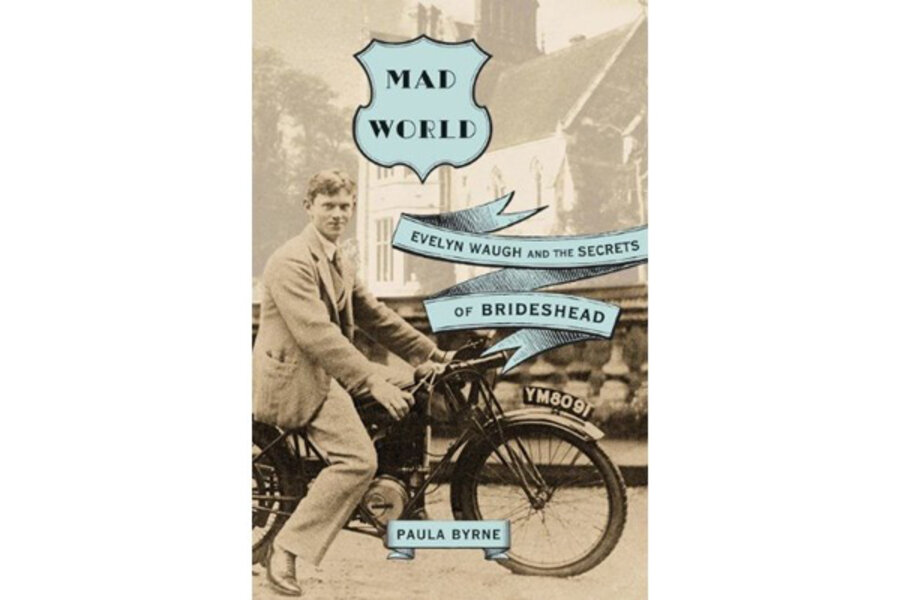

Mad World

Loading...

A few years after publishing his most sentimental and autobiographical novel, “Brideshead Revisited,” in 1945, Evelyn Waugh satirized its plot in his prizewinning war trilogy, “Sword of Honour,” referring to it as “Shakespearian in its elaborate improbability.” The truth, however, as Paula Byrne makes vividly clear in Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead, is that the real story behind Waugh’s top-selling novel is even more fantastic than his fictionalized distillation.

Byrne’s engaging book will resonate especially for those who fondly remember Granada Television’s consummate 1981 adaptation of “Brideshead Revisited,” featuring Jeremy Irons, Sir Laurence Olivier, Claire Bloom, and Sir John Gielgud.

“Mad World” is part of what Byrne flags as a growing 21st-century trend in literary biography toward the “partial life” – as opposed to “the heavily footnoted biographical doorstopper [which] had its heyday in the second half of the 20th century.” Freed from “the shackles of comprehensiveness,” biographers explore their subjects via a seminal theme, year, or event. The result, at least in this case, is more streamlined and focused, but still remarkably thorough.

Byrne, the author of “Perdita: The Literary, Theatrical, Scandalous Life of Mary Robinson” and “Jane Austen and the Theatre,” embarked on “Mad World” determined to correct what she considered to be Waugh’s persistent misrepresentation “as a snob and a curmudgeonly misanthropist.” She marshals friends’ testimonials and previously unpublished letters to resurrect both his literary and personal standing.

In the course of her research, Byrne realized that “his relationship with a single family: the Lygons of Madresfield ... provided a key that could unlock the door into Waugh’s inner world.”

Waugh, like the narrator pf “Brideshead,” Charles Ryder, was born into a middle-class family in 1903. His father worked in publishing. Both attended second-tier boarding schools, and then Oxford in the early 1920s on scholarship. Waugh was unhappy there until a friend introduced him to the Hypocrites, a drinking club whose elite members were high-spirited in every sense of the word.

Among Waugh’s intimates was the charming, heavy-drinking Hugh Lygon, second son of the seventh Earl of Beauchamp – a model for Sebastian Flyte in the novel, who also succumbs to alcoholism. Byrne posits that he was one of Waugh’s three homosexual relationships at Oxford. Drawn to beautiful, fragile boys – and later, beautiful, fragile women – Waugh considered homosexuality a passing phase in his development. Byrne examines the “secret that dared not speak its name,” particularly prevalent at all-male schools, with sensitivity and more than passing consideration.

Unlike his aristocratic friends, Waugh needed to earn a living after leaving Oxford. After a short stint teaching, he followed his older brother Alec – who had published a bestselling novel while still in his teens – by creating a splash with his very first novel. “Decline and Fall” captured the zeitgeist of the disaffected “bright young things” of his generation, caught between two great wars.

Throughout his life, Waugh retreated from society periodically to either gather material or write. He was enormously prolific, turning out a book every year or so, including such trenchant novels as “Vile Bodies” and “A Handful of Dust,” several prize-winning biographies, and books about his dangerous travel adventures in Africa, the Arctic, and South America.

For more than a decade – until his 1937 marriage – Waugh did not maintain a home but instead bounced among friends. Chief among these were Hugh Lygon’s sisters, Sibell, Mary (Maimie), and Dorothy (Coote), whom he befriended in 1931 and stayed close to until his death in 1966. Madresfield Court, their imposing ancestral estate in Worcestershire, was affectionately called “Mad” – hence Byrne’s title.

As another friend, writer Nancy Mitford, commented after first reading “Brideshead,” it was, “So true to life being in love with a whole family.” As smitten as he was with Hugh and his sisters, Waugh was also taken with their cultivated father. He was much affected by Lord Beauchamp’s plight: a leading liberal politician forced into exile for homosexuality. (In “Brideshead,” the source of Lord Marchmain’s disgrace was altered to an exotic mistress.)

Among the papers Byrne gained access to for the first time is Countess Beauchamp’s 1932 petition for divorce, which had been sealed through 2032 and which explicitly spells out her husband’s many homosexual liaisons – at a time when homosexuality was still a crime subject to prosecution in England.

As Byrne makes clear, Madresfield was Waugh’s Arcadia, encapsulating his “search for an ideal family” and his lifelong “theme of exile and exclusion.” Waugh’s world changed irrevocably with World War II – which explains the elegiac nostalgia that suffuses “Brideshead.” Deftly interweaving biographical details and textual analysis, Byrne makes the connections between Waugh’s art, Roman Catholic faith, and life dance.

Heller McAlpin, a freelance critic in New York, is a frequent Monitor contributor.