Spring cleaning: Can you narrow your book collection down to 30 titles?

Loading...

Today is the first day of April, when thoughts turn to spring cleaning. For book lovers, it’s an especially good time to weed one’s personal library, clearing the shelves of titles not likely to be read again.

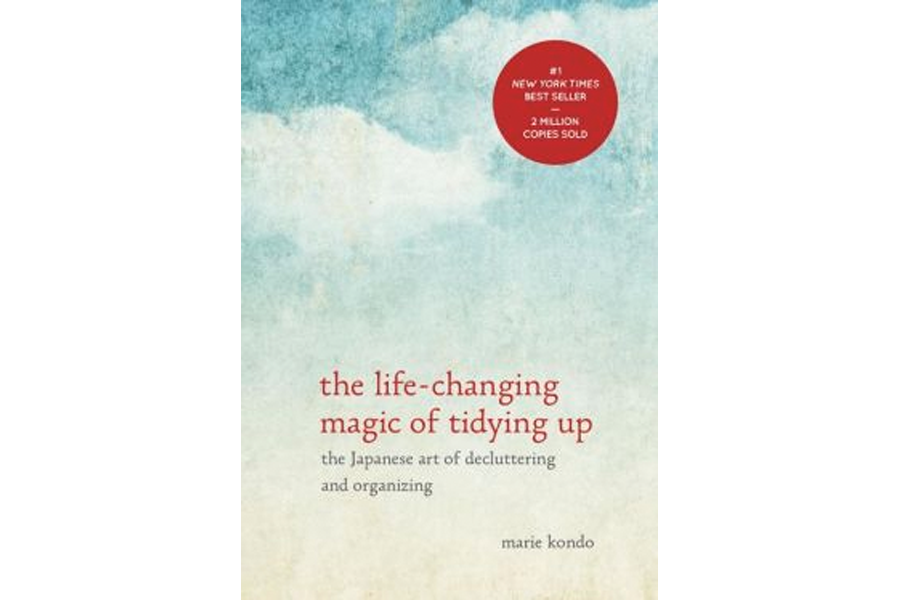

Marie Kondo, the Japanese decluttering expert whose “The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up” is now an international bestseller, tells readers that she now keeps no more than about 30 books in her house at one time.

Thirty? That seems an impossible scale-down for my own library, which numbers a few hundred volumes. But I did wonder, using Kondo’s suggestion, what 30 books I’d choose to keep.

At least 15 of the keepers would be books of special interest to me, though not likely to end up on anyone else’s Greatest Hits list. I’m talking about stuff like high school yearbooks, an old family Bible, the Ford manual my late father once used to fix his car.

That leaves 15 books kept strictly for literary appeal. What would you keep if given such a choice? Here’s my list, which surely would differ from yours. It’s in no particular order of preference.

1. Thoreau’s “Walden.” The classic book about having less and living more. It’s been a touchstone for me since college, reread a dozen times over the years. And I’d console myself with the knowledge that Thoreau’s own personal library couldn’t have been any bigger than the size that Kondo recommends.

2. “Robinson Crusoe” by Daniel Defoe. I’ve tried to read it every summer since boyhood and the book, like any great classic, has grown with me, revealing new themes. A 30-volume library is something our dear castaway Crusoe would have killed for.

3. “A Mencken Chrestomathy.” Henry Louis Mencken’s writing, first encountered in high school, gave me my first sense that journalism could be fun. “Chrestomathy,” by the way, is a fancy word for anthology, and it’s what Mencken chose as the title for this collection of some of his best work. It was just like him to be such a smarty-pants.

4. "The Common Reader.” Virginia Woolf wrote about literature as if it truly mattered more than anything and “The Common Reader” collects her best essays about writers she loved. This book is a continuing education in how to write a sentence.

5. “Collected Poems” by Elizabeth Bishop. Bishop’s sublime verse explores the strange implications of being a human. “One Art,” her poem about the age-old theme of loss and redemption, is enough to keep this book on my must-have list.

6. “Essays” by Michel de Montaigne. Montaigne is timeless company in any season. Lewis Thomas, one of the 20th century’s best essayists, said it was a hopeful sign for humanity that since its first publication in the 16th century, Montaigne’s work has never gone out of print.

7. “Essays of E.B. White.” White’s the one writer I can always read even when I’m not feeling well. His sentences are so graceful that the eye never stops when traveling across the page; the music of his prose goes right to the heart.

8. “One Writer’s Beginnings” by Eudora Welty. Welty could see right through a subject, as this intensely observed memoir of her childhood demonstrates. It grows on me with each reading.

9. “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee. We all know that Lee’s novel of a black man wrongly accused of a terrible crime resonates deeply with social relevance. But what critics overlook is how much fun the book can be when it’s not exploring the dark implications of injustice. Lee perfectly captures how children see and feel.

10. “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain. Twain wrote as Americans talk, conveying his message so authentically that we assume the main characters in “Huckleberry Finn” are as real as we are. They are, in fact, even realer than many of the people I know.

11. “Mornings on Horseback” by David McCullough. McCullough’s books are an abiding reminder that history can be as compelling as a novel. I’d choose “Mornings,” his account of Theodore Roosevelt’s early youth, as the best of his oeuvre.

12. “Collected Works” by William Shakespeare. Any citizen of the human language would have to keep the Bard close at hand. Enough said.

13. “Assorted Prose” by John Updike. Updike was curious about everything, as this seminal collection makes clear. His work is a monument to the power of the inquisitive mind.

14. “The Norton Anthology of American Literature.” I like all the Norton anthologies, which assemble the best writers in a way that cheerfully reminds me of literature as an act of intellectual community.

15. “The Elements of Style” by William Strunk and E.B. White. I have five or six copies of Strunk and White’s classic manual on writing, spreading them around the house so that I can’t help bumping into their uncommon good sense. It would be hard to get by with just one copy. This decluttering business is tough.

Danny Heitman, a columnist for The Advocate newspaper in Louisiana, is the author of “A Summer of Birds: John James Audubon at Oakley House.”