing here.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.