Gregg Williams audio and Saints bounty program test my football faith

Loading...

| Los Angeles

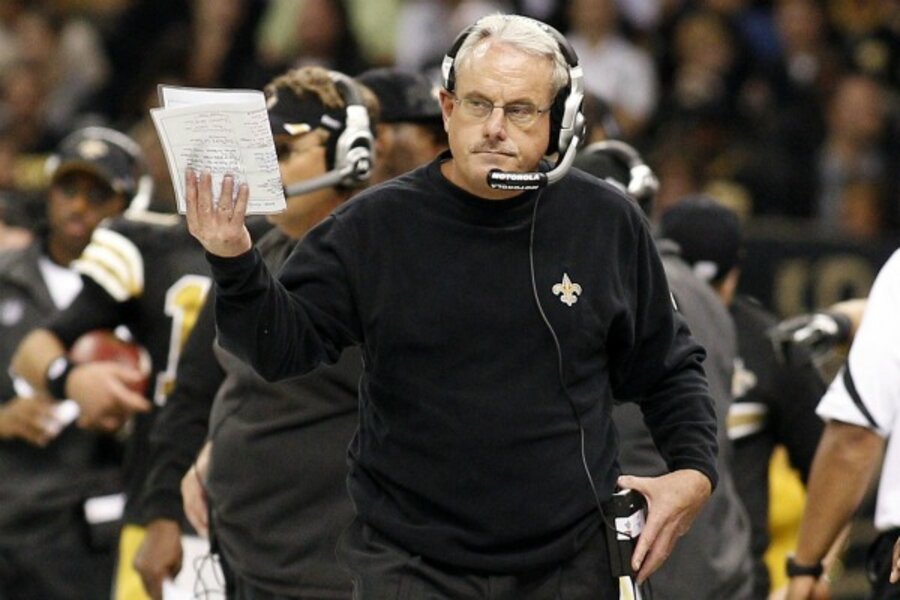

It’s hardly a secret that professional football is a violent game, with potentially grave consequences for players long after retirement. But now comes the release of an audio recording in which New Orleans Saints former defensive coordinator Gregg Williams orders his players to injure their opponents. The recording has prompted outrage even from battle-hardened ex-players, and from the legions of loyal fans like me, who spend fall Sundays cheering the bone-crunching collisions on the field.

I grew up in the Wisconsin football culture of the legendary Vince Lombardi, who famously told his players to think of three things only: “God, your family, and the Green Bay Packers.” Indeed, football for me has always been a kind of faith, rooted in long-past Sunday afternoons with my father, when my mom served us slabs of Wisconsin cheddar well before we called ourselves Cheeseheads.

To this day, decades after those Packer glory years, I follow the Green and Gold with a fierce devotion – taping little Packer helmet lights to my television, laying out Packer Russian dolls like a string of talismans, even putting off international reporting trips in deference to the playoff schedule.

But now the sickening diatribe of Mr. Williams, on the eve of a January playoff game against the San Francisco 49ers, is testing that faith. Williams ordered his players to inflict a potentially career-ending hit on one receiver’s knee, and to target the heads of players who had previously suffered concussions. “Kill the head,” said Williams, “and the body will die.”

The coach’s rant brings to light a fundamental question, upon which rests the NFL’s relationship with its fans: Was Williams’s behavior, and the Saints’ secret two-year “bounty program” that offered cash to “take out” opposing players, an anomaly? Or does the program, and the coach imploring his players to maim their opponents, open a rare window to the essential truth of our national pastime?

The NFL, and the multibillion-dollar entertainment industry of networks and pundits built up around it, would like us to believe that Williams was a rogue actor, aided by fellow coaches who looked the other way. The league acted swiftly, doling out multiple suspensions, including to Saints head coach Sean Payton for the entire 2012 season, and an indefinite suspension for Williams that could well turn into a lifetime ban. (Last Monday, NFL commissioner Roger Goodell rejected the appeals of Payton and others.)

But some ex-players seem to think Williams was acting in accordance with a larger NFL culture. As former NFL quarterback Tim Hasselbeck has tweeted: “i don’t think i was ever on a team where a coach didn’t mention an opposing players injury.” And this: “....never on a team that didn’t talk about opponent injuries.head,ribs,hamstring.” Ross Tucker, a former offensive lineman who is now a commentator for Fox, added: “People that never played/coached wouldn’t know that isn’t unusual.”

So it “isn’t unusual” for coaches to urge a head hit on a player with a history of concussions? If so, given what the medical community tells us about the link between head trauma and dementia, how is this not criminal behavior? And how do we as fans reconcile our love for the game with coaches who seek to afflict opponents with lifelong damage?

In “Cruelty and Civilization,” the French author Roland Auguet depicts the violent Roman games as “a force vital for the functioning of an Empire,” and “a kind of public opiate for the citizens of Ancient Rome.”

Is professional football the 21st Century American equivalent? Witness the endless loop of mythologized Lombardi speeches; the super-slow motion of a football spiraling downfield, accompanied by a surging soundtrack; the soft-focused pre-game features on players who’ve overcome hard times. They amount to a big distraction from the truth of it all: that the world of the NFL is so much more violent and warlike than even the most diehard fans imagined; so much more like the fight-to-the-death gladiator days than any of us fans really care to think about.

“You can put it on your flat-screen TV, put glitz and glamour on it with the girl singing the anthem before the game, have the boys and girls club out there at halftime but it’s still a war out there, man,” the former NFL defensive lineman Chidi Ahanotu told Tyler Dunne of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “That’s how it is. It’s carnage.”

That carnage has been revealed, at least for one moment, with one coach’s demented rant, and the morally twisted pay-to-injure program he oversaw. For the NFL, the challenge is to limit the damage, even as it defends itself against multiple lawsuits from ex-players who contend the league hid the crippling dangers of concussions.

But now we fans have had a glimpse of how the bloody sausage is made. Carnage, Bountygate, traumatic brain injuries: Over the years, we’ve watched our favorite sport grow increasingly barbaric. How long will we fans pretend not to notice?

It’s good that the NFL, after years of denial, has finally endorsed measures to reduce head trauma on the field. I applaud its tough justice with the Saints bounty program. But I want more than assurances that the program was an aberration. Commissioner Goodell needs to keep the heat on. No NFL locker room should be safe from scrutiny.

As a lifelong NFL fan, I need to know that I’m not financing cruel blood sport.

Sandy Tolan is associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at USC. He is author of “The Lemon Tree: An Arab, a Jew, and the Heart of the Middle East.”