Rosetta spacecraft detects molecular oxygen on comet

Loading...

The Rosetta spacecraft has detected molecular oxygen in the gas streaming off comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, a curious finding that has scientists rethinking the ingredients that were present in the early solar system.

What's mystifying astronomers about the new find is why the oxygen wasn't annihilated during the solar system's formation. Molecular oxygen is extremely reactive with hydrogen, which was swirling in abundance as the sun and planets were created. Current solar system models suggest the molecular oxygen should have disappeared by the time 67P was created, about 4.6 billion years ago.

"It was a big surprise to actually detect the O2 [oxygen]," Andre Bieler, a research fellow at the University of Michigan who co-led the study, said in a media briefing held by the journal Nature, where the new research was published. [Photos: Europe's Rosetta Comet Mission in Pictures]

While the study suggests solar system modelling may need revision, Bieler and co-author Kathrin Altwegg, a space scientist at the University of Bern — both of whom are cometary scientists and not modeling experts — said they could not speculate too much on what, exactly, would change about those models.

Meanwhile, the scientists said they are trying to find molecular oxygen in the 1986 Giotto spacecraft observations of Halley's Comet, the only other comet to get a close-up visit from a spacecraft. The spectral lines of oxygen are too faint to be seen from Earth. This means that even though molecular oxygen may be common in other comets, there is no way yet to confirm that theory.

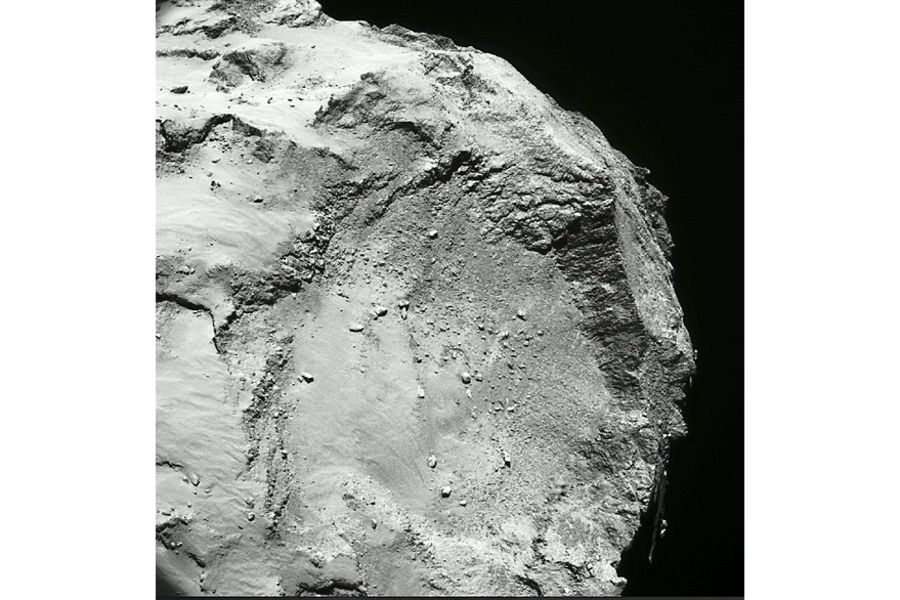

Rosetta has spent more than a year following Comet 67P as it traveled around the sun in a loop that came close to Mars' orbit, then whizzed back to the outer solar system. In that time, Rosetta has detected many elements in the comet's coma (the cloud of gas around the rocky nucleus), such as water, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. These elements are common to other comets that scientists have observed.

But molecular oxygen was not expected at all, the scientists said. Rosetta's mass spectrometer, ROSINA-DFMS, detected it over six months between September 2014 and March 2015. The scientists spent months making sure that the oxygen was not an instrument glitch.

They observed that the oxygen was denser when the spacecraft was close to the comet and less dense when the spacecraft was farther away. The oxygen also seemed to "follow" the comet, and remained in constant quantities even as 67P shed its outer layers to the sun. With the detection of it confirmed, the scientists then asked themselves how it got there in the first place.

Dueling theories

There are two leading theories as to how the oxygen got into the comet. Perhaps the oxygen, as a gas, dissolved or "froze out" onto the icy grains that eventually came together to construct the comet.

The problem with that theory is that gaseous molecular oxygen has only been found a couple of times outside of the solar system (the researchers did not have details as to where). This hints that this kind of gas must be rare in the solar system. Also, chemistry suggests that it should transform into water ice rather than staying as molecular oxygen.

Alternatively, maybe water ice on 67P's surface broke up as energetic or radioactive particles bombarded the regolith (dust covering the surface of the comet). In several steps, the water — made up of hydrogen and oxygen atoms — could break up into molecular oxygen, which would then "be incorporated into voids that are also created in the ice," Bieler said.

This sort of process could have created the oxygen molecules observed near the moons of Jupiter and Saturn. In this case, the moons would have been struck by high-energy particles from the gas giant planets, which have massive radioactive fields surrounding them, the scientists said. 67P, however, lacks this sort of immediate, nearby source for radiation.

However the molecular oxygen got into the comet, the authors suggest that it must have been there before the solar system was formed about 4.5 billion years ago. Perhaps high-energy particles bombarded the birthplace of our sun — known as a dark nebulae — and split the water present in that nebula into oxygen and hydrogen.

This is supported by measurements of 67P suggesting that much of the material inside of it predates the solar system, and further, that its composition is similar to dark nebulae.

A paper based on the research was published today (Oct. 28) in Nature.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

- Eerie Comet Landscape Revealed by Rosetta Spacecraft Photos

- Philae Comet Landing: Big Discoveries About Comet 67P (Infographic)

- 5 Amazing Facts about Europe's Comet-Chasing Rosetta Probe

Copyright 2015 SPACE.com, a Purch company. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.