Maine looks north, hoping to become a gateway to the Arctic

Loading...

| Portland, Maine

For government and indigenous officials from around the world, the Arctic Council meeting here in October was a week-long opportunity to discuss shared Arctic issues like sustainable development and protecting ecosystems.

For the people of Maine, it was a week-long opportunity to reconnect with their rich Arctic history, and to imagine a future where Maine is not a remote and limited corner of a powerful country, but a gateway to, and steward of, the rapidly changing and increasingly active Arctic region.

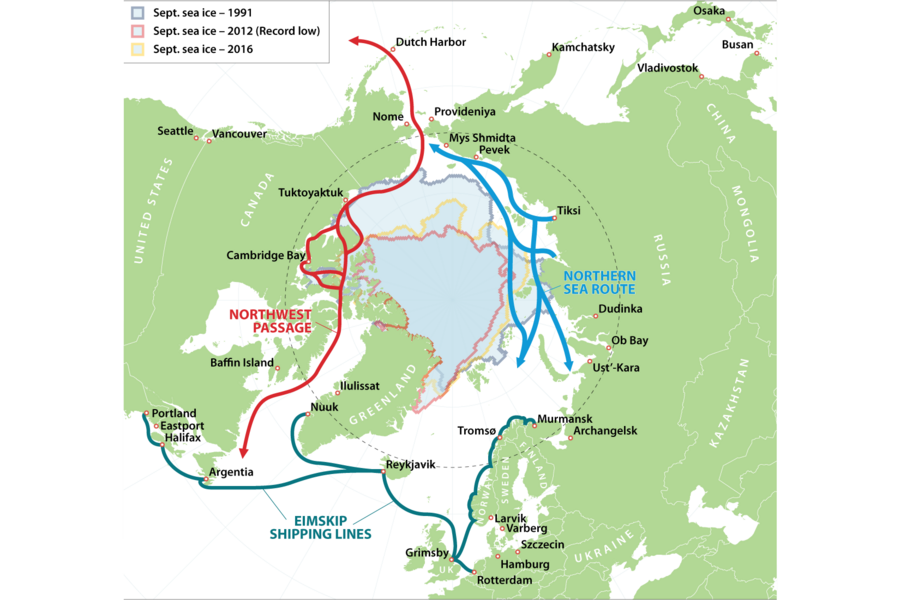

The increased activity is, of course, in large part a result of climate change. The Arctic is warming at a rate almost twice the global average, and the 13 smallest recorded winter maximums for Arctic sea ice have come in the past 13 years, according to NASA. Meanwhile, Arctic sea routes are becoming more navigable and natural resources are becoming more accessible.

Maine’s economy has stagnated in recent years, and businesses in the state are eyeing the Arctic for new opportunities. They are not alone. Scientists and politicians, even artists and chefs, in the state are shifting their focus north as well. In all, Mainers see the chance for their little state to exercise leadership, to bring its traditions of environmental stewardship to bear in a region where it’s most needed, and to seek much-needed economic benefits.

“The North Atlantic is just full of really interesting market opportunities,” says Patrick Arnold, president of SoliDG Inc., the company that operates Portland’s International Marine Terminal. “You can go through the history of Maine and watch as certain industries depart,” he adds. “This connection with the High North is really a new lease on life for Maine.”

The opportunities – including new shipping prospects through an Arctic with diminishing sea ice – shouldn’t be reduced to a simplistic story line that climate change will be good for Maine. Scientists who study Earth’s warming temperatures, and who widely attribute the shift to human activities, predict a host of adverse consequences here as elsewhere.

For the Arctic region itself, concerns were underlined Dec. 20 as President Obama and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau outlined joint plans for safeguarding the region’s marine life alongside economic development. The plans included shielding vast stretches from offshore oil drilling and steps to support indigenous peoples whose livelihoods and cultures are at risk.

“Changes in the Arctic are occurring on so many different levels,” says Susan Kaplan, director of the Arctic Studies Center at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. “What I hope for Maine is, as it looks to its involvement in the North, that it acts culturally and environmentally responsibly.”

'A global player'

Maine’s northern tilt is growing from within, but a crucial impetus came from outside. Back in 2013, an Icelandic steamship company called Eimskip was looking for a port to be its new US base.

