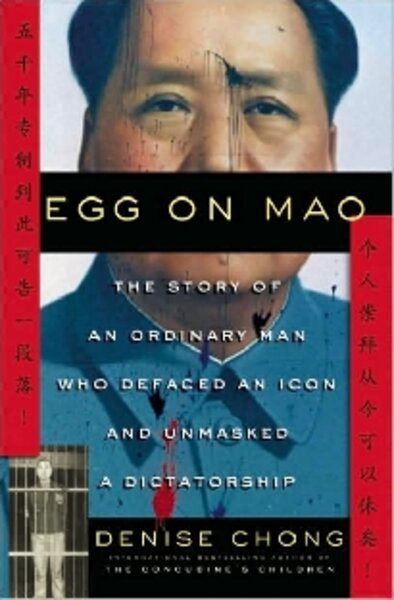

Egg on Mao

Loading...

Denise Chong has built an award-winning career capturing ordinary people living extraordinary lives. “The Concubine’s Children” (1994) told of her own family’s fractured journey from China to Canada and “The Girl in the Picture” (2000) detailed the harrowing story of the young girl whose screaming, naked image became a devastating symbol of the Vietnam War.

In her latest book, Egg on Mao: The Story of an Ordinary Man Who Defaced an Icon and Unmasked a Dictatorship, Chong bears witness to the life of a Chinese bus mechanic who risked everything in an effort to change his country’s repressive regime.

On June 4, 2009, three friends – Lu Decheng, Yu Zhijian, and Yu Dongyue – were reunited in Washington, D.C., to mark the 20th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. All three had spent the majority of the past two decades in scattered prisons, united by a single pledge to each another: “I must leave this prison alive and with my sanity.” Those of us fortunate enough to live in a free country can hardly comprehend that throwing paint-filled eggs on a poster could result in endless years of subhuman imprisonment.

Part biography, part history, part testimony, “Egg on Mao” closely follows the story of Lu Decheng, one of the three reunited friends. Chong weaves together several narrative strands: Lu’s early life in his riverside village in Hunan Province (modestly famous as the birthplace of fireworks); his fateful act of political protest during a pivotal moment in modern history that traps him in the Chinese prison system; and his subsequent survival and release, with his humanity somehow intact.

Growing up under a crushing Communist system that remained unchallenged even after Mao’s 1976 death, Lu was mostly raised by his beloved grandmother. Officially classified as a “martyr’s widow,” which accorded her certain privileges under the fickle regime, Grandmother Lu repeatedly emphasized the need for people to maintain the ability to “think for themselves.” Her dangerous but truthful talk of high-ranking thievery, deceit, and execution shaped Lu’s defiant views.

By the time the Beijing student uprising went public in spring 1989, Lu was anxious to participate. He had suffered incomprehensibly from senseless regulations. His experiences included being forced to live on the run, bribing another couple to avoid a forced abortion for his young wife, and losing an infant son when he didn’t have the documents required to receive proper medical treatment.

Lu saw his opportunity to make a public protest when nine young men named themselves the “Hunan Student Movement Support Group, Liuyang Branch” and planned the trek to Beijing. They realized that “the opportunity to advocate so openly for democratic reform might never come around again in their lifetime.”

Of the original nine, four arrived in Beijing, and only three actually planned and executed the May 23, 1989, splattering of 30 paint-filled eggs across the behemoth poster of Chairman Mao in Tiananmen Square. The trio believed “[t]hey had targeted an icon to challenge the despotic rule of the regime.” They expected their actions to incite further protest: “Now it was up to the student leaders to mobilize the people and make them see that, like the stained portrait of Mao, the dictatorship was flawed, even finished.” The student leaders, however, delivered Lu and his friends to the police, beginning an odyssey of personal tragedy and the fight for ultimate survival.

Lest a reader question Chong’s research, she includes a detailed “Author’s Note” on how she gathered interviews with Lu, who now lives in Canada. She spent two months in China in 2007 where “a complete ban remains in place against discussion of the protest and events in the square and the subsequent brutal crackdown and repression.”

In a post-Olympics China, where the world converged on 8-8-08, where major international companies vie for market share, where some of the world’s brightest young men and women are establishing ambitious careers, and where reverse immigration is a common occurrence with members of the Chinese diaspora returning “home” for greater opportunities, a story such as Lu Decheng’s seems virtually impossible.

And yet, ironically, Chong was in China on the 18th anniversary of the threesome’s act of protest, when an unnamed man was arrested for throwing a burning rag at Mao’s still-looming portrait in Tiananmen. He was pronounced “insane.”

Terry Hong is media arts consultant at the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Program. She writes a Smithsonian book blog at bookdragon.si.edu.