How many basic emotions do you have? It's written on your face, say scientists.

Loading...

Perhaps right now you're feeling a sense of sheepishness, solemnity, somberness, sangfroid, saudade, or schadenfreude. Or maybe you're one of those people capable of experiencing emotions that don't begin with the letter 'S.'

But whatever it is you happen to be feeling, your emotions will often make themselves known, however fleetingly, by contracting the muscles on your face, causing your mouth to smile or grimace, or your eyes to widen or narrow, or your brow to knit or furrow.

Psychologists have long thought that these complex emotions are composed of more basic, universal ones. Identifying exactly what these emotions are could aid everyone from forensic psychologists trying to determine the reliability of a witness to computer animators trying to get a character's reaction to look just right.

But what, exactly, are the primary colors of your emotional palette?

In the 4th century BC Aristotle came up with what he thought were the 14 irreducible emotions: Anger, Calm, Friendship, Enmity, Fear, Confidence, Shame, Shamelessness, Kindness, Pity, Indignation, Envy, Emulation, and Contempt.

Like many of Aristotle's ideas, this description remained largely unchallenged throughout the Middle Ages, until Europe's intellectuals began experiencing another emotion, namely, The Suspicion That Maybe Aristotle Shouldn't Always Have The Last Word On Everything.

This sentiment led, in a roundabout way, to Europe's scientific revolution, whose emphasis on experimentation and analysis inspired a 19th-century neurologist named Duchenne de Boulogne to set about poking people's faces with electrified wires.

As you might expect, the resulting muscle spasms produced a variety of grotesque facial contortions, which Duchenne generously termed the "gymnastics of the soul." They also revealed that different people tended to use the same facial muscles to produce the same expressions. Using the newly invented camera, Duchenne catalogued these expressions in his 1862 book, "The Mechanism of Human Physiognomy," which one of the world's first books to contain photographs. Human facial muscles, Duchenne wrote, were designed to convey even the most fleeting of emotions, speaking a language that is "universal and immutable."

Duchenne is perhaps best known today for identifying an expression of genuine positive emotion, in which the corners of the eyes and the mouth crinkle. Unlike the polite "Pan-Am" smile ("Thanks for flying with us! Buh-bye!"), the "Duchenne smile" cannot readily be faked.

Duchenne's work greatly influenced Charles Darwin's research into facial expressions and emotions. In his 1872 book, "Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals," another milestone in the history of photography, Darwin proposed that effectively using one's face to communicate emotions conferred an evolutionary advantage, and he hypothesized that some facial expressions and their corresponding emotions, were universal to humans, and – significantly – their animal relatives.

Darwin was also one of the first to propose what is today called the facial feedback hypothesis. Put on a happy face, the hypothesis goes, and before long you will start genuinely feeling happier. "The free expression by outward signs of an emotion intensifies it," wrote Darwin.

In the 20th century, the American psychologist Paul Ekman expanded on Darwin's theories of emotion, methodically measuring and coding different facial expressions across cultures. In 1978, Dr. Ekman, who recently served as a scientific adviser to the Fox crime drama "Lie to Me," developed a detailed taxonomy of facial expressions. Called the Facial Action Coding System (FACS), Ekman's system measures the movements of all of the human face's 42 muscles, as well as movements of the head, eyes, and tongue.

Ekman found six universal facial expressions, ones that were the same for people all over the world, from the highlands of Papua New Guinea to the bowling alleys of Cherry Hill, N.J.. He identified their corresponding emotions as Happiness, Sadness, Fear, Surprise, Anger, and Disgust. (He later added to his schema a seventh emotion: Contempt.)

Happiness, for instance, is expressed with pushed up cheeks, widened eyes, raised eyebrows, wrinkled "crow's feet" around the eyes, and a gaping mouth. Disgust is expressed with a wrinkled nose, a turned-down lower lip, a raised upper lip, protruding lips, and an open mouth. And so on.

These expressions are thought to have arisen from basic survival mechanisms. Widening the eyes in fear, for instance, might represent an effort to take in more visual information about the environment. And wrinkling the nose in disgust impedes breathing, possibly limiting the intake of toxins or pathogens.

But are Ekman's universal emotions really universal? A 2009 study using FACS-coded faces found that East Asian observers were less able to distinguish between fear and disgust and between surprise and anger than their Western Caucasian counterparts. The East Asians, the study reported, tended to fixate more on the eyes, while the Western Caucasians tended to look at the whole face. The results, reported the study's authors, "question the universality of human facial expressions of emotion, highlighting their true complexity, with critical consequences for cross-cultural communication and globalization."

