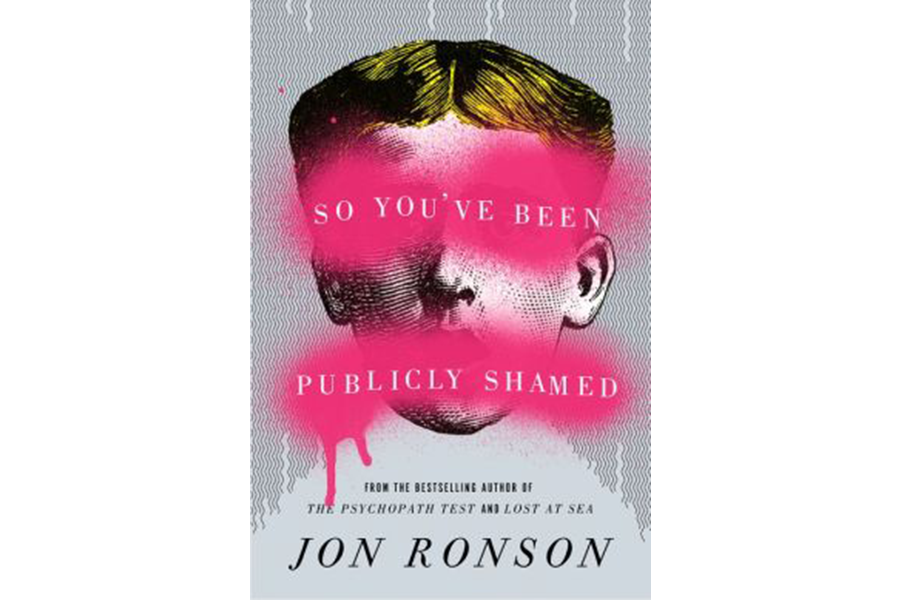

'So You've Been Publicly Shamed' considers today's cruel new forms of public punishment

Loading...

If you’re like many Americans, you read Nathaniel Hawthorne’s "The Scarlet Letter" in high school. Perhaps you visited a living museum like Massachusetts’s Old Sturbridge Village and had your picture taken making a “this sucks” face in the replica pillory – not to be confused with the replica stocks. Ever stopped to wonder why public punishment fell out of use? It isn’t because it lost its effectiveness on an increasingly shameless populace. It’s because, Jon Ronson reveals in So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed, it was deemed “far too brutal.” In 1787, Benjamin Rush went so far as to say that it was “strange that ignominy should ever have been adopted as a milder punishment than death.”

Public punishment has of late been making a pitchfork-waving comeback, and Ronson is alarmed. His book focuses on the Internet’s role in making public shaming popular, easy, and devastating. Tabloid journalism comes in for some scrutiny, but Twitter and Facebook are the true villains in this horror story. Social media’s greatest innovation appears to be the efficiency it lends to the formation of mobs. Some are people whose names you shouldn’t know but whose lives you may have had a small share in destroying: Justine Sacco, “Dongle” Hank, Lindsay Stone. Some attracted the mob’s attention by being well known: the writer Jonah Lehrer, the former Formula One chief Max Mosley, the monologist Mike Daisey, and the former New Jersey governor Jim McGreevey.

The book starts off on somewhat shaky footing, as Ronson recounts – as is more or less de rigueur with this kind of nonfiction – the personal source of his wish to write about shaming. Several years ago, a team of British academics created, for reasons they themselves are helpless to make clear, a Twitter spambot purporting to be Jon Ronson. The bot tweeted innocuously about food. Ronson begged the men to remove it; they refused but agreed to a videotaped debate or confrontation. Ronson uploaded the resulting footage to YouTube, where it garnered comments – aimed at the three academics – that ranged from the merely outraged to the downright violent. “Piss on their corpses,” one suggested.

The academics removed the bot. Ronson didn’t feel guilty for rousing the rabble. He felt “victorious” and “wonderful.” This feeling caused him to revisit the pleasure he’d taken in other mass shamings via social media and to conclude that “we are at the start of a great renaissance of public shaming.” If Ronson’s odd anecdote serves any purpose beyond giving him a plausible personal stake in his subject matter, it is to demonstrate how easy those three academics had it compared to the typical target of online shame campaigns.

Consider the case of Jonah Lehrer. The wunderkind author of books in the Gladwellian pop-sci vein had his life upended when a journalist named Michael Moynihan discovered that Lehrer’s "Imagine: How Creativity Works" contained Bob Dylan quotations that were, alas, imaginary. Ronson interviews both men at length and fleshes out aspects of the story about which the public may never have troubled to wonder. We witness the true extent of Lehrer’s desperation and panic once caught, of course; more surprisingly, we learn of true the extent of Moynihan’s guilt over having wrecked a career. Did his punctilious enforcement of journalistic ethics come at too great a cost?

