The case against mail-in voting

Loading...

| Cleveland

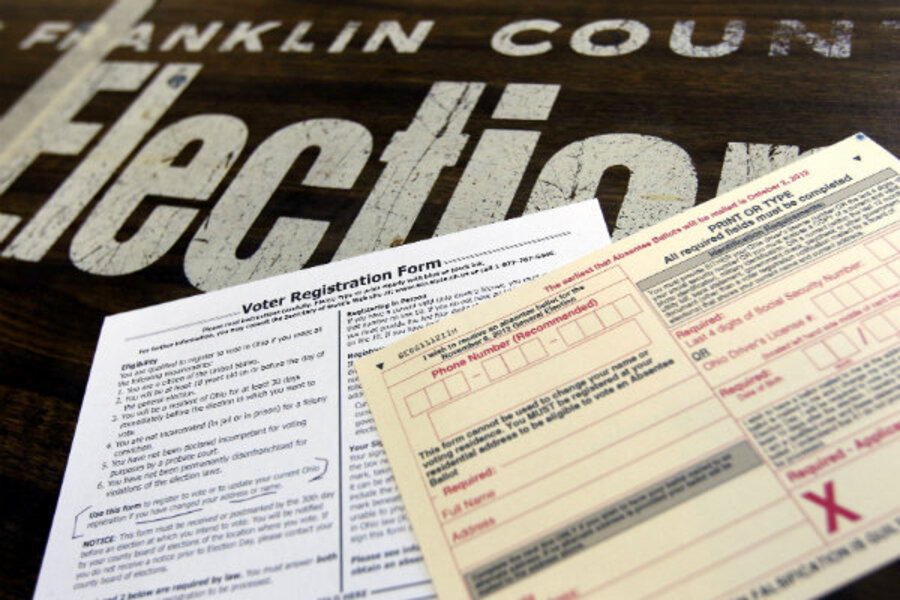

Roughly 30 percent of the ballots cast in the 2008 presidential election were cast early and mostly by mail. CNN estimates that the number of early voters may reach 40 percent in this upcoming election. Right now, voting is going on in more than half the states.

Many secretaries of state love early voting: fewer chances for voting machine malfunctions, hanging chads, voter ID skirmishes. And it’s easier on the system – the electoral equivalent of utility companies getting customers to spread out their electric use to avoid big spikes.

The post office has to love early voting by mail. That’s a lot of business, and, boy, do they need it.

Many lovers of democracy also love early voting because it increases access for the elderly, the infirm, and working people who can’t afford time away from the job.

But some fans of democracy and civic engagement aren’t too fond of the idea. Norman Ornstein of the American Enterprise Institute put it this way in a 2004 piece in the Economist:

“In America, individuals join their neighbors at a local polling place, underscoring their role as a part of a collective society, then go into a curtained booth to make their choices as free individuals. Every conceivable step should be taken to make the votes cast on Election Day easy to do – longer hours, ample poll workers and voting machines, easier registration, and so on. But we should not make voting the equivalent of sending in a Publishers Clearing House contest form.”

I share Mr. Ornstein's views. I vote "no" on mail-in voting.

I don’t just want my vote to count; I want the act of voting to count. I want to stand in line, the longer the better, and mingle with my neighbors. I want to make small talk with the earnest and dedicated senior citizens working the polls. I want the act of punching my ballot to connect me to my grandparents who came to this country at the turn of the last century in part so they could have a voice in their government. I want to stand symbolically in line with my black brothers and sisters who fought and died for voting rights as recently as the 1960s.

I understand that it’s no less a vote if you do it from your kitchen table while you pay your monthly bills. It seems to me it’s just less a joy and more a chore.

We have so few opportunities these days to stand shoulder to shoulder with other citizens. We live so much of our lives online, where it’s easy to practice the first amendment with the click of a button but difficult to participate in real discourse.

When I heard Mitt Romney write off 47 percent of the country as freeloaders (he stood by those comments for almost two weeks before fully denouncing them) and Ron Paul and other Republicans insist that those who can’t afford insurance should fend for themselves, I can’t help wishing they had to spend more time rubbing elbows with the 47 percent. That might temper some of their positions.

The wealthy in this country live increasingly segregated lives. They do their business online or through proxies. They don’t wait at the bus stop or stand in line at the post office. They don’t wait in emergency rooms with their fellow citizens just to see a doctor. They have so few chances to mingle with citizens of lesser means. So to the extent that going to the polls affords that opportunity – and it does in urban areas where neighborhoods are more economically diverse – then it’s a good thing.

Civil society depends on opportunities for citizens to practice civility.

So if you haven’t mailed in your ballot yet, consider this election day an invitation to a wonderful Open House in the heart of your neighborhood: a free, all-day event, a celebration of freedom and democracy and community. Look for the posters and banners, and when you leave, don’t forget to take your parting gift: that lovely lapel sticker that says, “I Voted Today.”

Jim Sollisch is creative director at Marcus Thomas Advertising.