How to choose a justice

Loading...

Much is being said about how quickly the Senate should act on President Obama’s nominee to the US Supreme Court, Judge Merrick Garland. Just as the president has discretion in choosing a nominee for a vacant seat, so the Senate also has discretion in determining the speed with which it performs its role to vote on the nominee.

The Constitution sets no timetable. But it seems clear that the Garland nomination now fully embodies a politicization of the nomination process, something that can be seen in Senate votes regarding the current justices.

In 1986 Justice Antonin Scalia, whose death created the vacant seat, was confirmed by a 98-to-0 vote of the Senate. And it must be generally agreed that he was not a “compromise” or middle-of-the-road candidate but a justice with a strong conservative bent. Yet senators from both parties unanimously allowed then-President Ronald Reagan to appoint a justice whose views were compatible with his own.

In 1993, President Bill Clinton nominated Ruth Bader Ginsburg, generally considered to be a liberal jurist. The Senate agreed that she was qualified for the post and by a vote of 96 to 3 allowed Mr. Clinton to appoint a justice with views compatible with his own.

But more recent nominees have fared less well. President George W. Bush’s nominee, Samuel A. Alito Jr., was confirmed 52 to 48. Mr. Obama’s first nominee, Sonia Sotomayor, was approved by just 69 to 31, and his second previous nominee, Elana Kagan, by 63 to 37.

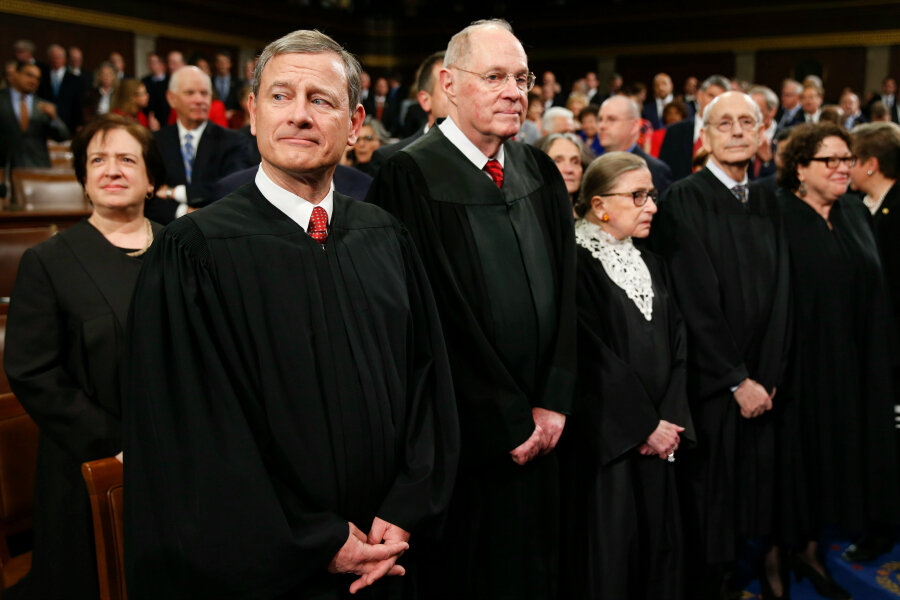

In a speech given at a Boston law school only days before Justice Scalia’s death, Chief Justice John Roberts bemoaned the politicization of the nomination process. Referring to recent Senate votes on Supreme Court nominees, Chief Justice Roberts said “the votes were, I think, strictly on party lines for the last three of them, or close to it, and that doesn’t make any sense. That suggests to me that the process is being used for something other than ensuring the qualifications of the nominees.”

He also reminded his audience that the court does not consider itself to be a collection of party loyalists.

“We don’t work as Democrats or Republicans,” said Roberts, who was appointed by Republican President George W. Bush, “and I think it’s a very unfortunate impression the public might get from the confirmation process.”

Does placing emphasis on legal competence rather political viewpoints mean that the Senate is no more than a rubber stamp for a president? Hardly. As Jonathan Chait points out in New York magazine, “the Senate has withheld its consent from nominees deemed too extreme” in their views. But what is happening now, he says, seems to be a full-on “blanket opposition to any nominee from the opposing party.”

In theory, if the majority party in the Senate is from one party, and the president from the other, the Senate could continue to stall until the next election to see if a nominee might be more to its liking. In this scenario the Supreme Court could go years without a full roster of justices, perhaps tied up in a series of 4-to-4 decisions. In this highly politicized environment appointments to the court would be possible only when the presidency and the Senate majority were held by the same party.

Traditionally the office of president has been given some deference in selecting a person for the nation’s highest court. That era seems to be over as ideological conformity and power politics take over.

Members of the Senate, and American citizens, need to think deeply about whether this change improves or diminishes the nomination process and the future of the Supreme Court.