Loverly

Loading...

On February 4, 1956, My Fair Lady was performed for the first time, at out-of-town tryouts in New Haven. Except it almost wasn't. Rex Harrison, starring as Professor Henry Higgins, was inexperienced as a singer – his lines in the show are a cross between speech and song – and the prospect of having to make his voice carry over a full orchestra spooked him. He refused to go on, and at six o'clock the theater sent out announcements over the radio that the performance would be canceled – fortuitously, there was a blizzard that night, which provided a good excuse. But the audience showed up regardless, and it was up to Harrison's agent to give him an ultimatum: "No matter what happened that evening on stage, he said, Rex damn well had to go on."

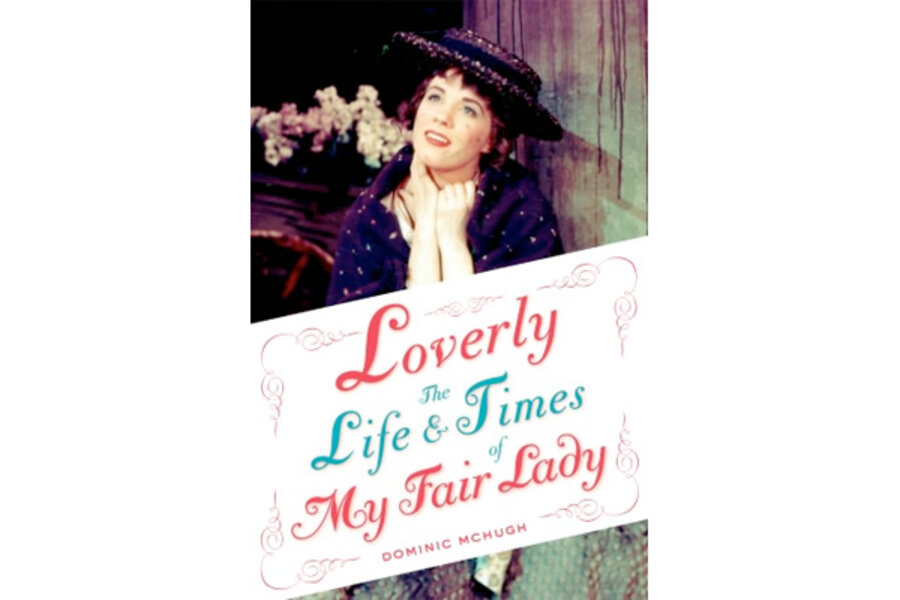

Finally he did, forty minutes late, and the result was Broadway history. From the very first night, Dominic McHugh writes in Loverly: The Life and Times of My Fair Lady, My Fair Lady was recognized as a smash in the making and a classic of the American musical theater. McHugh proves it by the numbers: "The original Broadway production ran for more than six years and 2,717 performances, and in doing so overtook Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma! to become the longest-running Broadway show to date." The cast album of My Fair Lady, featuring Harrison, Julie Andrews as Eliza Doolittle, and Cockney stalwart Stanley Holloway as Eliza's father, was the first LP to sell more than 2 million copies, then to sell more than 3 million. At the height of the Cold War, even the Russians wanted to see it: in 1960, it ran for fifty-six sold-out performances in the USSR.

In Loverly, which appears in Oxford's Broadway Legacies series, McHugh delves deep into the archives to provide a richly detailed account of the creation of My Fair Lady. Alan Jay Lerner, lyricist, and Frederick Loewe, composer, had several shows to their credit, including the hit Brigadoon, when they started exploring the idea of a musical based on George Bernard Shaw's play Pygmalion in 1952. But after complicated negotiations over the rights and the role of Eliza – which was initially destined for Mary Martin, star of South Pacific – the partners abandoned the idea and even broke up for a while. When they came back to it two years later, they toyed with casting Noël Coward as Higgins and Judy Holliday as Eliza but quickly zeroed in on Andrews and Harrison, who would become indelibly associated with their roles.

All this makes good backstage gossip, but the heart of Loverly is an earnest analysis of the ways Lerner and Loewe transformed a well-known play into an independent musical. Using music manuscripts and draft scripts, McHugh shows how Lerner and Loewe both drew on and revised Shaw's play (which itself existed in several versions, including a screenplay), and how beloved songs like "Just You Wait" assumed their final shape. McHugh concludes with a review of the major American and British productions and revivals of the show, as well as the movie version, in which Andrews was replaced by Audrey Hepburn, a bigger draw. Anyone who loves the show, or is interested in the nuts and bolts behind the golden age of the American musical, will find Loverly a fascinating read.

Adam Kirsch is a senior editor at The New Republic and a columnist for Nextbook.org.