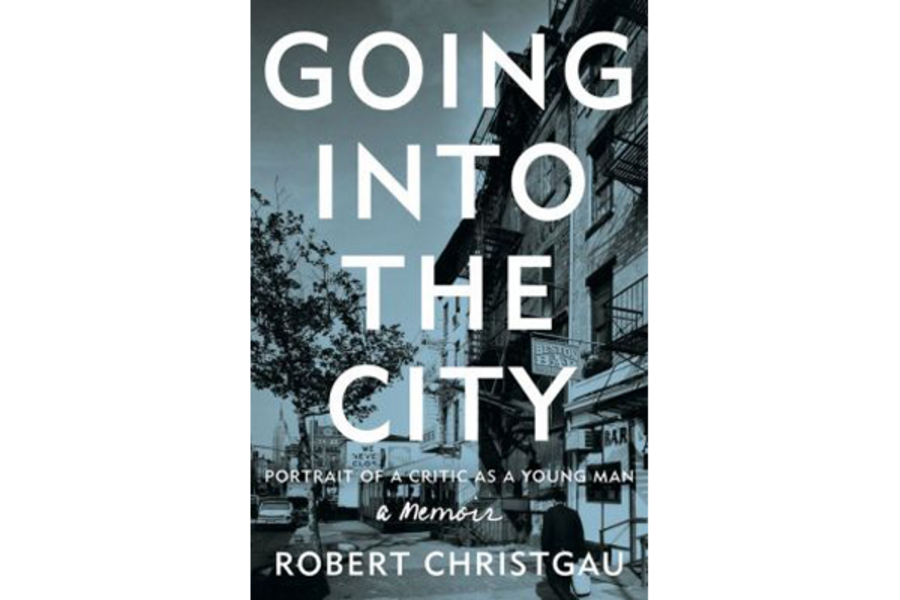

'Going Into the City' tells the story of 'the Dean of American Rock Critics'

Loading...

Robert Christgau’s Going Into the City, a critic’s autobiography, opens with some criticism of autobiography. “Most memoirs fall roughly into four categories,” it begins. This isn’t throat clearing. It’s a signal that the author is disinclined toward novelistic scene setting or woolly emotionalism. Thank goodness – and how strange for a genre that thrives on feelings and pleadings. But then, this kind of interrogation of form has been Christgau’s life’s work: Since the late ’60s he’s been an indefatigable student of, proselytizer for, and turkey shooter of pop music (very widely defined), triangulating records via history, class, race, and his own capacious if prickly tastes.

Former Soul Coughing frontman Mike Doughty once mocked the narrowness of the Dean of American Rock Critics’ life by saying, “Let’s face facts here – what Robert Christgau does is write about his mail.” The response of "Going into the City" is to insist that we’re all reckoning with what’s been dumped on our doorsteps. "Going into the City" is peculiar and remarkable in its unflagging conviction that the disciplined attention a critic applies to art ought to apply to the self as well. Christgau is keenly aware of the hard-to-govern forces – religious, socioeconomic, libidinal – that shaped him, and though the approach has its imperfections, you come away feeling more memoirists should give his strategy a try. Also, it’s funny and has a lot of sex and music in it, though all that gets a serious going-over, too.

Disclosures and admissions: Christgau is a contributor to these pages, and I’m a fan. I have been ever since as a teenager I discovered his ’"80s Record Guide," which I read and reread so often a third of it’s detached from the spine and I’ve memorized some artists’ entries as if it were a hymnal. This likely makes me more forgiving than the average reader for his lengthy disquisitions on how he handled line editing as music editor at the Village Voice. But I’m grateful for anybody who takes care to present criticism as honest labor.

