NASA's Mars 2020 rover: tools it will use to hunt for ancient microbial life

Loading...

Thanks to NASA's Mars rover Curiosity, scientists have established that at least one location on the red planet hosted an environment that would have been hospitable to life.

Now, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration is set to hunt for evidence of life on Mars – in this case, ancient microbial life. This new rover mission, dubbed Mars 2020, also will help lay the foundation for the eventual arrival of extant life – astronauts.

On Thursday, NASA officials announced that the agency has agreed to support a suite of seven instruments for the mission, which is likely to cost about $1.9 billion.

In addition to souped-up tools for analyzing rocks for potential signatures of past biological activity, the Mars 2020 rover will carry hardware designed to draw oxygen from the planet's atmosphere, which is dominated by carbon dioxide. (Locally generated oxygen not only would help keep astronauts alive, but also would help fuel rocket motors for the trip back to Earth.)

The rover also will carry tools to cache intriguing rock samples it finds for later return to Earth for more-detailed study, although no sample-return mission is in the queue.

Mars 2020 represents "our next big leap in the exploration of Mars," said John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for the agency's Science Mission Directorate, during a briefing Thursday. "It's amazing to think about the fact that Curiosity has determined that Mars once had a habitable environment. The science behind the Mars 2020 rover is really going to extend that" as it looks for potential signatures of biological activity locked up in Martian rocks.

Mars 2020 takes advantage of hardware and expertise developed for Curiosity's highly successful mission – one that's still under way. The new mission's projected cost is about $600 million less than Curiosity's price tag, thanks to a demonstrated design, some spare parts, and a proven landing system (despite Curiosity’s landing having been "seven minutes of terror").

Still, the new rover will have some updates, NASA officials say: redesigned wheels to avoid problems that Curiosity has had; an ability to move a bit faster than Curiosity; and an ability to land with lower uncertainties about its exact touchdown spot, a trait that will allow it to land in places that past missions had to avoid, says Jim Green, who heads NASA's Planetary Science Division.

Indeed, the science team has been reviewing 30 potential landing sites, 10 of which are intriguing enough to warrant additional scrutiny by orbiters currently at Mars.

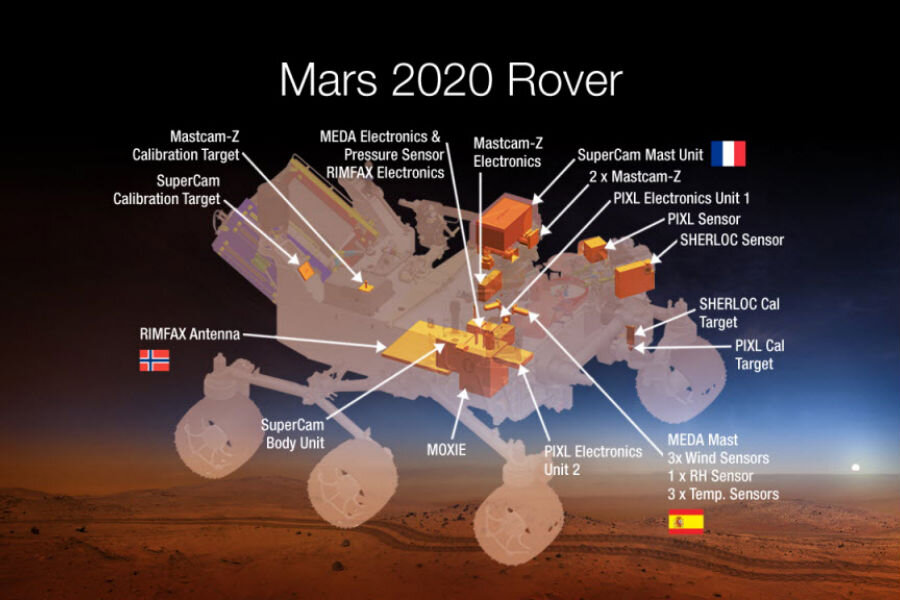

Like Curiosity, the new rover will have cameras and chemical-analysis systems mounted atop its mast. One camera will have twin zoom lenses that will allow it to take 3-D images of its surroundings – a trait that will make planning the rover's route easier, even as the camera also provides data on the minerals in the rocks it sees.

A second camera is an enhanced version of Curiosity's ChemCam: It supports three spectrometers, which will analyze the effects of a laser zapping rocks. In addition, it will make images that can reveal minerals and organic material on sections of rock as small as the width of a human hair.

The chassis hosts three instruments: a weather station that also will monitor dust conditions and how they change the environment around the rover; the CO2-to-oxygen separator; and radar that is capable of peering more than 1,000 feet below the surface to trace geological formations but that also is capable of detecting subsurface ice or ground water.

The rover's arm will host two complementary spectrometers that provide information on the chemicals and minerals in rocks at scales comparable to the size of microbes.

"To look for signs of ancient microbial life, then we really need to be able to investigate rocks at microbial scales," said Abigail Allwood, an astrobiologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the lead scientist for an instrument dubbed PIXL, one of the arm's two spectrometers.

In addition, the arm will carry a drill designed to take core samples of rock, rather than generate powdered samples for analysis on site. Assuming the samples it takes wind up back on Earth, having a well-preserved layered core can convey far more information about the changing environment than powder.

Indeed, all the tools designed to analyze the composition of rocks aboard Mars 2020 appear to use nondestructive techniques, since the aim is to first spot promising samples from afar, sniff them up close, and then bring them back alive – figuratively speaking.

While the Mars 2020 rover's overall mass is expected to match Curiosity's, the mass of the science packages will be roughly 40 percent lower than the science package Curiosity carries.

"We know from Curiosity, which is sitting in Gale Crater, that environment in the past was habitable – about 3.5 billion years ago," Dr. Green said at the briefing. That's when life was beginning to gain a foothold on Earth.

The hope, he says, is to find additional signs of ancient life on Mars, adding, "that would be indeed a real revelation."