Democratic National Convention: a wild ride in 1924

Loading...

Almost nine decades ago, the Democrats got together in New York City and tore themselves apart.

They fought over civil rights and the Ku Klux Klan. They fought over religion. They fought over legalizing liquor. And they did it for more than two whole weeks while botching everything from the music to the celebratory fire sirens.

The Democratic National Convention of 1924 remains the most destructive of all time. "During its 16 days and 103 ballots, the party virtually committed suicide," writes historian Robert K. Murray.

The players included a future president who'd lose that November, a Catholic governor, a KKK sympathizer and the ultimate nominee, a man who described the chaos, in a bit of understatement, as "a three-ring circus with two stages and a few trapeze acts."

The best and most deliciously readable account of the Mammoth Mess at Madison Square Garden appears in Murray's 1976 book The 103rd Ballot. As the Democrats anoint their nominee in Charlotte tonight, here's a look back at the ultimate height of conventional dysfunction, courtesy of a master historian:

Hey! Let's Insult the South, Part I: When a favorite son from Virginia was nominated, the convention band struck up an awkward selection: "John Brown's Body Lies A-Mouldering in the Grave," a favorite of the North during the Civil War.

It was not, as you can imagine, a chart-topper in the Old Dominion. The band quickly changed its tune, literally, to "Carry Me Back to Old Virginny."

Hey! Let's Insult the South, Part II: Later, during a discussion about the KKK, the band played "an ancient hymn of hate" of the Union Army called "Marching Through Georgia." This "monumental gaffe" infuriated the Southern delegates, who were less than pleased to be reminded of the work of General Sherman.

The Sound of Flee-Dom: After a man named Franklin Delano Roosevelt urged his fellow Democrats to support Al Smith, the New York governor, the "Garden turned into a cauldron of sound and movement."

That's not unusual at a political convention. But this was: a man had hired a bunch of people to turn on battery-powered fire sirens, which turned out to be an extremely bad idea. The noise was so sharp and loud that "men and women sitting in front of these machines were blown out of their seats and staggered around shell-shocked. Children in the audience screamed with fright."

The sirens blared for more than 30 minutes. A radio announcer was so disturbed by the din that he told listeners he worried the hall's skylights would fall in.

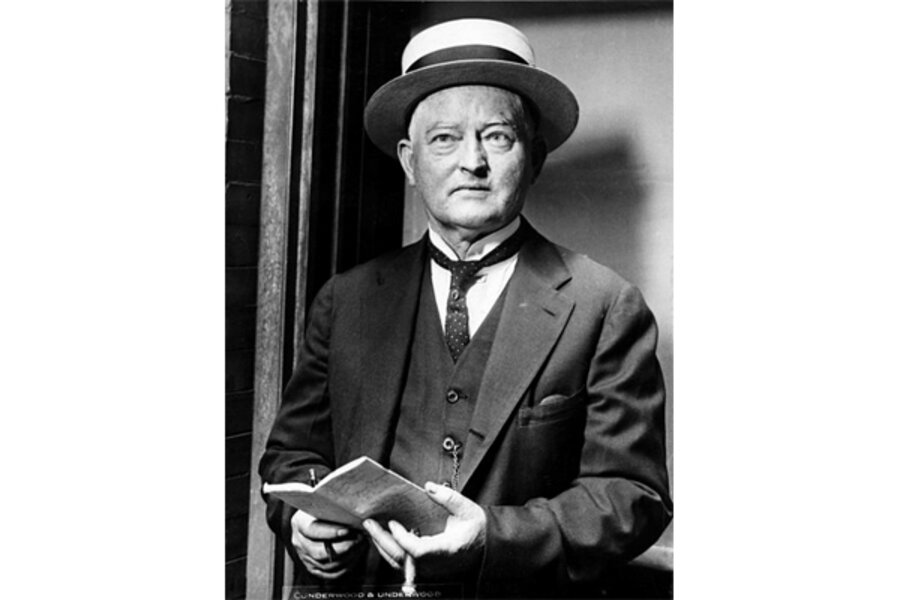

Tangled Up over Racism: One top hopeful, former secretary of the treasury and Californian who had the unlikely name of William Gibbs McAdoo, played footsie with the Ku Klux Klan and even got support from it. He didn't turn it down because he wanted the South's support.

That wasn't all. The delegates actually debated the KKK, even though nobody actually wanted to come near the issue. This did not go well: "No paradise of human understanding at best, Madison Square Garden now turned into a pit of crouching hates and simmering prejudices."

The vicious KKK debate finally ended in a chaotic two-hour vote that produced the most "prolonged pandemonium in an American political gathering."

"The delegates engaged in fist fights, arguments, name calling, wrestling matches, and brawls, while the galleries howled and stomped their feet." The fighting veered toward a riot that was only averted when 1,000 NYC cops hurried to the scene.

Sit Back, Stay a While: The balloting to choose the nominee went on. And on. And on. Will Rogers complained, as Murray put it, "that New York had invited the delegates as visitors, not to live there."

One day featured a whopping 19 ballots, the most ever taken on a single day of a major political convention in U.S. history.

Meanwhile, on Independence Day, 20,000 Klansmen and their families met to rally in nearby New Jersey. They built an effigy of Smith, the Catholic governor, and smashed it with baseballs at a nickel for three throws.

This Was No Magic Number: Finally, after 102 ballots, just two candidates remained in the running. One was "an eastern Wall Street lawyer" from West Virginia. The other was, of all things, a "wet anti-Klan southerner."

The lawyer, John W. Davis, got the nomination on the 103rd ballot. He was a compromise and, ultimately, a loser. The incumbent, Calvin Coolidge, would be elected president with 54 percent of the vote. Davis couldn't even reach 30 percent.

Davis would eventually abandon his party and embrace the GOP.

Smith, the New York governor, would try for the nomination again in 1928 and get it. But Herbert Hoover would wipe the floor with him.

And FDR? He'd run, and lose, on the 1924 ticket with Davis as a vice presidential candidate. He'd roar back, older and wiser, eight years later and win the White House.

So why bother reading about 1924? It turns out that there's more here than a few amusing and appalling tales. The havoc at the convention represents the era's battle over who gets to enjoy the full benefits of being an American.

"(E)very shade of opinion, every prejudice, every fear, every division which could be found in American society as a whole was duplicated in Madison Square Garden in 1924...," Murray writes. "Marking the first concerted attempt to reach a political consensus on many of these matters, the Garden convention was a failure."

Still, the convention and its aftermath "provided eloquent testimony to the tenacious belief of the American public in the efficacy of the democratic process and to the Democratic party's persistent search for a workable political consensus."

The Democratic party, strong enough to survive this epic prize fight in Madison Square Garden, would stick around for another 88 years (and counting). And American democracy, no delicate flower, would keep on thriving.

Randy Dotinga is a Monitor contributor.