Larus Isfeld, the company’s US managing director, was scouting around and visited Portland. The city’s maritime trade had been declining for about half a century, but Mr. Isfeld called his boss and said that, for the first time since moving to the US 20 years earlier, he felt like he was back home in Reykjavik.

After finding the local government and community “very supportive,” Eimskip decided to set up shop. Its activity at the port has grown 20 percent every year since, and now three vessels come into the city every month, connecting the state with cities like Rotterdam, Reykjavik and Tromsø, Norway.

“Having Eimskip here connecting us to these fairly close locations, I think we’re feeling more like a hub now,” says Dana Eidsness, director of the Maine North Atlantic Development Office (MENADO). “From this point forward I think there’s a recognition that Maine is a global player.”

With the commercial activity came a symbolic call to action as well.

Icelandic President Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson came to Portland in 2013, just after Eimskip had relocated, and said in a speech that "Iceland and Maine are strategically placed in this new global transportation system.”

"There is a new ocean opening on planet Earth," he added. "It's a reality, whether we like it or not."

The trade relationships aren’t huge for now. The goods Eimskip hauls range from frozen fish and dry goods to building materials and small silvery silicate rocks from the Faroe Islands used in steel smelting. The rocks cost a couple cents each.

But this trade can be vital for isolated and import-dependent nations like Greenland and the Faroe Islands, and it can also provide Maine something it has not enjoyed for decades: reliable markets for their niche and high-quality local products.

“Maine only has 1.3 million people. It doesn’t take a lot of new opportunities to really open some new doors for Maine businesses,” says Mr. Arnold at Portland’s marine terminal.

A rebirth for Eastport?

Just ask Captain Bob Peacock, who imports salmon from northern Norway once or twice a month via Eimskip.

As a resident of Eastport, a town at the northeastern-most point of Maine, he has much bigger hopes for Maine’s burgeoning northern connections. [Editor's note: This paragraph has been corrected by to remove an inaccurate time-zone reference for Eastport, which is on Eastern Standard Time.]

Those hopes are largely pinned on the increasingly accessible sea routes through the Arctic Ocean, particularly the Northwest Passage running from Alaska to the Atlantic. The extent of summer sea ice is still highly variable year by year, but the decades-long trend has been steadily down.

The southern route of the Passage has been navigable every summer since 2007, while the northern route has been navigable for six summers between 2007 and 2016. As the Passage thaws, Mr. Peacock hopes, Maine “can become the closest point on the [US] East Coast to China.”

The economic potential is significant, particularly for a city like Eastport, located in one of the poorest US counties east of the Mississippi. Once a hub of New England’s fishing industry, its population is now just 1,300 – a quarter of its 1900 peak.

The city has several natural advantages, including having the easternmost and deepest natural harbor in the lower 48 states. For the hulking, deep-bottomed and ice-resistant ships that may soon be coming through the Northwest Passage, Eastport’s fjord-like harbor may be the only Eastern US port deep enough to fit them.

“We could be the loading dock for the East Coast of the United States,” says Chris Gardner, director of the Eastport Port Authority.

The port has been slowly reawakening. It reopened in the 1970s and had its busiest year in 2012, and it’s spending $10 million to install a new conveyor belt system. But there are still 200 or more days a year with no ships in the port, and the city has been lobbying to build rail access to the port.

Eastport “is struggling to find its way. It has the God-given aspect of the deepest sea port, but it’s not connected to the rest of the world,” says Mr. Gardner. “We have all these natural advantages, and we have to do a better job capitalizing on it.”

Not plain sailing yet

There have been hints and tastes of Arctic shipping in Eastport. In 2012, a cruise ship called The World navigated the Northwest Passage before docking at Eastport.

But there are also plenty of challenges. Traversing the Northwest Passage is risky, costly, and may not become routine for decades. And other issues raise questions about Arctic development, from disruptions of indigenous communities to the difficulty of search-and-rescue operations and oil spill response.

Maine’s most realistic hopes may be modest ones.

"[Maine] is not going to be a huge Arctic player, but within the North Atlantic it's certainly having a growing role," says Mia Bennett, a PhD candidate at UCLA researching Arctic development and transportation infrastructure.

Whatever their role may be, Mainers are preparing.

