'Honeydew' showcases Edith Pearlman's originality and versatility

Loading...

Edith Pearlman didn’t so much burst upon the literary scene, as steadily chip her way into it. Why she was overlooked till so late in her career (much like the Nobel Prize-winning short story writer Alice Munro) reflects less on the quality of her writing than on our culture’s tendency to value long novels over short stories, and the image of a youthful, usually male, “genius” over the development of a refined craft and body of work over time. Big is what we celebrate. Think Jackson Pollack or Jonathan Franzen, who made the cover of Life and Time magazines.

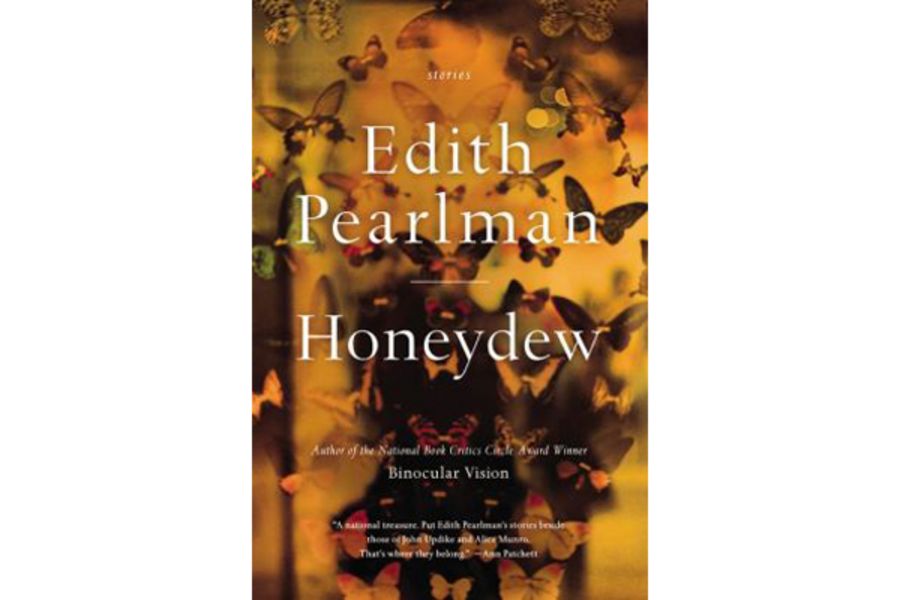

Yet, last year, Pearlman finally received the accolades she deserved for her collection of short stories, "Binocular Vision," which won great critical acclaim and a National Book Critics Circle Award. Now, she has released a new collection, "Honeydew," that continues to showcase her originality and versatility, and is sure to make her among our most renowned fiction writers.

Unlike many authors whose tales are defined by a specific geographic locale, the settings in "Honeydew" vary, ranging from an unnamed small southern town to the particularity of Manhattan’s upper west side to “Godolphin,” a fictional suburb of Boston that appears in her earlier stories. (Pearlman herself graduated from Radcliffe College and lives in the very real Boston suburb of Brookline.)

To my mind, though, Pearlman is at her best when she pulls together a web of characters in an odd, enclosed, haunted space: a historic hospital known as "the Castle," where an unlikely love affair takes place; a luxury cruise ship that contains a secret stowaway; a soup-kitchen called "The Ladle” that sets the stage for an exorcism involving gerbils (yes, really). In other words, many of these stories are wonderfully weird.

“Tenderfoot,” the first in the collection and one of my favorites, appears to set the stage for a mid-life romance for two characters who have experienced loss, but instead veers away into a stark meditation on the hurt we don’t cause, but blame ourselves for anyway. Another, “What the Ax Forgets the Tree Remembers,” seemed at first in danger of being a pedantic tale on the highly politicized issue of African female genital mutilation, but transforms into a much stranger and richer journey towards self-realization, in which two solitary women find the possibility of intimacy. This is true of many of Pearlman’s stories: There may be the promise of connection, but rarely do we see it.

Pearlman’s isolated protagonists don’t so much undergo transformations as experience dimly lit revelations, and even these moments of insight may be murky and unarticulated. In “The Golden Swan,” a young college graduate wanders away from the deck of a cruise ship to discover how the other half (that is, the people who serve her) lives. In “Dream Children,” a West Indian nanny stumbles on an odd secret kept by the father of the children she cares for, and in it finds a rare moment of mutual understanding. “Conveniences” – in which little happens, other than a couple befriending a teenage girl whose devotion leads her to help around the house – culminates in this proclamation: "'The best marriages,' said Ben, suddenly enlightened, 'have a maid.''' Some truths are just that banal, while still being true.

There is an unrelenting physicality to Pearlman’s characters, one that distinguishes her from Munro and other writers. Bodies appear with grotesquely calloused feet or erections that need hiding, with hair that’s greying at the roots or parts that need anesthetizing for surgery. Characters are punctured by a tree branch, lose their appetites and excess weight, break an ankle – and these moments are described in intimate, visceral detail. There is often the possibility of sex, and always the threat of death and decay.

Objects play an important role, too, revealing the way our exterior world is imbricated with our inner lives. The excess of a cruise ship buffet is dwelt on in repulsive detail. A minutely described wardrobe of dull, yet expensive clothes points to an aging wife’s vapidity. A plant… a statue… a stone… a series of disturbing drawings of malformed children… all serve as talismans, absorbing and emitting feelings (anxiety, love, desire, nostalgia). An anesthesiologist carries a walking stick that conceals a sword.

Through these motifs, Edith Pearlman captures some of the vastness and temporality of human experience, crafting stories that reflect the pain and possibility we carry in our memories and bodies, often emphasizing her characters’ isolation, but also suggesting some possibility for intimacy or at least, self-knowledge.

Elizabeth Toohey is an Assistant Professor of English at Queensborough Community College (CUNY).