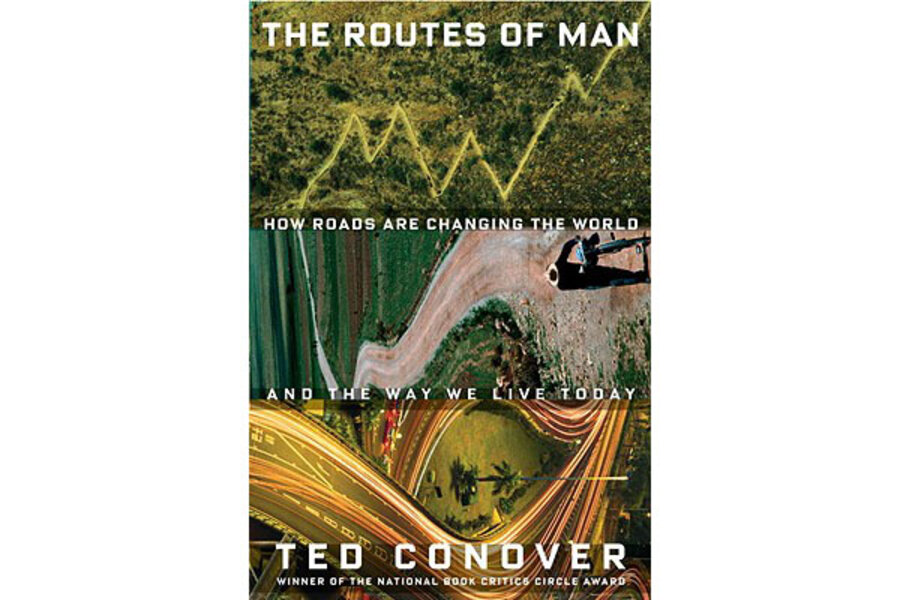

The Routes of Man

Loading...

The Routes of Man is a largely engaging inquiry into how roads affect economics and social change. Ted Conover has no fear of remote, even dangerous places. His curiosity is admirable, his style high. The lesson of “Routes” – the fruit of Conover’s adventures over the past two decades in Peru; the secretive, northern Indian region of Ladakh; East Africa; the West Bank; China; and Lagos, Nigeria – is that roads, no matter how straight, aren’t exactly linear. Neither is the book, which can be distracting.

While “Routes” features marvelous descriptions of places most people either can’t afford to reach or are scared to visit, it’s short on interpretation. I wanted Conover to tell me not only how roads are changing the world, but also how we might accommodate them with minimal environmental damage. Instead, he seems satisfied with the trip itself, shying from speculating on topics like the consequences of building a road between Tibetan-influenced Ladakh and lower

India where the only passage now is over ice, or of the rapid, congestive spread of American-styled car culture in China.

“Roads remain the essential network of the non-virtual world,” he writes. “They are the infrastructure upon which almost all other infrastructure depends. They are the paths of human endeavor.” Such eloquence suggests interpretive adventure. Instead, we often get digression.

I wanted an explanation of the network of roads, the biggest “human-made artifact on earth.” Instead, I got probes of exotic lifestyles, an appreciation of how effectively Conover embeds himself in the cultures he studies, and distinguished prose. (That’s no surprise considering he won the 2001 National Book Critics Circle Award for “Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing.” He was also a finalist for that year’s Pulitzer Prize.)

Yet an attitude bordering on the fatuous pops up in his first section, about the role roads play in the mahogany trade in Peru. Conover is in Cuzco, marveling at the masonry of an Inca wall: “When a vendor with beautiful waist-length braids, necklaces, and a funky velvet top hat demands payment for having her photo taken, you can understand why but are put in mind of the continuing indignity of the Indians, the evident absence of skills as sublime as those of the ancient stonemasons.”

A few pages later, however, comes this sublime passage as Conover describes a scene east of Cuzco: “The view was still limited until one particular turn revealed the sudden vista, one of those spectacular places through which you come to understand the shape of the planet: the wrinkled green mountainsides spread out before us, dissolving suddenly in the vast, smooth green sameness of the Amazon basin, a flatness that stretches two thousand miles to the sea.”

Lovely writing abounds in this vivid, if flawed book. So does ambivalence, as Conover shows but doesn’t parse the links between roads, the societies in which they develop, and the markets they represent. Such connections often are grey areas: In Lagos, for example, roving bands of poor kids called “area boys” live on and off roads. Without the roads, however, the boys wouldn’t have even the gangster lifestyle which now (barely) sustains them.

Conover suggests that trade in mahogany – the wood at the heart of extraordinary custom furniture in swanky apartments in New York’s “high WASP” Upper West Side – will lead to environmental damage if roads are built to continue to enable its transit. He posits that trucking in East Africa enabled the spread of AIDS, which won’t abate until sex education takes hold. In Ladakh, he speculates that building a road might consolidate India but aggravate its enemy Pakistan, even as it opens the area to new influences and market opportunities. In the West Bank, he puts us inside checkpoints, detailing how separate roadways keep Palestinians and Israelis apart, though not more secure. In China, he puts us behind the wheel of Zhu Jihong, a car nut who loves communal “self-driving tours” (it’s a slow ride). And in the final and most colorful section, we accompany him in ambulances in Lagos, a Nigerian megacity where roads are so congested that they become bazaars.

The armchair tourism is excellent, and Conover ends with a wonderful epilogue weaving every road cliché you’ve ever read into a meditation on the notion of neighborliness and the necessity for movement. Not a bad trip if you can handle the detours.

Carlo Wolff is a freelance writer from Cleveland.