Ms. Eidsness, director of MENADO, is a US delegate to the Arctic Council and sits on the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment working group. Ralph Pundt, a professor at the Maine Maritime Academy who has voyaged to Greenland and Antarctica, is teaching an advanced course at the school on polar transit.

“We have possible opportunities up there, but we have huge responsibilities to protect that area, and it’s my concern that we won’t,” says Professor Pundt.

Arctic shipping is bound to increase at least somewhat, whether Maine is involved or not, he adds. The question will be, “Can we support growth in that area without destroying it?”

From science to clean energy

Shipping is just one manifestation of Maine’s northern focus. It’s also emerging in arenas like scientific research, manufacturing, and the arts.

Maine scientists are among those at the forefront of monitoring and researching how the Arctic is changing.

In part that’s because Maine is also starting to see and feel the effects of climate change. For the past decade the Gulf of Maine has been warming twice as fast as the rest of the world’s oceans, contributing to a collapse of the region’s storied cod fishery. There have been some positives – lobster distribution has shifted northward, helping Mainers pull in record sales for six straight years – but the state’s coastline, much like Arctic waters, is experiencing rapid change that could disrupt economies and subsistence living.

“Maine, Norway, Alaska are all places that are changing really quickly,” says Andy Pershing, chief scientific officer at the Gulf of Maine Research Institute in Portland. “Are there common lessons we can learn about how to manage fisheries in a changing climate?”

Meanwhile, Maine businesses are also finding ways to help develop the Arctic in a clean and sustainable fashion.

Harbor Technologies, an Augusta-based company that manufactures infrastructure made from composites – durable, lightweight materials like fiberglass and carbon fiber – has been making pilings for piers in Eastport and Alaska. In 2013, the company sent parts for a bridge being built in Norway. And now, after being bought by a larger composites company last year, they are looking for potential clients in the Canadian Maritimes and far North, according to Erik Grimnes, director of business development for the company.

A Portland-based business, the Ocean Renewable Power Company (ORPC), is building small-scale tidal and river power generators that can convert energy from tides and rivers into electricity for small Arctic communities long dependent on diesel fuel.

Last year the company installed a river power system in the remote village of Iguigig, Alaska, training locals to install and operate it, and reducing the village’s need to import costly diesel fuel.

This kind of technology can tick multiple boxes at once, especially for Arctic communities, says Chris Sauer, the company’s president and CEO. It can replace carbon-intensive diesel fuel with clean energy, without disrupting the local marine environment, and it can provide people with training that could create jobs and other economic opportunities in the future as the technology expands.

“We’re part of a solution that’s badly needed,” he adds. “And it’s not just an energy solution. It’s an environmental solution and an economic solution.”

The tidal energy systems are being deployed right in Maine as well as in places like Nunavik, in northern Canada.

Cultural stirrings

Looking at all these changes unfolding around and within Maine, Justin Levesque wants to put an artist’s perspective on them. So in September 2015, the Portland-based photographer boarded an Eimskip vessel and spent nine days traveling to Reyjkavik. He took photographs and interviewed the crew, eventually combining it into the ICELANDx207 exhibit, which has been on display around the city since the Arctic Council meeting in October.

“I think it’s important to have artistic witnesses and artistic viewpoints on these emerging ideas,” he says.

These cultural exchanges are not limited to art. While the Arctic Council was in Portland, so was Inunnguaq Hegelund, a star chef from Greenland who spent the week working in the restaurant Vinland making Greenland-inspired dishes.

For his part, Mr. Levesque wants to bring his photographic observations further north, particularly in the context of Arctic climate change. So next year he will travel to Svalbard, a mountainous archipelago between Norway and the North Pole, for a three-week artist residency aboard a tall ship.

“We’re in the middle of it, and it’s hard to know what’s going to happen, but I think that’s why we need to provide access through cultural things,” he says. “If we can be voices in that conversation [about the Arctic] I think it’s great.”

As in other Arctic-oriented places, frictions could emerge as Maine pursues the goals of both northern economic development and environmental stewardship. At the moment, though, the state seems to be managing the navigation of that twin path.

“Maine is not a powerful state, but we are a very environmentally minded state,” says Paul Mayewski, director of the Climate Change Institute at the University of Maine. “There will be much, much more in the future. We have the opportunity to create a positive example.”