Heinrich Barth: the greatest explorer you've never heard of

Loading...

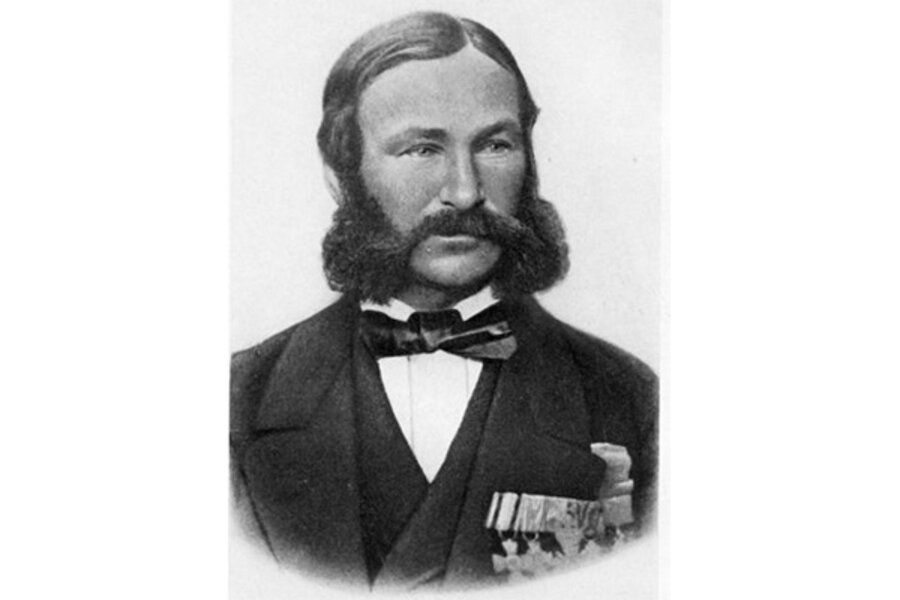

His fantastic mutton chops alone should give Heinrich Barth some immortal fame. But that's not all that sets him apart. The 19th-century German explorer led an extraordinary five-year expedition into Islamic Africa, a journey that taught the West about the amazing cultures and creatures of a mystery continent.

But Barth and his adventure are barely remembered today. Perhaps it's because of his nationality, his prickly personality, or his inability to express his thoughts in anything less than thousands of pages.

Whatever the case, one of the world's great explorers is now the subject of his first biography in English. It's titled "A Labyrinth of Kingdoms: 10,000 Miles through Islamic Africa" and written by Connecticut-based freelance journalist Steve Kemper.

I reached Kemper at his home and listened to his soft Kentucky accent – he's from Louisville – as he described an explorer worth remembering for more than his sideburns.

Q: Why haven't we heard of this guy?

A: There are a lot of reasons, and they all add up to a perfect storm.

He was German and working for the British, who like their heroes home-grown and have a long history of suspicion of the Germans. He managed to accomplish one of their greatest expeditions ever, and he was German. Some people didn't get over that.

There was also was the length and density of Barth’s work -- 3,500 pages of closely observed nature, culture, ethnography. The book didn't create the stir that Livingstone and Stanley did.

Then there's the stuff he came back with: Islam is a great religion, and Africa has a history of culture and literature, complex societies and systems of government. This was going against what people wanted to believe about the continent they wanted to pillage and take over.

And there was also his personality.

Q: To borrow an old word, he seems like a bit of a prig. Was he?

A: Not more priggish than other Victorians were, but he was highly susceptible to slights against his honor. Whenever he felt he was slighted, he responded with too much pique.

When he left Britain and went back to Germany, all those things added up to him being neglected.

Q: What did he discover during his travels in north-central Africa?

A: He discovered the Benue River, the major tributary of the Niger River, and he discovered a couple of kingdoms that were totally unknown. He went to a lot of places that nobody knew about.

Q: As you write, he spent time in Timbuktu, which still has a reputation as being a place out in the boonies. What's the story behind Timbuktu?

A: It's had a reputation for centuries.

There was an man named Mansa Musa, the emperor of Mali, a gigantic kingdom in Africa in the 14th century. He decided to make a voyage to Mecca, and took camels laden with gold. When he got to Cairo, he spent like a crazy man and his hajj became legendary. That’s when people first heard of Timbuktu, thinking there must be a golden city there.

It was a mythic place in most people's minds. But Barth was a scientist, so he wasn't interested in the myth. He was interested in the data. He brought out so much information about what was in the market, how much things cost, what the system of government was like, who was in power.

He spent his seven months there essentially under house arrest. But he did make a number of outings under threat of death and brought back a picture of the educated people and uneducated people, and the fundamentalists and the scholars, which sounds so familiar today.

Barth said Timbuktu was a very literary place, filled with manuscripts. That was a pretty shocking idea in Europe.

Q: What did he learn about Islam?

A: Almost anything he understood was not understood in the West because we're so ignorant of Islam.

He brought back information that you could find scholars in Africa -- Islamic scholars who could you talk to you about astronomy, Aristotle, Ptolemy, music, law, theology.

He brought information about all the factions of Islam and the fanatical sects. He said it is a great religion that is controlled in some areas by fanatics and ignorant people, and it has never lived up to his potential. And by the way, neither has Christianity.

Q: Did he make a big point of that observation?

A: He made a couple quips about that, reminded people that Christianity had done some of the same things that the West had accused Islam of doing. What he said was that Islam is like any other religion: It includes great people, it includes criminals and thugs and ignorant people, and both shysters and magnificence. It's a great religion, it deserves respect.

He could quote the Koran, especially the opening prayer, which saved his life several times.

Q: Do you feel like you're restoring his reputation?

A: I really hope that this brings him to people's attention. Boy, he deserves it. He's one of the greatest explorers who ever lived. Why he's not known is a mystery and a shame, and I hope my book does a little bit to nudge him back toward the spotlight.

Q: Why is his story important today?

A: You can't help but read his story and this book without noticing how ignorant Europe was about Africa – and how ignorant we still are.

Barth had a totally idealistic view about the ability of science to dispel ignorance. I hope my book adds one little match to that flame.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.