Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock

Loading...

The other eight black students got the message the night before the big September day in 1957: We’re going together to Little Rock’s Central High. But no one remembered to tell a quiet and brainy 15-year-old who wanted to go to a better school so she could have a better life, maybe even become a lawyer. So she walked to campus alone, meeting a vicious crowd of white faces and wicked words.

“For the moment,” writes David Margolick in Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock, his powerful and extraordinary new book, “she was the Little Rock One.”

“Don’t let her in!” someone in the crowd shouted. Casting her eyes around in fear, Elizabeth Eckford sought help from an old white woman, who returned her desperate glance with a gob of spit.

More insults. More threats. “Lynch her! Lynch her!” A curvy young woman in a tight dress spouted the n-word. She opened her mouth again. “Go back to Africa!”

Hazel Bryan looked like an adult, but she was actually only 15, too, a girl obsessed with boys and movie stars. She was caught up, she later said, in the moment. “As soon as her words had dissolved in the torpid September air, she had forgotten all about them.”

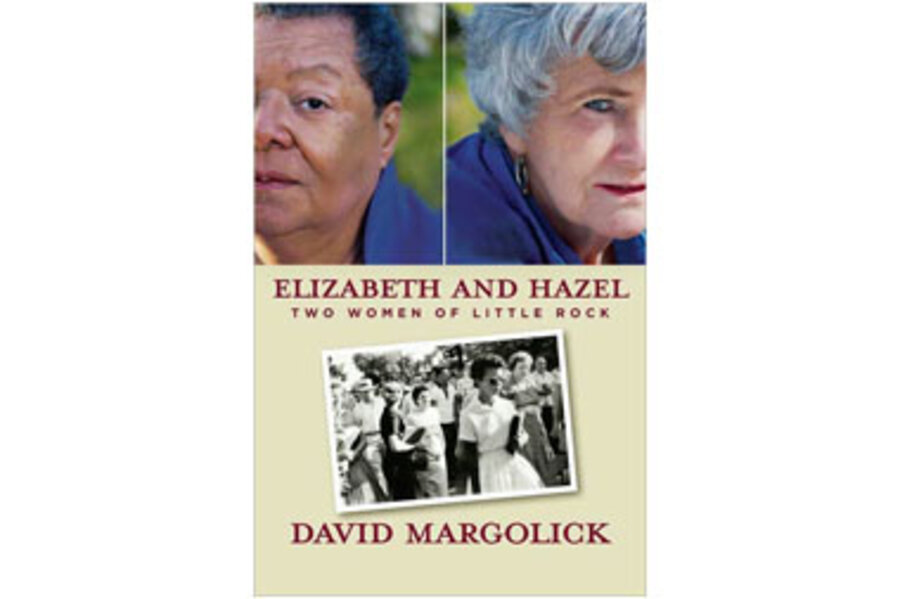

Hazel went to play hooky. Elizabeth tried to find her mother. The photographer, a skinny 26-year-old, went back to the newsroom and developed one of the most famous pictures of the 20th century.

That photo. It shows a rigid and expressionless Elizabeth, her emotions hidden forever behind sunglasses. Hazel is there, too, her mouth open in mid-hate.

That photo. It would inspire countless people to try to improve the world, including an Arkansas native named Bill who would one day host both Elizabeth and Hazel at the White House.

That photo. The image that would brand and haunt and define these two girls for the rest of their lives.

Armed with a perceptive eye and a sensitive heart, Margolick brilliantly tells the story of Elizabeth and Hazel. He chronicles a key moment in American history and its complex aftermath, inserting readers into an intensely personal story of two women caught in history’s web.

Hazel apologized to Elizabeth a few years later, and both moved on with their separate lives. One of them takes an unlikely turn into New Age eccentricity, filling her life with inspirational sayings, liberal causes, and generalized do-gooding. The other, a deeply intelligent woman plagued by crushing unhappiness and a horrific stint at Central High, alienates those around her and appears destined to end up in an early obituary.

These women are destined to meet again, however, and become a symbol of racial reconciliation. It’s here that their story becomes even more complicated and emotionally wrenching.

As a white Jewish Yankee, Margolick is the exact kind of journalist that 1950s Arkansans viewed as the worst kind of outside agitator. On top of that legacy, there’s another challenge: Elizabeth and Hazel are weary of reporters, weary of talking.

But Margolick, the author of previous books about race, manages to gain enough trust to present an amazingly intimate portrait of their inner lives.

“Elizabeth and Hazel” has some of the makings of an Oprah Book Club selection, but it’s not likely to be one. Oprah Winfrey, who brought both women onto her show, is one of many people who seem unable to believe Hazel is no longer that vicious teenager. Ms. Winfrey looks bad, and she’s got plenty of company on that front among many of the other individuals featured in the book.

Now a black civil rights activist, the woman whose memory lapse put Elizabeth in her lonely position comes across as a craven opportunist. Many of 1957’s white students at Central High portray their past in a rosy haze of denial; some resent Hazel and think of her as “a tick who had burrowed under their skin forty year earlier, and would simply not let go.” Others even now refuse to acknowledge how they responded with hatred or indifference to the strangers in their midst.

While they remain legitimate heroes, the Little Rock Nine didn’t grow up to be sterling icons of perfection themselves. But as Margolick notes, it may be unrealistic to expect people who have shown great courage to be ideal in every other way, too.

In an interview, Hazel – who found herself forever linked to a single wrong action – put it this way: “There’s more to me than one moment.” The lesson of “Elizabeth and Hazel” may be that we shouldn’t define other people’s lives by one single moment.

Instead, we can use their actions to define other lives – our own.

Randy Dotinga is a regular contributor to the Monitor’s books section.