How did an entire star system's worth of dust just vanish? Scientists baffled.

Loading...

| Washington

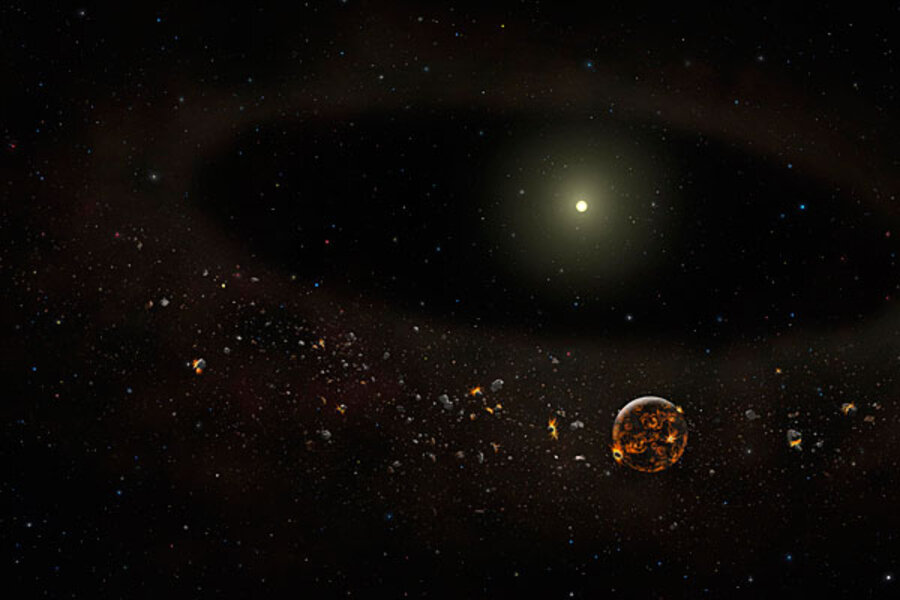

In a cosmic case of "now-you-see-it, now-you-don't," a brilliant disk of dust around a Sun-like star has suddenly vanished, and the scientists who observed the disappearance aren't sure about what happened.

Typically, the kind of dusty haloes that circle stars have the makings of rocky planets like Earth, according to Ben Zuckerman, one of a team of researchers who reported the finding on Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Composed of warm dusty material, these disks can be seen by telescopes looking for infrared light. This one was first seen in 1983 by NASA's Infrared Astronomical Satellite around the young star TYC 8241 2652. It glowed for a quarter-century before disappearing in a matter of 2-1/2 years.

An image taken May 1 by the Gemini observatory at La Serena, Chile, confirmed that the disk was gone.

Astronomers are accustomed to watching events that have unfolded over millions or billions of years, so seeing a bright ring depart from view in less than three years was an eye-blink in the astronomical context, Zuckerman said by telephone from the University of California-Los Angeles.

When it was there, the disk was about as far from its star as Mercury is from our Sun, or about half the distance between the Sun and Earth, Zuckerman said.

The disk's star is a relative baby, just 10 million years old, compared to our middle-aged 4.6 billion-year-old Sun, he said. The disk orbiting close to it harbored "a huge amount of ... tiny dust particles, trillions and gazillions of them."

"So much dust orbiting so close to a young star implies that rocky planets similar to the terrestrial planets of our own solar system were in the process of forming around this star," he said. But all of a sudden, this potential planet-maker was absent.

"We don't really know where the dust came from in detail, and we certainly don't know what caused it to disappear so quickly," Zuckerman said.

Carl Melis of the University of California-San Diego, a co-author of the study and leader of the discovery team, said in a statement there are at least two ways the disk might have vanished. The dust particles might have been dragged into the star or caromed out into space though "none are really compelling," he said.

This discovery has the potential to make astronomers re-think their ideas about what happens as solar systems form.

TYC 8241 2652 is about 450 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Centaurus (The Centaur). A light-year is about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion km), the distance light travels in a year.

(Reporting By Deborah Zabarenko; Editing by Marilyn W. Thompson and Cynthia Osterman)