What I didn't know about Tiananmen Square

Loading...

As a reporter I covered the Beijing massacre of 1989 and then studied the issue for years afterward. I was beginning to think that I had nothing more to learn about it.

But Rowena Xiaoqing He’s new book "Tiananmen Exiles" has given me fresh insights and an appreciation for the challenges that exiled Chinese student leaders faced after they escaped from China.

Twenty-five years after the Chinese Army opened fire on student-led pro-democracy protesters, I still have much to learn.

Through oral history, Dr. He tells the story of three student leaders who suffered through prison and then exile. They describe in their own words what inspired them from an early age and then how they struggled in later years simply to make a life for themselves.

But equally compelling is He’s own story as well as that of a Hong Kong student who witnessed terrifying acts of brutality directed at unarmed Beijing civilians during the period from June 3 to June 4.

Upon graduation from a university in China, He moved from jobs at two state banks to work for two international financial institutions. Friends were shocked when she gave up a good salary to go into exile in Canada, where she went on to earn her doctoral degree.

Because she herself had witnessed the 1989 events from southern China and then went through the humiliation of being told by her teachers to lie about what happened, finally studying the issues for years, she was well-positioned to do the research and write this book.

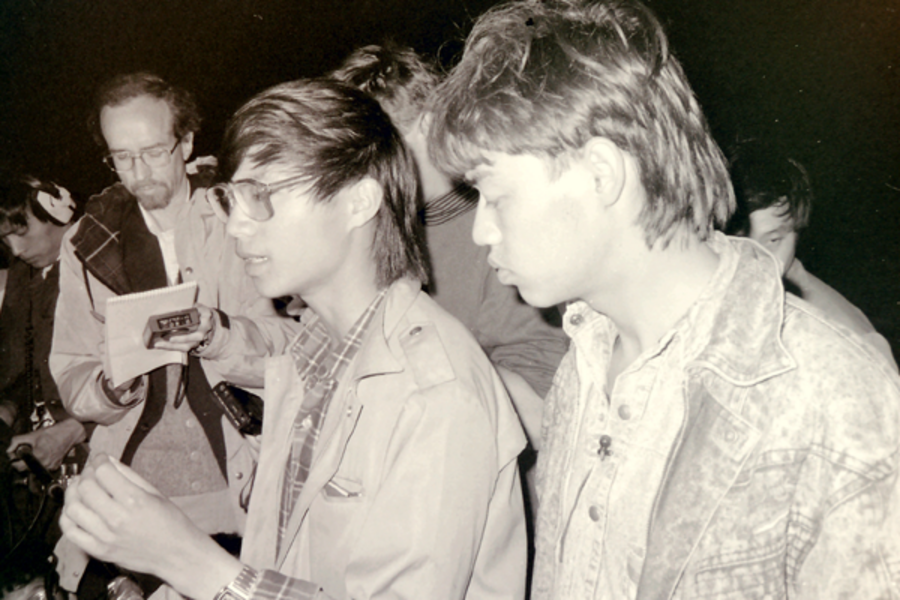

I should declare an interest here. I’ve known two of the student leaders featured in the book for many years. One of them, Wang Dan, serves as a commentator for the radio station I work for, Radio Free Asia. A third student leader worked more than a decade ago for RFA’s Cantonese service for three years.

Also, in the spring of this year I participated in a panel discussion on Tiananmen press coverage as part of a conference at Harvard University organized by Rowena He. Today she teaches as a lecturer at Harvard, where she has for several years organized student seminars on the Tiananmen pro-democracy movement of 1989.

'Patriotic education'

As Professor Perry Link, an expert on Chinese language and literature, notes in the prologue to the book, within weeks of the killings in Beijing, China’s supreme leader Deng Xiaoping had declared that what China needed was “patriotic education.” This, he indicated, would counter the impression that the Communist Party had now lost its legitimacy. Its new bases of legitimacy would now be nationalism and money making.

Deng essentially told the Chinese people that they could go all-out to get rich but should remain silent when it came to “sensitive” topics such as Tiananmen. Any discussion of the massacre in Beijing became taboo.

Chinese students who attend Rowena He’s seminars are often hearing for the first time what really happened in Beijing in 1989 as opposed to the official line, which is that a “political disturbance” or “incident” had occurred in that year.

Given the corruption at all levels of government that has engulfed China over the past two decades, Dr. He’s book serves as a reminder that a generation of Chinese students once opposed corruption and embraced an idealism that demanded accountability from the government.

The most-wanted list

Ironically, many of those students were first inspired by communist ideals, among them Wang Dan, a student leader who found himself at the top of the government’s most-wanted list after the crackdown in June 1989.

As Wang himself explains in "Tiananmen Exiles," his mother was a professor who specialized in the history of the Chinese Communist Party. As a child, Wang enjoyed reading about the Party’s heroes. He believed in Marxism. He wanted to serve the Chinese people.

“I think that 1989 … brought out the best parts in the human nature of the Chinese people,” says Wang. But he adds that in today’s China, people have learned subconsciously that they must lie and that they do this without even realizing it.

Shen Tong, another student leader that I got to know only after the crackdown and when he was in exile, relates in the book that his early thinking and values were influenced by Western literature and culture. His later political activism, he says, was inspired by reading about Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

Yi Danxuan, a leader of student protests in southern China, was not known to most of us. As Beijing bureau chief for The Washington Post in 1989, I was unaware of him. That’s because major events were occurring nearly every day in Beijing, making it difficult to get out of the capital and to witness a pro-democracy movement that had spread to cities and towns throughout China.

As Rowena He explains, Yi’s experiences as a student leader in Guangzhou “offer a useful counterpoint to the better-known stories of Wang Dan and ShenTong.” His experiences “seem closer to the reality of many other members of the exiled dissident community.” Dissidents like Yi “suffered imprisonment and exile like their more famous counterparts, enduring those hardships in anonymity and obscurity.”

Impact on families

At the same time, parents and other relatives suffered because of their association with the three student leaders.

Wang Dan’s mother, a professor at one of the most prestigious universities in China, was sent to prison. Shen Tong’s father, a Beijing municipal government employee, came under pressure to spy on his son’s pro-democracy activities. He declined to do so and suffered for it.

In 2009, the Chinese authorities denied Li Danxuan a visa to return to China to see his father, who was diagnosed with cancer.

The three student leaders pursued different paths in life once they reached the United States.

Wang Dan got a Ph.D. in history, teaches in Taiwan, and continues to speak out and write about China and Tiananmen.

Shen Tong started his own software company and became a successful businessman. He suffered from nightmares for many years but those ceased when he married and became a father. He lives in New York City.

Yi Danxuan continues his activism but says little about it for fear of endangering those who are in touch with him in China. He lives in Washington, D.C.

Marginalized and demonized

Rowen He argues that the student leaders from 1989 have been marginalized and demonized. The post-Tiananmen generation has grown up learning “a state-approved history in an environment of intensifying nationalism.” Many consider critics of the regime to be “national traitors.”

Have nationalism and money making totally triumphed over idealism? If this were the case, how can one explain the growing number of religious believers in China?

Rowena He herself is an example of someone who has battled for years, sometimes in the face of angry criticism, to keep alive the memories of an idealism that emerged in full force in 1989. And she’s determined not to let us forget.

Dan Southerland, executive editor of Radio Free Asia, is a former Monitor correspondent and a former Beijing bureau chief for The Washington Post.