As with all of the cases discussed in this book, that is ultimately left for the reader to decide. I suspect there are two kinds of writers: the ones who plagiarize and the ones who wouldn’t mind seeing plagiarists dipped in honey and staked to an anthill. Yet it was hard for me, as a member of the latter tribe, not to feel a great rush of sympathy for the humiliated and broken Lehrer – even in the face of his inept apology, which he was paid handsomely ($20,000) to deliver at a conference. Ronson does an admirably judicious job of emphasizing Lehrer’s humanity without excusing his behavior. And, as it happens, Lehrer is one of the least sympathetic people in Ronson’s book.

Justine Sacco and Lindsay Stone had their careers derailed for making tasteless jokes. In Sacco’s case, the joke, about AIDS in Africa, was clearly at the expense of ignorant, apathetic Westerners. Yet the Twitter mob, eager for someone to ruin while feeling self-righteous about it, affected not to know that. Sacco, Twitter said, was a racist. Because Sacco tweeted the joke while boarding a flight to Africa, she wouldn’t find out about the uproar she’d caused until landing many hours later. There was a hashtag: #HasJustineLandedYet. It was like children awaiting Santa Claus, only more childish and infinitely less charming.

Sacco lost her job and told Ronson the experience was “harrowing,” but at least she didn’t receive the threats of violence that Lindsay Stone did. Stone, like Sacco, made a joke whose intent was obvious to those who bothered to look closely but easy enough to misconstrue, deliberately or otherwise. (This sort of thing is catnip for the Angry Internet, which oddly seems to spend more time policing accidental or clueless transgressors – such as college students or the otherwise inexperienced – than the hordes of actual, avowed racists and misogynists the Internet has to offer.) Stone and a friend “had a running joke – taking stupid photographs, ‘smoking in front of a NO SMOKING sign or posing in front of statues, mimicking the pose.’ ” And so Stone’s friend photographed her, flipping the bird and pretending to scream, next to a sign urging SILENCE AND RESPECT at Arlington National Cemetery, and posted the picture to Facebook.

Classy this was not. If only it were needless to say that wishing for Stone to be “RAPED AND STABBED TO DEATH” for a juvenile attempt at humor is a hell of a lot worse. The abuse heaped on Stone hardly honored the men and women she had ostensibly disrespected. What, by the way, was this monster Lindsay Stone doing at Arlington? She and her friend cared for learning-disabled individuals and were leading them on a trip. There was more to Lindsay Stone than her rather limited sense of humor, but the Internet didn’t care to know.

Luckily for her, following a long period of unemployability, she found a job. It was, in fact, her crippling fear of losing it that enabled Ronson to draw her out of her shell; after several of his attempts to contact her were ignored, he enticed her with the promise of the pro bono services of a reputation rehabilitation firm. Ronson’s description of the philosophy and operations of Reputation.com is just one of the fascinating detours the book takes into ancillary issues and figures. Ronson interviews Ted Poe, the congressman who, in his former career as a judge, was notorious for his unusual shaming punishments, and who tells Ronson:

"The justice system in the West has a lot of problems ... but at least there are rules. You have basic rights as the accused. You have your day in court. You don’t have any of those rights when you’re accused on the Internet. And the consequences are worse. It’s worldwide forever.... You [the public] are much more frightening [than I was]. You are much more frightening."

Ronson discusses at length the work of the 19th-century French doctor Gustave LeBon, particularly "The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind." He subjects the Stanford Prison Experiment, patently flawed and a tiresome fixation of people who put too much faith in “studies,” to a novel, bold interpretation. He gets to the bottom of how Max Mosley, accused of participating in Nazi-themed orgies, defied the mob, put a tabloid out of business, and blithely returned his life to, er, normal. In IRL conversation with a dedicated Internet troll, Ronson learns a bit about how the Internet chooses its victims. He endures a ludicrous shame eradication workshop. He finds disgraced former governor Jim McGreevey working in a women’s prison. He visits the headquarters of Kink.com, where he sees things that can’t be unseen.

In other words, although the subject matter of "So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed" is much on everyone’s mind, the book winds up being every bit as surprising and comic as Ronson’s previous excursions into far stranger territory, like "Them: Adventures with Extremists," "The Men Who Stare at Goats," and "The Psychopath Test."

It’s also instructive in ways both subtly thought-provoking and terrifyingly blunt. In one of Ronson’s anecdotes, a woman shames a man for something trivial, gets him fired, and is shamed for that – which leads to her firing. A similar story is trending on the Internet right now: A man shamed a random Chick-Fil-A employee for tacitly supporting homophobia; he was shamed for shaming her; he lost his $200,000-a-year job and lives in an RV with his family. Shame, like a nuclear weapon, is a powerful deterrent. But nobody can come to an agreement about who should wield it – so, as it stands, all it’s likely to deter are honesty and free expression.