Why scientists are so fascinated with how the turtle got its shell

Loading...

Hundreds of millions of years ago, before even the dinosaurs walked the Earth, the distant ancestors of turtles wobbled along the shores of a vast supercontinent. They were small and lizard-like, with up to 40 teeth and a 4-inch tail, but they were missing one defining feature: a shell.

The turtle shell has long been a source of fascination for researchers. The only other vertebrates who have a shell like it are tortoises and terrapins, which came along later. But the feature has remained so enigmatic that not even Rudyard Kipling could explain its existence in a "Just So" children's story.

"The question of the origin of the turtle shell is one of the longest standing controversies in understanding the evolutionary history of backboned animals," says Hans-Dieter Sues, a curator at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.

The fusion of rib bones, shoulder bones, and vertebrae to form a shell on the outside of their bodies make turtles unique, and how it developed in prehistoric times has puzzled biologists for more than 200 years, writes the Smithsonian Institute.

"Turtle shells are kind of a unique structure," Dr. Sues adds. "People have for a long time wondered how they came about."

Until today, the oldest known possible turtle ancestor was a 220-million-year-old specimen discovered in China, dubbed Odontochelys, which featured a partly-formed shell and other turtle-like features. Prior to that discovery in 2008, scientists had uncovered remains of a 260-million-year-old animal in South Africa known as Eunotosaurus, hypothesized to be an even older turtle ancestor, featuring wide and flat ribs but no distinct shell-like features. But with such a large temporal gap between the Odontochelys and the Eunotosaurus, researchers couldn't be sure the two animals were related.

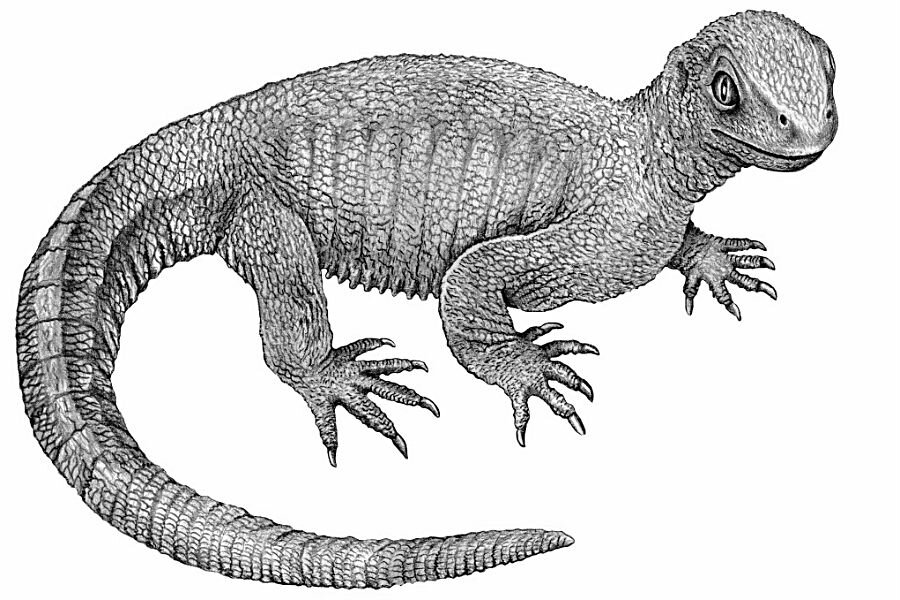

Sues has been investigating this mystery, however, studying a fossil specimen from the mid-Triassic Period. He is the co-author of a paper published in the journal Nature making the case that the Pappochelys – meaning "grandfather turtle" in Greek – could be the important missing link between the the Odontochelys and Eunotosaurus that researchers have been looking for.

At roughly 240-million-years-old, the animal fits neatly between the two other species chronologically, and its physical features also make it likely that it is a descendant of Eunotosaurus and an ancestor the modern turtle.

The older, South African fossil showed strong, wide ribs but no distinct shell. The younger, Chinese fossil showed the same rib structure but also a shell of hardened, fused bone on its belly. The Pappochelys – a small animal at roughly 8 inches long – seems to be a less-developed version of the Chinese fossil: similarly widened ribs and a breastplate abdominal bones that were just starting to fuse and ossify.

Scientists believe the breastplate and ribs later expanded and fused together to completely enclose the animal in its famous shell around 210 million years ago. The ribs, meanwhile, provided not only protection for the animal but also a "bone ballast," which helped the animal control its buoyancy.

"We now have a beautiful series of intermediate stages to trace the origin of this very peculiar structure, the turtle shell," says Sues.

The Pappochelys fossil was disocvered in a limestone quarry near Stuttgart, Germany, about 8,000 miles from South Africa and almost 7,000 miles from southwest China, where the Odontochelys and Eunotosaurus fossils were found.

Sues says that the vast distances between them doesn't mean the three species aren't related to each other, because in the millenniums over which they were evolving, all the continents were linked together into a single giant landmass known as Pangaea.

An alternate theory suggests that turtle shells developed along the lines of dinosaurs and modern reptiles like crocodiles, through the fusion of bony armor plates. Instead, this new evidence suggests it formed through the fusion and expansion of chest and rib bones.

Tyler Lyson, a curator at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science, studies turtle evolution as was one of the first researchers to argue that the 260-million-year-old fossil from South Africa was a turtle ancestor.

In an interview with NPR, Dr. Lyson said that the German fossil adds to a comprehensive fossil collection that can now "tell this really cohesive story on the origin of the turtle body plan."

The discovery also provides greater weight to the theory that turtles evolved from more modern reptiles, rather than ancient reptiles like dinosaurs and birds. The Pappochelys skull features two openings behind the eye sockets often seen in almost all modern reptiles – extra space designed to help jaw muscles develop.

"Our animal has two openings, just like we see in lizards," says Sues.

"[We] thought turtles had branched off way, way down in time from other reptiles," he adds. "[This] proves from the fossil record that turtles are … part of a lineage that flows through all modern reptiles."