And he’s not going to let you forget that he’s a fireman’s kid. He was born in 1942 into a “just barely lower-middle-class” family in Queens, where a broken arm would keep him out of Vietnam and America’s postwar bounty would facilitate a high-IQ boy’s ability to rise up to an Ivy League school, freelance journalism that paid a living wage, and a leftist bent. A good Presbyterian eager to figure his place in the matrix of God’s creation, he lost his faith at Dartmouth. But the hunger to position himself never diminished: When he writes that his childhood house “wasn’t the nicest house on a tree-lined block where nearly every dwelling was different, but it was the second-nicest on our side,” it’s not a frivolous detail. Place matters, especially if you don’t have God anymore to help you with the job.

Christgau’s story is in many ways a survey of the postwar American institutions that shaped him; the New Critics, Pop Art, New Journalism, daily journalism, alternative journalism, feminism. Music? That, too, though not as much as you might expect. "Going into the City" isn’t a critic’s memoir like Roger Ebert’s "Life Itself" or James Wolcott’s "Lucking Out," powered by the love they expressed for art and writing about it. A closer analogue might be Dalton Conley’s "Honky" (2001), another memoir about a young, bright New Yorker who’s keenly aware of the sociological forces that affect him. Which isn’t to say he approaches people clinically or flatly critically. His depiction of his lengthy relationship with Ellen Willis, the feminist and early New Yorker rock critic whose work is enjoying a welcome revival, is loving and heartbreaking. But he’s also careful to pin down what connected them in the first place: “Coming from Queens is a vaguer bond than coming from near-identical class backgrounds where your father wears a uniform and trades his physical courage for a living wage.”

This left brain/right brain push and pull is in its fullest flower when he writes about his marriage to Carola Dibbell. On one side: sex, kindness, family, “Waterloo Sunset.” On the other: philosophizing about sex, structuring a household, and a few pages of compare-and-contrast between Theodore Dreiser’s "Sister Carrie" and Christina Stead’s "The Man Who Loved Children." A relationship is so important it’s worth thinking about what it means, right? To underscore that point, the two wore matching shirts reading “Monogamy” at their wedding – “in that peculiar subcultural moment, an ideological act.”

Well, Christgau isn’t a novelist, but he knows foreshadowing; "Going into the City" is a story of ideologies and institutions, but also of the way life has of mucking with them. The particular rogue waves that Christgau experienced – his marriage endangered, the Voice on shifting sands – isn’t drama as such. He writes early on that “this is in no way a dysfunctional saga.” But it’s unsettling all the same, and the tone of "Going into the City" reflects the hard-won poise of a writer who fought for the time to figure out where he was positioned. “All lives are interesting – how interesting depends on the telling,” he writes early on. Even Mike Doughty could appreciate that.

Christgau’s calm, clinical mood of self-assessment has room for humor, largely at the expense of other writers: Whacking Norman Mailer, he writes that " ‘jazz is orgasm’ isn’t the stupidest thing he ever said about sex only because it has so much competition.” But he’s often writing at a remove that, if it isn’t quite Olympian, reflects an effort to establish some critical distance. Compare the book’s calm description of one infamously dysfunctional moment – his throwing a piece of pie at his just-ex’ed Ellen Willis – to the infuriated way he put it in 2000, taking a swipe at her “Handy Dandy Theory Generator.” But the trouble with writing about institutions-versus-emotions is that it can be tough to stay in your lane, and occasionally he’ll drift toward fuzzy academese (“My romanticism was both less specific and, I suppose, more essentialist”) or eye-roll-inspiring, Maileresque oversharing about genitalia he has known and loved.

Those guardrail scrapings are surprisingly rare, though, considering the scope of effort. After spending most of a life striving for concision and clarity and detail in the space of Consumer Guide blurbs, he’s mastered the business of getting sentences right. And he’s mindful of the risks; a running theme in the book is what he calls “contingency,” a recognition that life as you know it, in writing, love, or otherwise, has a way of changing on you. "Going into the City" is the story of those inevitable shifts. But Christgau always has one eye on the things that gave him the freedom to consider them – a steady paycheck, a critical theory, his socioeconomic standing. Inanimate objects all, but what can he feel for them but gratitude?