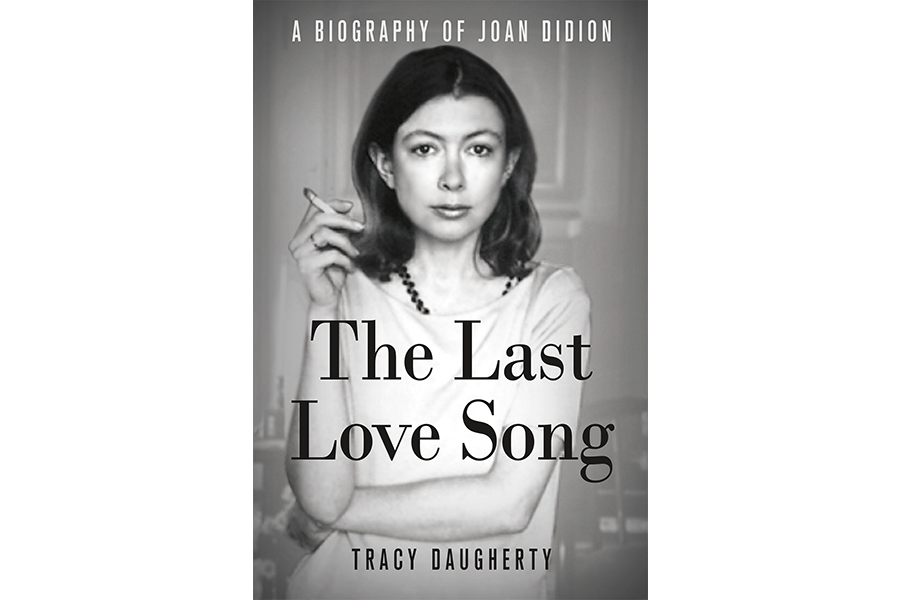

'The Last Love Song' offers a sympathetic, insightful look at the life of Joan Didion

Loading...

In the summer of 2013, at age 78, Joan Didion was a recipient of a National Humanities Medal. The setting was the White House, and in his remarks about the author of “Play It As It Lays” and “The Year of Magical Thinking,” President Obama emphasized that it was past time for her to receive the honor. “I’m surprised,” he said, “she hasn’t already gotten this award.”

Yet one wonders whether Didion let herself be swept up in the occasion – and, after reading Tracy Daugherty’s magisterial, extraordinarily sympathetic new biography, The Last Love Song, one suspects not.

As Daugherty notes, Didion expressed skepticism about the president – as she had about his predecessors, including Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. In a sharp essay, published shortly after the 2008 election, Didion complained of “the spirit of a cargo cult” that had accompanied Obama’s ascent. “Close to the heart of the problem was the way in which only the very young were decreed capable of truly appreciating the candidate,” she wrote, clearly rankled by the peer pressure to get on board.

Never was there a writer more constitutionally incapable of being a team player than Joan Didion. The perspectives she proffers, whether on feminism or John Wayne, are usually askance, rendering her – in the astute words of New York Review of Books editor Robert Silvers – “by no means predictable, by no means an easily classifiable liberal or conservative.”

Of course, Didion has very real leanings. Early in the book, the Sacramento native is quoted as writing that she grew up in the company of (and was thus influenced by) “conservative California Republicans,” and she is later said to have journeyed to her home state from New York to cast a vote for 1962 Republican primary contender for governor Joe Shell – “Nixon,” Daugherty writes, “was too liberal for her.” The big-picture point, however, is that Didion regularly runs afoul of fleeting fashions, especially in the essays gathered in such books as “Slouching Towards Bethlehem” and “The White Album.”

While matriculating at University of California, Berkeley, she had no regard for the anti-establishment happenings on campus, as Daugherty writes: “The Beats, the avant-gardists, the Berkeley Gothics with their stream-of-consciousness ‘poetry,’ their orgies, yoga, and chemical enhancers – Didion couldn’t stand them.” And, following a “guest editor” tour of duty at Mademoiselle, she was already serious about her craft, and immune to guff.

“For Didion, writing was not a matter of communing with the spirit of the forest, sparking revolution, or buzzing with Eros,” Daugherty writes. “It was deadlines, cut-and-paste jobs, pleasing Saks Fifth Avenue.”

A contest led to employment at Vogue, but novel-writing beckoned, as did contributions to National Review. “In its pages, mostly in book reviews, she expressed her dismay at the straying of the nation and perfected the tone of lament that would center her first novel,” Daugherty writes, referring to “Run River.”

She was bewitched by Barry Goldwater, Daugherty writes, because he recognized, as did she, that what ailed the human race resisted being “solved by political action”: “He never would have tried to regulate the world into a happier place.” And, of course, The Duke was a hero worth worshiping. “In John Wayne’s world, John Wayne was supposed to give the orders,” Didion writes of his authoritative appeal in an appreciative essay for the Saturday Evening Post. “‘Let’s ride,’ he said, and ‘Saddle up.’”

In her enduring marriage to writer John Gregory Dunne (they joined forces on several brilliant screenplays, including “The Panic in Needle Park,” expertly detailed here), followed by the adoption of daughter Quintana, one can see the source of Didion’s indignation over the rise of the hippies in the title essay in “Slouching Towards Bethlehem”: “These were the children who grew up cut loose from the web of cousins and great-aunts and family doctors and lifelong neighbors who had traditionally suggested and enforced the society’s values.”

In other words, family matters for Didion – another unfashionable angle, and one reinforced a hundredfold, decades later in “The Year of Magical Thinking” and “Blue Nights,” concerning the despondency of a family gone missing, when Dunne and Quintana died, respectively, in 2003 and 2005. “To announce Dunne’s death publicly in an obituary would be to officially sanction and ensure his death, thus barring him from returning,” Daugherty writes, summarizing the “magical thinking” of the earlier book.

For one who has struck out on her own so often, it is unsurprising that Didion declined to cooperate with Daugherty. Her refusal may have been a blessing in disguise: as if compensating for her lack of participation, Daugherty practically establishes a psychic connection with Didion, as when he offers better than an educated guess about Didion’s uncredited authorship of a “People Are Talking About” column in Vogue, suggesting “it’s clearly Joan Didion on the streets of Reno observing ‘ranchers’ sons in Brooks Brothers suits and Stetsons.... everyone speaking in the Oklahoma drawl, now the accent of the far West.’” Every aspect of Didion’s life and work is pondered thoughtfully.

Indeed, this doorstop of a book – telling not only of Didion, but of Dunne and Quintana, and the East and West coasts on which they made their homes – is made manageable because, as a reviewer in Publishers Weekly noted, Daugherty tends to “mimic Didion’s own famously cool and elliptical style.”

Imitation it may be, but the book is fleeter for it, and so persuasive is Daugherty’s argument on behalf of his subject that one laments the likelihood that “Blue Nights” may be among her final works (included is a litany of recent, never-realized projects). The atypical analyses of Joan Didion will forever be welcome.

Peter Tonguette has written for The Wall Street Journal, The Weekly Standard, National Review, and many other publications.

# # #