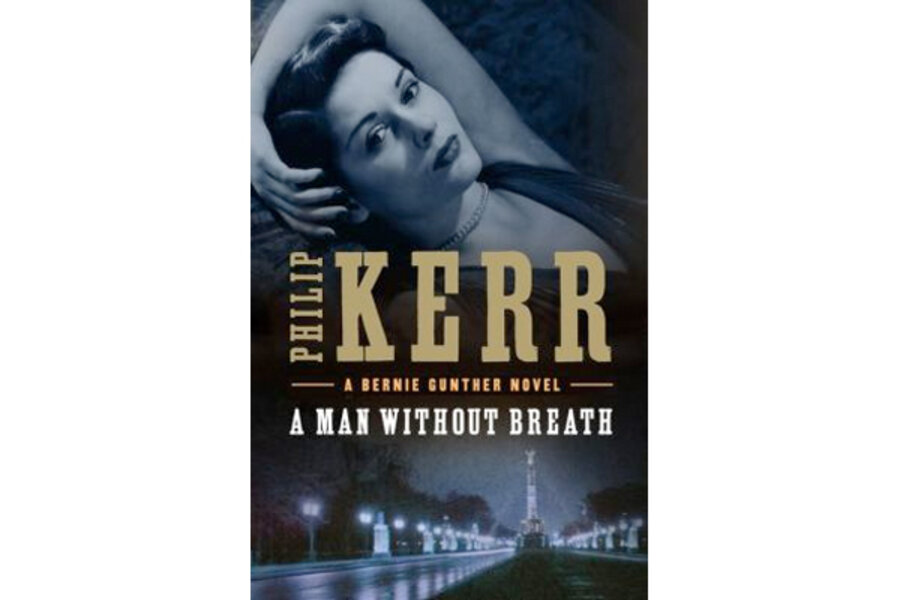

A Man Without Breath

Loading...

Philip Kerr's latest novel, A Man Without Breath, spans just three months in the spring of 1943 yet includes some of the most dramatic events of the Second World War. The German defeat at Stalingrad; the attempted assassination of Adolf Hitler; the Russian massacre of more than 14,000 Polish officers in the Katyn Forest: these are weighty matters to graft onto the slim armature of a crime novel. But Kerr is an old hand at this. "A Man Without Breath" is, after all, the ninth installment in his wartime Bernie Gunther series, and from the first, "March Violets," it was clear that he could blend formidable historical research and keen political insight to produce thrilling fiction.

Kerr is also an acute satirist. Throughout the series, employing Gunther's sardonic gaze, he portrays the chief architects of Nazi Germany and their underlings in all their brutality, venality, and shabbiness."[T]hat's the trouble with dyed-in-the-wool Nazis," Gunther observes, for instance, of a zealous Gestapo agent, "stupidity, ignorance, and prejudice always get in the way of them seeing the bigger picture. But for that they might be impossible to deal with."

As a Berlin police detective, Gunther has dealings with Heydrich, Goebbels, and other Reich leaders who are often the objects of his most caustic wit. By 1943, however, even that wit is subdued. There are fewer wisecracks in "A Man Without Breath," a novel that from the outset exudes an air of exhaustion and defeat. "[W]e're pretending that there's law and order and something worth fighting for," Gunther shouts at a Wehrmacht officer. "But there isn't. Not now. There's just insanity and chaos and slaughter and maybe something worse that's yet to come."

Following the defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943 and the Russian advance westward, the likelihood of an Allied victory seems inevitable to a tight circle of German officers and field commanders. In an atmosphere of heightened paranoia and dread, wonderfully evoked by Kerr, a report reaches Berlin of a mass grave discovered in the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, Russia. Bernie Gunther, now employed by the War Crimes Bureau (part of the Wehrmacht's legal department), is sent to investigate. "I'm supposed to make sure that this is the correct mass grave we're uncovering," he sarcastically concludes when his boss lists the possibilities: the bones could be those of Russian political prisoners; of German or Russian soldiers killed in action; of missing Polish officers; or, Gunther adds helpfully, "…of Jews murdered by the SS."

Evidence of a Russian massacre of Polish officers is what the Wehrmacht and propaganda master Joseph Goebbels, for different reasons, desire. Such an atrocity could rupture the Alliance, isolate Russia, reinvigorate German troops, and soften the victors' view of Nazi war crimes. No wonder that Gunther, his investigation hardly begun, is summoned to the Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, where his eye, as usual, misses nothing. "As Goebbels limped into the room," he observes, "I stood up and saluted in the customary way and he flapped a delicate little hand back over his shoulder in imitation of the way the Leader did it – as if swatting an irritating mosquito, or dismissing some sycophant..."

The sketch of Goebbels is one of many superb portraits. Kerr has obviously immersed himself in the manners and speech of this period, and his details are always telling; they reveal both the essence of a character, whether minor or infamous, and the texture of events long calcified into legend. The repeated attempts to assassinate Hitler, for example, woven artfully into the plot, expose the desperation of the time and the nature of the Prussian aristocrats involved. "They were just careless people…." Gunther observes of the officers. "It was their carelessness that had allowed Hitler to take possession of the country in 1933; and through their carelessness they had failed to remove him now...."

By the time he reaches this conclusion, Gunther has killed. and almost been killed, in Smolensk. (He also falls in love, but this is brief and doomed.) Even as the mass grave of Polish officers is excavated, fresh murders demand his attention; two German telephonists on duty during a brief visit by Hitler are found dead (what did they overhear?), and a key witness in the Katyn massacre case is murdered. Crimes new and old, corruption personal and political, conspiracies of all kinds: Kerr eases these components into place with his usual dexterity. But "A Man Without Breath," for all its intricacy and spark, is also Kerr's most contemplative – and substantial – novel to date. More gray than noir. The gray of ashes.

Anna Mundow, a longtime contributor to The Irish Times and The Boston Globe, has written for The Guardian, The Washington Post, and The New York Times, among other publications.