Did a chemical engineer reduce big city crime?

Loading...

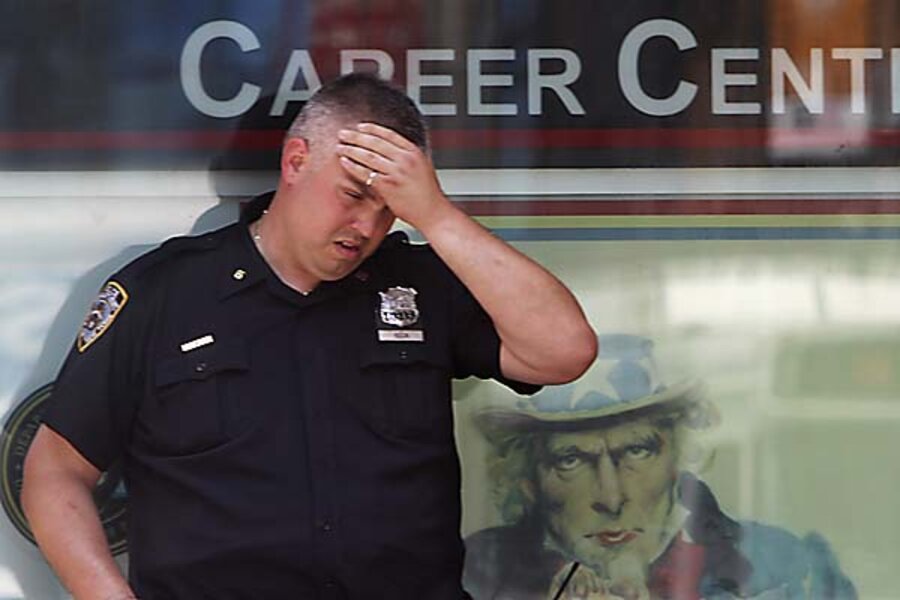

We know that big city crime has fallen sharply over the last 20 years. The experts continue to debate why this progress in quality of life has taken place. John Sinfelt may have caused this progress. As his obituary sketches, he was a pioneer in developing unleaded gasoline. The funny thing is that he did his research for Exxon. So big city mayors owe Exxon a big thanks for sponsoring his research. Below, I talk about causality but here are the facts.

How could the introduction of unleaded gasoline cause the crime decline that starts in 1990?

I have blogged about this before but we must return to the work by Amherst's Jessica Reyes.

Building on the original Donohue and Levitt research agenda, she creates a state/year level data set to study crime dynamics and introduces a funky new explanatory variable --- as I recall her new variable is a measure of lead emissions in that same state 18 years before. Her story is as follows; if you are born in 1972 in a state where there is plenty of lead emissions then you are exposed to high ambient lead concentrations and this has bad health effects and developmental consequences. These kids are more likely to grow up and become criminals (not all but some). Flash forward to the year 1990 and the birth cohort from 1972 are now age 18 and commit crimes (see the NYC murder graph above).

Starting in 1975, the U.S phased out leaded gasoline so new birth cohorts were exposed to less lead and the crime rate starts falling 18 years later when the new teenagers are less messed up.

I agree that this is a "wild" hypothesis but note that her hypothesis can also explain the increase in crime over time seen above over the years 1960 to 1990. After WW II, the U.S became more affluent and vehicle ownership soared and people drove more miles using leaded gasoline and this increased the ambient lead concentration (since the EPA didn't exist nobody was monitoring these emissions).

John Sinfelt's work helped to reverse this trend and is a powerful example of how human capital and innovation can protect us from environmental externalities. People ask me why I'm optimistic about our future quality of life. I point to guys like him.

Add/view comments on this post.

--------------------------

The Christian Science Monitor has assembled a diverse group of the best economy-related bloggers out there. Our guest bloggers are not employed or directed by the Monitor and the views expressed are the bloggers' own, as is responsibility for the content of their blogs. To contact us about a blogger, click here. To add or view a comment on a guest blog, please go to the blogger's own site by clicking on the link above.