Survey: Galaxies become cannibals as teens

Loading...

A new survey of galaxies' growing pains found that these cosmic objects change their eating habits during their adolescent phase, becoming more cannibalistic.

Astronomers used the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope in Chile to examine a band of galaxies during what could be considered their teenage years — about 3 to 5 billion years after the Big Bang that is thought to have created the universe.

In their survey, the researchers found that at the start of this dynamic phase, galaxies prefer to snack on smooth flows of gas, but as they mature, they will consume other, smaller galaxies.

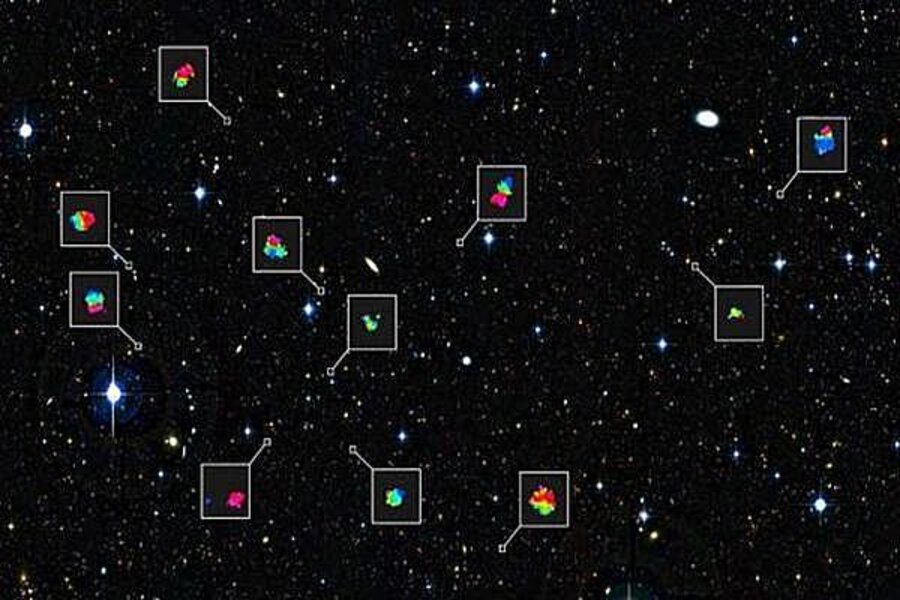

These galaxies examined through the VLT are located in a tiny patch of sky more than 40 million light-years away, in the constellation of Cetus (the Sea Monster).

Astronomers have known that the earliest galaxies in the universe were much smaller than the spiral and elliptical galaxies that now fill the cosmos, but how these galaxies bulked up over time was largely a mystery.

The new survey offered novel details about the eating habits of teenage galaxies to help scientists grasp how galaxies grow. [See photos & video of the teenage galaxies]

"Two different ways of growing galaxies are competing: violent merging events when larger galaxies eat smaller ones, or a smoother and continuous flow of gas onto galaxies," study lead author Thierry Contini, of the Research Institute in Astrophysics and Planetology in Toulouse, France, said in a statement. "Both can lead to lots of new stars being created."

The results of the new study suggest that many galaxies went through a period of growing pains when the universe was 3 billion to 5 billion years old, ESO officials said. Smooth flows of gas seem to have dominated the growth of galaxies in the very young universe, while galaxy mergers came more into play later.

Since the galaxies in the survey are so distant, they appear only as small, faint specks in the sky, but the data collected by the researchers helped them make maps of how different parts of the galaxies are moving and what they are made of, ESO officials said.

"For me, the biggest surprise was the discovery of many galaxies with no rotation of their gas," said study co-author Benoît Epinat. "Such galaxies are not observed in the nearby universe. None of the current theories predict these objects."

The findings also allowed the astronomers to compare the ingredients of these teenage galaxies to the more massive spiral and elliptical galaxies that now populate the universe.

"We also didn't expect that so many of the young galaxies in the survey would have heavier elements concentrated in their outer parts — this is the exact opposite of what we see in galaxies today," Contini said.

The researchers plan to follow up this study with more detailed observations using future instruments on the VLT and other ground-based telescopes.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.