Women’s crime fiction: There was nothing sentimental about it

Loading...

In real life, murder and mayhem are mainly masculine pursuits. In crime fiction, however, women authors have long been major players. For nearly a century, they’ve evolved with the genre from conjuring clever whodunnits to writing tales of action and psychological suspense.

But we’ve mostly forgotten a mid-century generation of female mystery writers who used crime fiction to explore the lives of women in their time and place. Outside of Patricia (“The Talented Mr. Ripley”) Highsmith, their names are obscure even though several of their works became film noir masterpieces like “Laura” and “In a Lonely Place.”

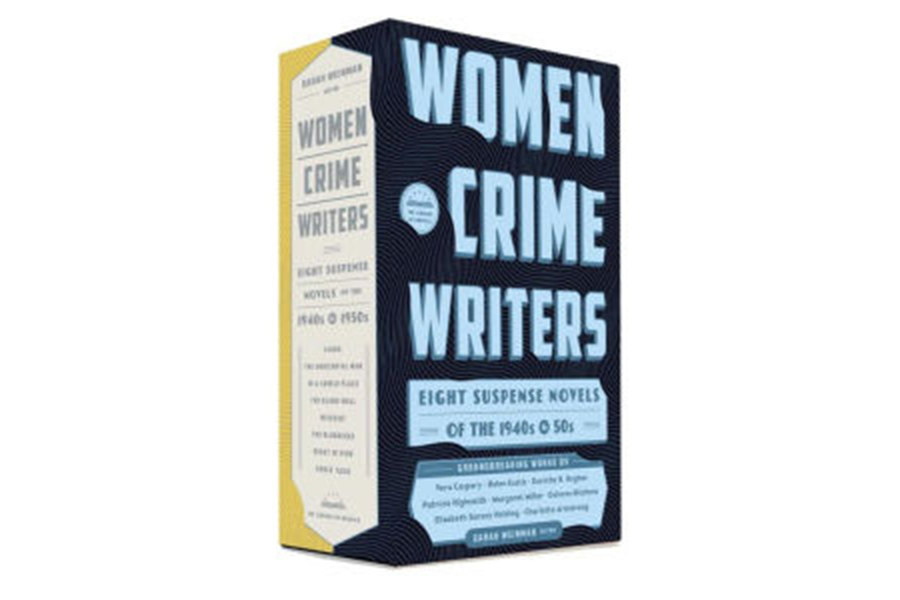

Women Crime Writers: Eight Suspense Novels of the 1940s & 50s, a smashing new Library of America anthology, brings eight groundbreaking mysteries back to life. “Laura” and “In a Lonely Place” are here, allowing readers to examine how a leery Hollywood trimmed their most troubling themes. Six more novels, including one by Highsmith, offer even more suspense and more insight into the changing role of women.

Sarah Weinman, the editor of the anthology, gained notice in 2013 with her book “Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives: Stories from the Trailblazers of Domestic Suspense.” In an interview, she talks about lack of sentimentality lurking in these novels, the feminist leanings (or not) of the authors, and the surprising modernity of these gritty tales.

Q: What draws you to women’s crime fiction of the 1940s and 1950s?

Crime fiction has been a focus and fascination for me for a few years now, and I just got to wonder who were the women before the renaissance, before Marcia Muller, Sue Grafton, and Sara Paretsky helped change female crime fiction.

These women authors in the past weren’t writing cozies or private-eye novels, and they weren’t drawing from Agatha Christie. I found there was this third way. Their stories were more psychologically oriented, featuring women who were married, in toxic relationships, or were alone in some state of loneliness. That’s how I conjured up this idea of "domestic suspense."

Q: What sets these writers apart from their male counterparts?

Women crime writers display a whole bunch of different types of storytelling. There’s this incredible array of characterizations and psychological subtexts examining how people behave and react under stress.

The lack of sentimentality in these books is fascinating. And they really focused on what was frightening and what was fearful. Even if you didn’t see the stabbing on the page, you understood what happened right before or after.

Q: Along those lines, did women authors handle sex and violence differently than the male crime writers of their day?

They had a directness that did not require the violence to be graphic or romantically described. I keep making comparisons to Mickey Spillane’s 1947 “I, the Jury,” which really romanticized and glorified violence. Largely, audiences lapped it up.

Q: Did these authors look at women and their role in the world from a feminist point of view? Do you have a sense that they felt women had too many limitations?

Generally, they looked at the role of women with a gimlet eye and some degree of skepticism. Some defined themselves as feminists, but others did not. Dorothy B. Hughes actively disdained second-wave feminism, even though I would still consider her work, and particularly “In a Lonely Place,” to be a proto-feminist novel.

Q: What are some of the interesting ways that they viewed their male characters?

As psychopaths, clueless or absent figures, would-be saviors who weren't and as teeming with anger. In other words, as people, as humans.

Q: What strikes you as especially contemporary and modern about these books?

It comes down to syntax and tone. They feel tremendously fresh in terms of style, phrasing, characterization.

The books are clearly of their time but, there is this real resonance with contemporary climes. Aren't we still fearful of a killer lurking close by? Aren't we still grappling with complicated, often-toxic family situations?

Q: You’ve mentioned “In a Lonely Place” as probably being your favorite of the novels. Without giving too much away, why you like it?

Because Hughes manages the brilliant trick of telling a story from an unreliable narrator who thinks he knows what is going on through his narcissistic, psychopathic inner self. At the same time, she’s cluing in the reader to what is really going on outside of his viewpoint.

Every time I reread it, I try to pick apart how Hughes made it work. And of course, it's a wonderful novel of post-war L.A., describing a kind of collective post-traumatic stress disorder even though the term was decades away from being coined.

Q: How did Hollywood de-fang and masculinize the Humphrey Bogart movie version of “In a Lonely Place”?

The story as Dorothy B. Hughes wrote it simply could not have been filmed in a McCarthy-era, Hays Code-driven Hollywood. And director Nicholas Ray wanted to tell a different story. It's not what Hughes wanted, but the film is a stunning work of art that’s separate from the book. It should be viewed as something of a parallel universe.

Q: What should readers take from these books?

I hope the books not only hold up but entertain and give them them hours of unfettered pleasure reading.

But I don’t want just people to read the eight novels. I want them to seek out other other writers who were publishing beside them. There’s a whole generation of women who wrote crime novels and haven’t gotten their due. I want them to be restored to their rightful place in the annals of the crime fiction world, to have their place.

Q: But not "A Lonely Place"?

You said it, not me.

-- RANDY DOTINGA