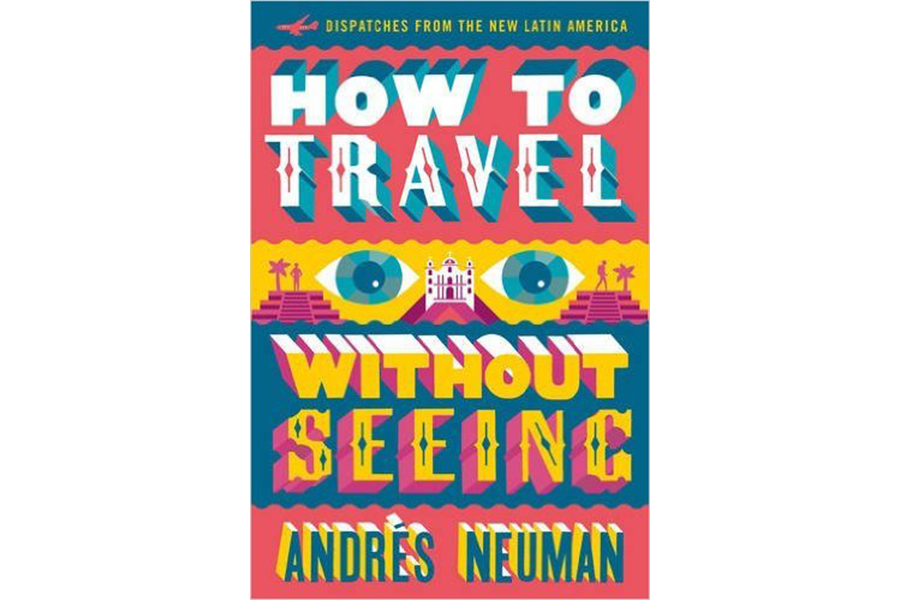

'How to Travel Without Seeing' takes readers on a book tour of Latin America

Loading...

“Perhaps the greatest travel book, the most unpredictable of all,” Andrés Neuman suggests in the closing paragraphs of How to Travel Without Seeing: Dispatches from the New Latin America, “would be written by someone who doesn’t go anywhere and simply imagines possible movements. Facing a window that seems like a platform, the author would lift his head and feel the rush of the horizon.”

It’s a line that operates as both valedictory and epigraph. "How to Travel Without Seeing," after all, is a travel book by an author who is ambivalent about travel ... or, at least, about travel’s theoretical rewards. “These days,” he insists, “we go places without moving. Sedentary nomads, we can learn about a place and travel there in an instant. Nevertheless, or perhaps consequently, we stay at home, rooted in front of the screen.”

If this sounds like a contradiction, that’s part of the point. This elusive travelogue offers an epigrammatic record of Neuman’s 2009 book tour of Latin America, beginning in Buenos Aires, where he was born and lived until he was 14, when his family moved to Spain. The intent is to craft a record of disruption, to frame travel not as connective so much as the other way around. “I deal with the trauma of displacement through writing,” Neuman told The New York Times in 2014, shortly after his novel "Talking to Ourselves" appeared in English. That book, too, opens with a journey, although it is a journey of a very different sort. “Each novel,” he has said, “should refute the previous one” — which explains the shifts from book to book. And yet, this also provokes (for American readers, anyway) one more layer of dislocation, since of Neuman’s 18 books, only four have been published in the United States.

Such fragmentation highlights one of the challenges of literature in translation: We can only read what is available to us. And yet, in Neuman’s work, that is almost paradoxically the point. "Traveler of the Century," the first book of his to be translated into English, is a 600-plus-page picaresque, unfolding along the boundary of Saxony and Prussia, in an imagined Europe that blends history and allegory.

"The Things We Don’t Do" gathers 34 stories, many of them microfictions, including four “bonus tracks,” or dodecalogues, which string together a series of aphorisms in an extended commentary on the storyteller’s art. “The extreme freedom of a book of short stories,” he writes there, “derives from the possibility of starting from zero each time. To demand unity from it is like padlocking the laboratory.”

A similar argument might be made about all his books. "Talking to Ourselves" is a prime example, a novel so riveting that no sooner had I finished than I started reading it again. Comprising three alternating first-person narratives — a 10-year-old boy, his terminally ill father, and his mother, who plays her mourning out by way of sexual conflagration — it describes a family unraveling, one misunderstanding or betrayal at a time. For Neuman, though, the only betrayals that matter are those we visit upon ourselves. “From then on,” the mother tells us, in the wake of her first dalliance, “everything that happened, how can I put it? acted like an antidote. Every word, every gesture conspired to block my path and prevent my escape.” She is referring both to the relationship and to her family: a situation in which there are no rules, no codes of behavior, just a set of specific circumstances that determine their response.