That study's lead author, University of Glasgow psychologist Rachael Jack, continued to question Ekman's model. Most of the research, she noticed, relied on still images of people's facial expressions. But that's not how it works in the real world.

"Facial expressions are dynamic," Dr. Jack told the monitor in a phone interview. "As social beings, we're decoding dynamic signals over time."

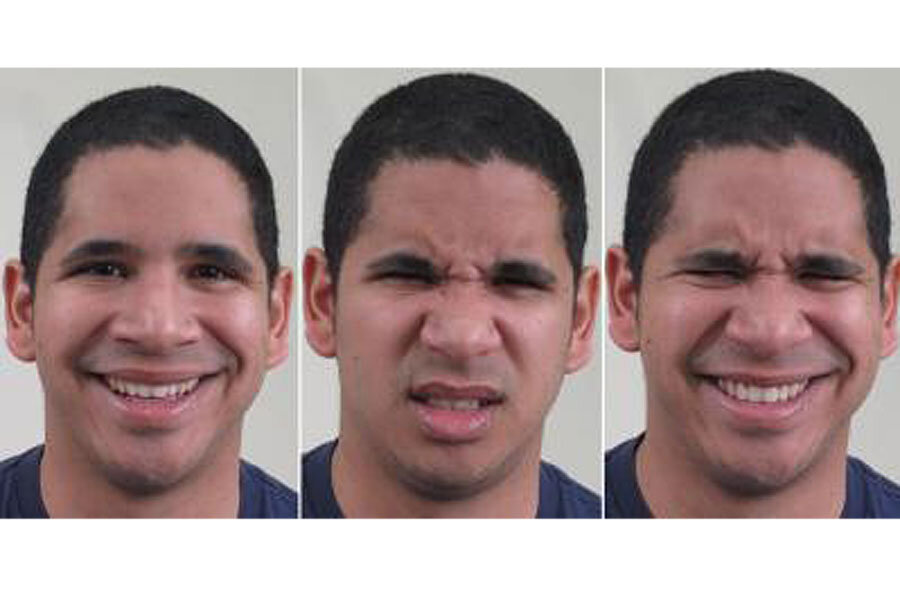

To test how people responded to facial expressions over time, Jack and her colleagues enlisted people who had been specially trained to individually flex facial muscles (if you can raise each eyebrow individually and sneer with both sides of your mouth, you just might have a marketable skill). These face wizards were filmed in three dimensions and their mugs compiled into an animated virtual face that could be programmed to display various expressions. The team then showed these expressions to volunteers and asked them what they saw.

This time, Jack found that her subjects were initially confused between expressions of fear and surprise and between those of anger and disgust. As the virtual face began making each expression, it showed signs of both. "Early in the time course, disgust and anger both show the nose wrinkle," says Jack. And "fear and surprise show the same signal." It is only later on, Jack found, that these expressions resolve themselves into more socially specific signals.

This makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint, says Jack. When we are faced with a potentially threatening stimulus, our first imperative is biologically basic – for instance to take in more information or to prevent the intake of toxins. Only after do we concern ourselves with communicating our more complex emotions to others.

Jack's research suggests that our faces express just four, not six, psychologically irreducible emotions: Fear-Surprise, Anger-Disgust, Happiness, and Sadness). But none of this is to suggest, as many news sources claimed, that humans have only four feelings. "Nobody in their right mind would say there are only four emotions," says Jack. "That simply isn't true. Human beings have incredibly complex emotions."

Ohio State University cognitive scientist Aleix Martinez has a similar respect for the complexity of human feelings. In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences he describes how he and his team applied Ekman's coding system to photos of 230 volunteers making facial expressions to develop a way for computers to recognize 21 distinct facial expressions, including those that express seemingly contradictory emotions such as "happy disgust." Those 21 expressions include Eckman's original six, as well as 17 blends of those primary emotional colors.

Martinez says that he hopes that this method will help researchers more accurately determine how emotions are correlated with states in the brain. He also says that this technology could help assist people suffering from social deficits, for instance traumatized veterans who may be more attuned to expressions of anger and fear than to happiness. This method could also help with the development of companion robots who can assist the elderly with a more nuanced understanding of their feelings.

"I just couldn't believe there were only six emotions," said Dr. Martinez, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at OSU. "Something struck me. From these six categories, there was just one positive emotion: happiness. There was one neutral emotion: surprise. And there were four negative emotions. That just didn't make any sense to me. We are negative people, but we are not that negative."