Should authors allow their books to be censored for publication in China?

Loading...

To censor or not to sell?

For authors trying to sell their books in China, that is the question.

According to a recent piece in The New York Times, authors attempting to access the massive audience in China are increasingly facing a difficult decision: To allow their books to be censored for sale there, or not to sell there at all.

“Many writers say they are torn by their desire to protect their work and the need to make a living in an era of shrinking advances,” writes the Times. “For others, it is simply about cultivating an audience in the world’s most populous country, a rising superpower that cannot be summarily ignored.”

Ezra F. Vogel, whose biography of Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping was published in China after passing through censors, put it this way:

“To me the choice was easy,” he told the paper. “I thought it was better to have 90 of the book available here than zero.”

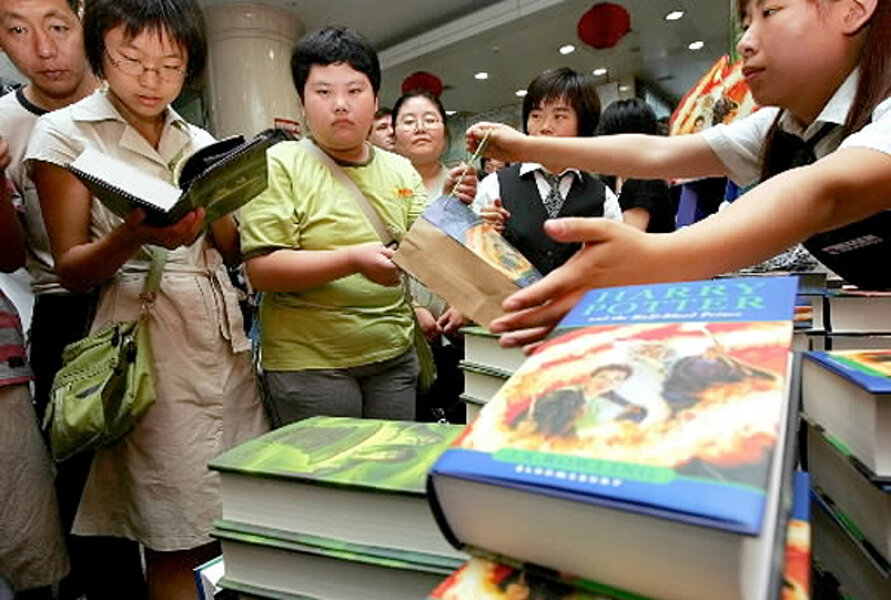

What’s behind this “deal with the devil”? Thanks to a huge and highly literate readership hungry for foreign books, China is becoming an increasingly lucrative market for American authors and publishers. Consider this: Chinese publishers bought 1,664 titles from abroad in 1995, according to the NYT; in 2012, they bought more than 16,000.

More compelling figures: e-book earnings alone for American publishers also grew 56 percent in China last year, according to the Association of American Publishers. Popular authors can do especially well. J.K. Rowling took in $2.4 million in royalties in China alone last year. Walter Isaacson, author of the Steve Jobs biography, earned $804,000.

Typically off-limits are books that mention ethnic tensions, Taiwan, the banned spiritual movement Falun Gong, and even passing references to the Cultural Revolution or to contemporary Chinese leaders.

“…authors of sexually explicit works or those that touch on Chinese politics and history can find themselves in an Orwellian embrace with a censorship apparatus that has little patience for the niceties of literary or academic integrity,” writes the Times.

This isn’t the first time China has made headlines for its policy on foreign books and publishing.

In 2012, a territorial dispute between China and Japan escalated into a book battle in which Chinese authorities asked booksellers in Beijing to ban books by Japanese authors and titles about Japanese topics, including the Haruki Murakami’s bestselling ‘1Q84.’

This time, China isn’t looking to ban books – simply censor them. And thanks to a hugely lucrative market, it seems in most cases, authors and publishers are willing to play along.

Husna Haq is a Monitor correspondent.