What Neuman is after is to play with our expectations, as well as his own. His work is constantly creating its own vernacular. Certainly, that’s the case with "How to Travel Without Seeing," which makes a point of sticking to the surfaces. “[E]verything is possible because nothing happens,” he writes, articulating such a point-of-view. The idea, in other words, is to deconstruct what it means to travel — not to immerse in other landscapes so much as to express the self as it moves through these places, by turns alien and contained.

Thus, even as we follow Neuman from Argentina to Uruguay to Chile, Peru to Ecuador to Venezuela, what we learn about these locations is glancing, indirect. In La Paz, he discovers a poem graffitied by the feminist collective Mujeres Creando: “After making your dinner / and making your bed / I lost the desire / to make love to you.” In Guatemala City, he comes across the Kafka bar, named, a waitress tells him, for “a Swedish writer the owner likes a lot.” The ironies and inconsistencies only heighten the experience, for in a globalized world, everything is up for grabs. Neuman quotes the Argentine poet Santiago Sylvester:, “Whatever is not a window is a mirror.” The statement is worth keeping in mind. As 'How to Travel Without Seeing' progresses, it increasingly functions on these terms, as a set of vignettes, reflections, shards of memory or observation that add up in the only way such fragments can, as an approximation of consciousness.

That such consciousness is discontinuous goes without saying; the world through which Neuman moves is an unapologetically postmodern one. Even our definitions are open to conjecture, an idea he makes explicit by including Miami and San Juan, Puerto Rico, in his travelogue. Still, the question this raises is not whether these cities are part of Latin America but rather whether all of it, Neuman’s whole itinerary, illuminates a broader notion of the Americas, in which the border is first and foremost a psychological, or an emotional, dividing line. “To travel the world today,” he writes from Lima, “is to witness the same debates in different languages and dialects.” It’s an impression that echoes throughout the book.

In San Juan, the Spanish-speaking capital of an unincorporated U.S. territory, he riffs on the evolution of language: “Puerto Rican bilingualism sometimes works like Google Translate, copying words and syntactic structures from English. When I arrive, they announce that the airport is under construction — bajo construcción rather than en obra. In the hotel, they explain to me that Wi-Fi is complimentary — complementario rather than gratis.... The Spanish they speak here is simultaneously familiar and strange, under construction and complimentary. If the language needs something, it takes it. And it no longer knows where it’s coming from.” Neuman is describing a condition all of us recognize, that odd feeling of statelessness bestowed by contemporary travel, in which “movement itself was the last of our concerns.”

Late in the book, while flying from El Salvador to Costa Rica, he offers a telling anecdote. “From the window of the plane,” he recalls, “I see the dark green squares of the fields, the blue dent of a lake among the folds of the mountain range. With a mixture of knowingness and emotion, I think: It looks like Google Earth! This is the way things are. This is the way our eyes work. Birds-eye images on screens don’t evoke the feeling of being on planes. For us, it’s the reverse: planes are like screens.”

I love, I have to say, that exclamation point, its breath of recognition, even (or especially) if the recognition is generic and belongs to everyone. This is what it means to travel now, Neuman tells us, not the shock of the new but of the familiar, the ways in which identity blends. The book was written in 2009, but it’s impossible to read without reflecting on current realities; what does all this mean beneath the shadow of a border wall? Neuman doesn’t shy away from such complexities; "How to Travel Without Seeing" is full of references to the politics and culture of the countries he visits, although the most ubiquitous signifiers are the effects of a region-wide flu epidemic and the death of Michael Jackson, which occurs as Neuman embarks. In any case, his offhand, aphoristic structure flattens out reaction, rendering each impression as just another momentary idea. What ties them together is that nothing ties them together — there is no master narrative. There is only the self, moving through a world of mass migration and entertainments, inauthentic and authentic at the same time, as travel always is.

In the end, that makes "How to Travel Without Seeing" less a book about travel than about boundaries, a succession of airports and border guards. The experiences it describes are liminal, occupying the interstices between departing and arriving, being there and being gone. “Before I leave,” Neuman writes, “a friend tells me, ‘If you publish the notes you’re writing, at some point you’ll have to present them in every city that appears in the book.’ ” Double image, double mirror. The tension sits at the center of Neuman’s work. “I imagine myself,” he continues, “presenting the book in every place that appears in it and writing, at the same time, a journal about that second trip, which could be presented again, city by city, and so on to infinity. Once you start on a journey you can never quite end it.”