How did gullies on Mars get that way? Dry ice, say scientists

Loading...

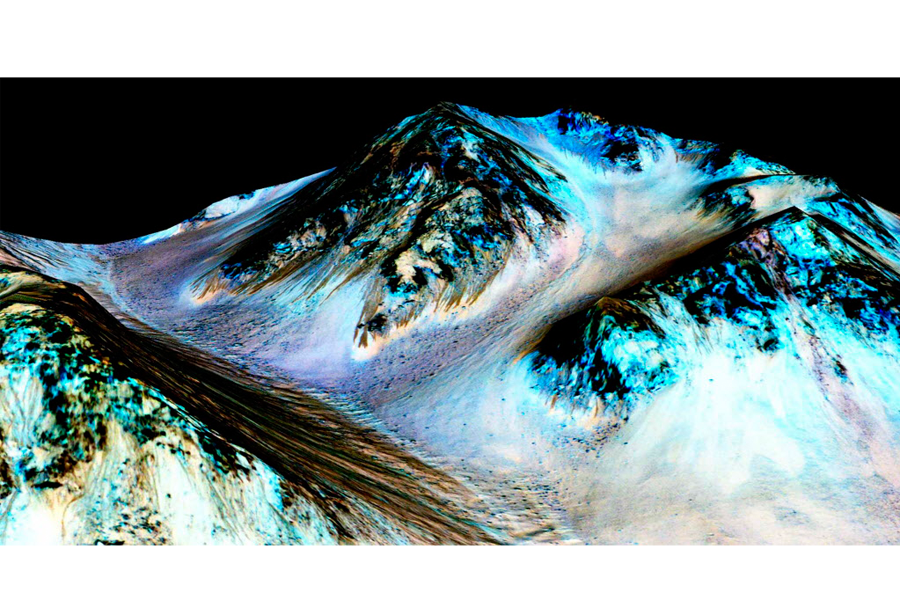

We know, thanks to observations from NASA’s Curiosity rover, that Mars once held water. But how did the Red Planet get those signature rivets and gullies on its surface?

A new study, recently published in Nature Geoscience, may have the answer to that question. The researchers propose that seasonal layers of CO2 frost, not water, play an ongoing role in the formation of the gullies that crisscross Mars’s surface.

“CO2 frost covers the Martian poles and mid-latitudes every winter,” Dr. Colin Dundas, of the US Geological Survey, wrote in an accompanying News & Views article. “Near the poles, this seasonal cap is around [three feet] thick, and thins towards the mid-latitudes. The distribution of frost correlates with the regions where gullies are most prominent.”

The scientists, Drs. Cedric Pilorget and Francois Forget, used a thermal model to make their projections. They examined two layers, the defrosting CO2 layer on the surface and the trapped CO2 gas underneath, to determine that when the pressure of the trapped gas builds up, it causes instability in the layer of defrosting ice and, ultimately, flows of CO2 ice that are moved along by rivulets of CO2 gas.

The scientists used their model to examine multiple different scenarios across a Martian season, including temperature and gully slope. They started their examination with the Russell crater megadune, one of the first Martian craters where scientists have previously noted gullies being formed.

The scientists observed that gully formation begins when, during a Martian winter, the sun begins to melt the CO2 ice, causing particles to trickle down to the layer of CO2 gas underneath. The pressure on the CO2 gas increases as the melting accelerates, and as the gas moves upward and outward, it carries with it particles of soil and tracks of melted ice that eventually form the Red Planet’s gullies.

Because gullies continue to be formed even today on the Martian surface, at a time when there is no more water naturally occurring on the Red Planet, the scientists question the possibility of a scenario in which ancient water played a role in gully formation.

“When dealing with other worlds, we must take care to remember that unfamiliar processes are possible and even likely in alien environments,” Dr. Dundas wrote. “The Martian gullies may look like terrestrial landforms shaped by liquid water, but it may be CO2 , not water, that is the culprit.”

If these gullies were formed by dry ice, as Drs. Pilorget and Forget suggest, and not water, it may provide more clues to the still-evolving mystery of the surface composition of Mars – a mystery that the Curiosity rover is on the Red Planet attempting to solve. The Curiosity rover has been examining Martian silica for what information it may hold about the origin of Martian water. It has also been traversing Mars's sand dunes, which look very different from the ones on Earth, to study the history of Martian dune formation.