How the Namib Desert beetle could help stop frost on airplanes

Loading...

A desert beetle taught scientists how to prevent frost on airplanes, coils, and windshields.

A team of scientists with the Virginia Polytechnic Institute (Virginia Tech) has discovered a method for controlling and preventing frost, according to a study published in Scientific Reports, an online journal run by Nature. The method works around the combination of a specific pattern overlaid on top of a water-resistant surface. The team believes that by scaling up tests, the method would be conducive for use on larger commercial objects, like airplanes.

The inspiration for the effective frost prevention method came from an insect that lives in an environment where frost is rarely a problem. Scientists based their method off the shell of the beetle.

The lessons learned from the Namib Desert beetle are the latest in a trend of nature-inspired scientific breakthroughs.

"I appreciate the irony of how an insect that lives in a hot, dry desert inspired us to make a discovery about frost," said Jonathan Boreyko, an assistant professor of Biomedical Engineering and Mechanics in the Virginia Tech College of Engineering, in the press release for the study. "The main takeaway from the Desert Beetle is we can control where dew drops grow."

The Namib Desert beetle lives in the deserts of southwest Africa, where water is scarce. The beetle is able to collect airborne water through unique properties on its shell. Specialized bumps working in tandem with the shell’s smooth surface allows water droplets to form and run to the beetle’s mouth, according to Modern Reader.

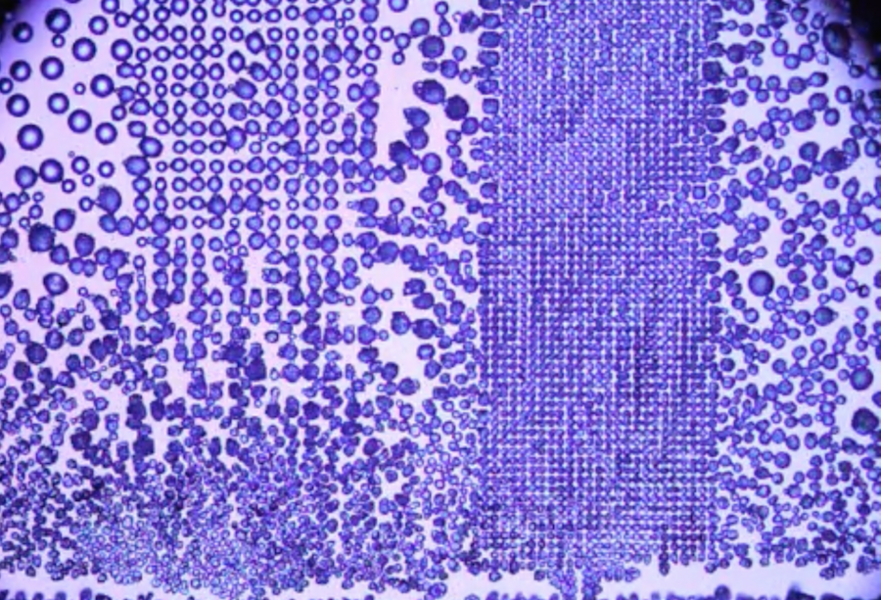

Scientists viewed the unique patterns of the bumps on the beetle’s shell and replicated them onto a silicon wafer, a process known as photolithography. The chemical pattern attracts water droplets, while the surface of the material repels it. The result keeps water droplets separated and running, which slows or entirely prevents frost from growing.

The scientists noted their success in the introduction of their study:

Here, we demonstrate that chemical patterns can be used to tune the spatial distribution of supercooled condensation and subsequently control the geometry and speed of inter-droplet frost growth…. For the first time, inter-droplet ice bridging could be completely halted by utilizing sufficiently sparse hydrophilic patterns and by quickly triggering a freezing event near the patterned condensation.

According to the press release, the scientists have successfully tested the method on a surface about a centimeter in size, but say it can be scaled up for commercial use.

"Keeping things dry requires huge energy expenditures," said C. Patrick Collier, a co-author of the study, in the press release. "That's why we are paying more attention to ways to control water condensation and freezing. It could result in huge cost savings."

This not the first time the Namib Desert beetle has offered a novel solution to a human problem. In 2012, a US startup company based their concept for a self-filling water bottle around the beetle’s natural ability to distill water from the air. Similar “nature-inspired” solutions can be seen in everyday and future technology.

In 2009, Qualcomm MEMS Technologies created the first full-color e-reader screen based on technology inspired by butterfly wings, according to Livescience. In 2011, a team of researchers in Japan created a film to help solar panels capture more energy from the sun that was inspired by moth eyes. Recently, in 2015, a group of scientists created a new sensor for small drones that was discovered from studying insect eyes.

The growing trend of nature-inspired solution have led to the opening of organizations like the Centre for Bioinspiration in California and the Biomimicry Institute in Montana, among others.