Einstein's math may also describe faster-than-light velocities

Loading...

Although Einstein's theories suggest nothing can move faster than the speed of light, two scientists have extended his equations to show what would happen if faster-than-light travel were possible.

Despite an apparent prohibition on such travel by Einstein’s theory of special relativity, the scientists said the theory actually lends itself easily to a description of velocities that exceed the speed of light.

"We started thinking about it, and we think this is a very natural extension of Einstein's equations," said applied mathematician James Hill, who co-authored the new paper with his University of Adelaide, Australia, colleague Barry Cox. The paper was published Oct. 3 in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical and Physical Sciences.

Special relativity, proposed by Albert Einstein in 1905, showed how concepts like speed are all relative: A moving observer will measure the speed of an object to be different than a stationary observer will. Furthermore, relativity revealed the concept of time dilation, which says that the faster you go, the more time seems to slow down. Thus, the crew of a speeding spaceship might perceive their trip to another planet to take two weeks, while people left behind on Earth would observe their passage taking 20 years.

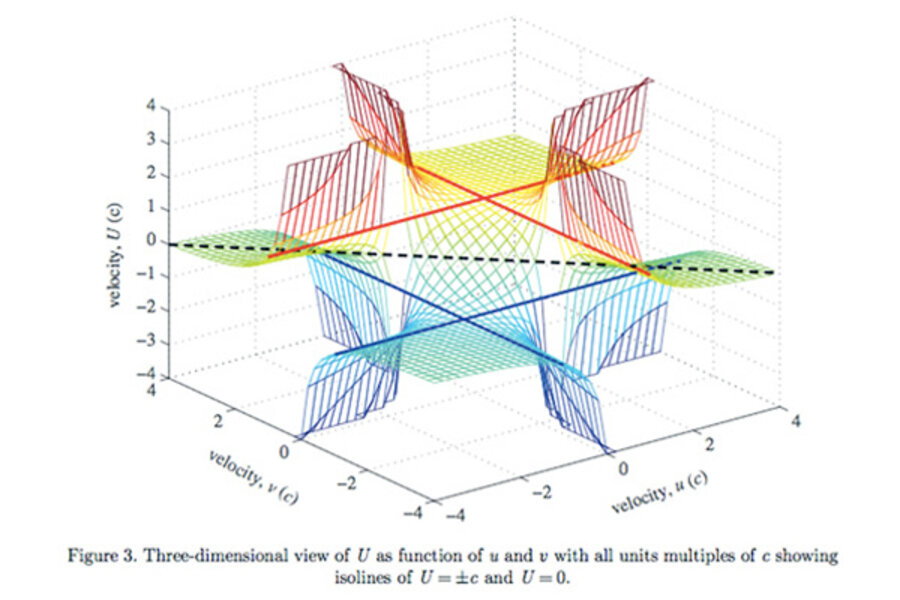

Yet special relativity breaks down if two people's relative velocity, the difference between their respective speeds, approaches the speed of light. Now, Hill and Cox have extended the theory to accommodate an infinite relative velocity. [Top 10 Implications of Faster-Than-Light Neutrinos]

Interestingly, neither the original Einstein equations, nor the new, extended theory can describe massive objects moving at the speed of light itself. Here, both sets of equations break down into mathematical singularities, where physical properties can't be defined.

"The actual business of going through the speed of light is not defined," Hill told LiveScience. "The theory we've come up with is simply for velocities greater than the speed of light."

In effect, the singularity divides the universe into two: a world where everything moves slower than the speed of light, and a world where everything moves faster. The laws of physics in these two realms could turn out to be quite different.

In some ways, the hidden world beyond the speed of light looks to be a strange one indeed. Hill and Cox's equations suggest, for example, that as a spaceship traveling at super-light speeds accelerated faster and faster, it would lose more and more mass, until at infinite velocity, its mass became zero.

"It's very suggestive that the whole game is different once you go faster than light," Hill said.

Despite the singularity, Hill is not ready to accept that the speed of light is an insurmountable wall. He compared it to crossing the sound barrier. Before Chuck Yeager became the first person to travel faster than the speed of sound in 1947, many experts questioned whether it could be done. Scientists worried that the plane would disintegrate, or the human body wouldn't survive. Neither turned out to be true.

Fears of crossing the light barrier may be similarly unfounded, Hill said.

"I think it's only a matter of time," he said. "Human ingenuity being what it is, it's going to happen, but maybe it will involve a transportation mechanism entirely different from anything presently envisaged."

Follow Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz or LiveScience @livescience. We're also onFacebook & Google+.