Newbery, Caldecott winners: Jack Gantos, Chris Raschka take the top prizes

Loading...

If there’s one thing this year’s Newbery and Caldecott winners taught us, it’s a confirmation of the old adage, “write what you know.” This year’s winners scored accolades putting mundane personal experiences to paper, from growing up in a town created by the Depression to witnessing a dog lose a favorite ball.

Jack Gantos won the Newbery Medal, awarded for best children’s literature, for his semi-autobiographical novel, “Dead End in Norvelt.” The story hits very close to home for Gantos, to say the least. Set in 1962, it follows the hilariously improbable adventures of a boy named Jack Gantos growing up in Gantos’ former hometown, Norvelt, Penn., created by the federal government during the Great Depression.

The ALA described it as “an achingly funny romp through a dingy New Deal town.”

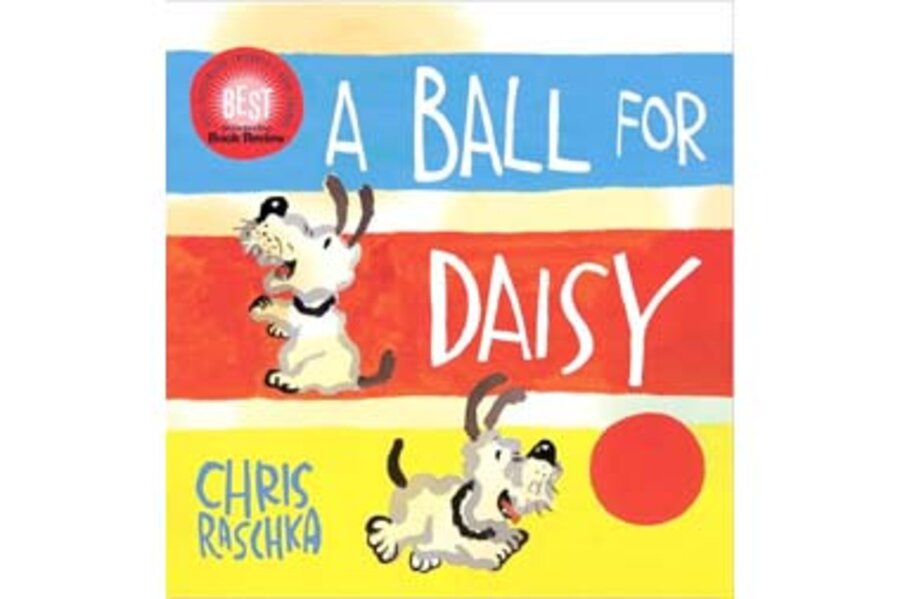

Chris Raschka, who won the Caldecott Medal, awarded for best picture book, also stayed close to home with his picture book, “A Ball for Daisy.” The wordless book for ages 3 and up deals with a dog’s loss of her favorite ball. It was inspired by an everyday incident in an elevator a decade ago involving Raschka’s four-year-old son, his favorite ball, and a dog named Daisy. The dog eventually destroyed the ball, but it also sparked the idea behind the award-winning book.

“My son eventually got over it,” Raschka told USA Today, “but I thought it’d make a good picture book.” The challenging part he said, was “achieving the right balance between empathetic response without making it too upsetting for kids.”

“Dead End Norvelt” also drew directly from Gantos’ experience. He was at a funeral eulogizing his aunt in the real Norvelt, Penn., when he discovered how little Norvelt’s residents knew about the town’s roots as a federal project created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt and named after a combination of the last syllable’s of Eleanor Roosevelt’s name: EleaNOR RooseVELT. Gantos said he was shocked at how little the town knew about its history and determined to share his hometown’s history through a children’s book.

At the awards ceremony, hosted by the American Library Association in Dallas, Gantos said he wanted to “bring history alive, not treat it as an object behind glass, collecting dust.”

If there’s one more thing this year’s awards taught us, it’s that there are second acts in life. At 20, Gantos spent 18 months in prison for drug running. “When I got out,” he said, “I had a lot of focus. I never wanted to do that again.” His 2002 memoir for teens, “Hole in my Head,” describes what he calls the “bleakest year of my life.” Today Gantos has 45 books under his belt, including a Newbery Honor, a Printz Honor, and a National Book Award finalist designation.

Raschka’s first act was as a violist and member of the orchestras in Ann Arbor and Flint, Michigan, who turned to art and illustration full-time only after tendinitis ended his musical career. Today, Raschka has written or illustrated about 50 books, including the 2006 Caldecott winner, “The Hello, Good-bye Window.”

With this year’s awards, Gantos and Raschka proved that success can be as attainable as second acts writing what they know.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.