The Fed blurred the line between monetary and fiscal policy. Who'll clarify it?

Loading...

Economists have traditionally drawn a sharp distinction between monetary and fiscal policy.

Monetary policy should try to promote growth and limit inflation by setting short-term interest rates, managing the money supply, and providing liquidity during times of financial stress. Fiscal policy should also encourage growth and, more broadly, promote the general welfare through careful choices about spending, taxes, and borrowing.

The Federal Reserve has responsibility for monetary policy, while Congress and the President handle fiscal policy.

That clean distinction was one of many casualties of the financial crisis. As credit markets froze, the Fed pursued unconventional policies that blurred the line between fiscal and monetary policy.

For example, it purchased more than $1 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issued by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, created new lending facilities for commercial paper and asset-backed securities, and provided special support for such key financial institutions as AIG, Bank of America, and Citigroup.

Those actions differed from conventional monetary policy in two ways.

First, they exposed the Fed to more financial risk. Short-term Treasury securities, the Fed’s usual fare, carry no credit risk and almost no interest rate risk. In contrast, the Fed’s new portfolio has healthy doses of both.

Second, in several cases the Fed offered to purchase financial assets at above-market prices or, equivalently, to make loans at below-market interest rates. In effect, the Fed chose to subsidize some specific financial activities.

Both changes increased the Fed’s fiscal importance.

Most visibly, Fed profits have jumped as its portfolio expanded and it acquired higher-yielding assets. Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that Fed profits will hit $77 billion in 2010, up from $32 billion in 2008. That makes them the fourth largest source of federal revenues, after personal income, social insurance, and corporate income taxes, but ahead of estate and excise taxes. Actual returns could be higher or lower, however, depending on how well its investments perform.

Also important, though less visible, are subsidies implicit in some of the Fed’s financing programs. The Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF), for example, offered favorable long-term funding to investors who wanted to finance investments in securities backed by auto loans, student loans, and certain other types of debt. Similar programs provided favorable funding to support commercial paper markets and to assist AIG, Bank of America, and Citigroup. CBO recently pegged the initial cost of the resulting subsidies at $21 billion.

Not all programs created subsidies, however. CBO concluded, for example, that the MBS purchase program did not involve subsidies because the Fed made its purchases at market prices.

To be sure, the Fed’s fiscal initiatives were dwarfed by the explicitly fiscal actions taken by Congress and Presidents Bush and Obama. The Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP), for example, was originally estimated to involve subsidies of $189 billion (a figure that has fallen as financial markets have healed), and support to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac has added tens of billions more. Still, CBO’s estimates do highlight the Fed’s move into fiscal territory as it battled the financial crisis.

Those steps were appropriate given the severity and suddenness of the crisis, but have fueled concerns about the Fed’s scope of authority. Some members of Congress, for example, have questioned whether the Fed should be able to engage in even moderate amounts of fiscal policy without congressional oversight. Their increased interest in Fed oversight, in turn, has raised concerns about defending the Fed’s traditional independence in making monetary policy.

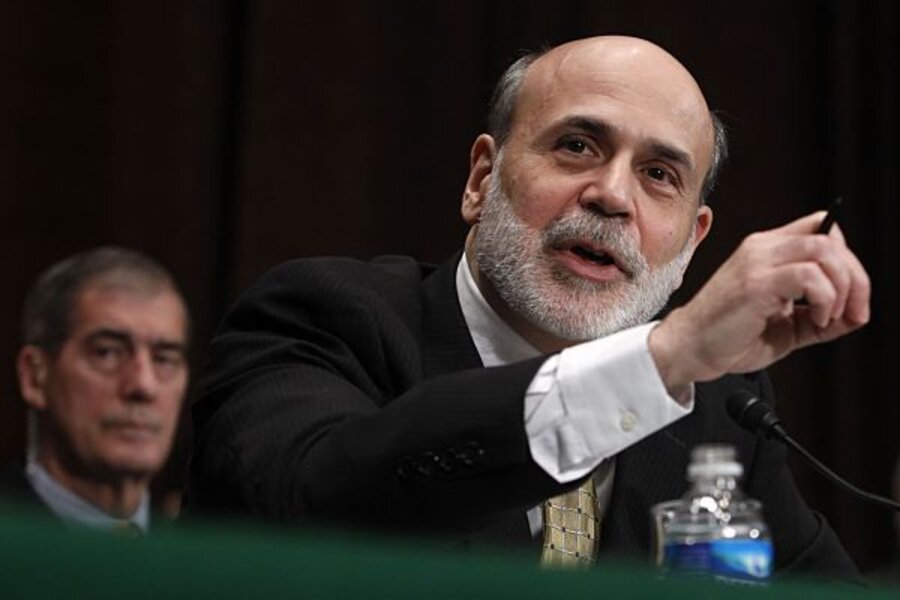

As Chairman Ben Bernanke argued in a speech last week, maintaining the Fed’s independence in monetary policy would be easier if policymakers would “further clarify the dividing line between monetary and fiscal responsibilities.” Let’s hope such guidance comes along before the next financial crisis strikes.

Add/view comments on this post.

------------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of the best economy-related bloggers out there. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by the Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own, as is responsibility for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here. To add or view a comment on a guest blog, please go to the blogger's own site by clicking on the link above.