Mercury transits the sun: How to watch it like an ancient astronomer

Loading...

On Monday, Mercury will make a rare trip across the surface of the sun, making it visible from Earth for several hours.

The unusual event, which occurs only about 13 times each century, has held a fascination for astronomers dating back to the Renaissance.

This year's transit will occur between 7:12 a.m. and 2:42 p.m. Eastern time, meaning most of the planet will get to see at least part of it. People in Europe and most of the Americas will be able to see the whole thing, as geoscientist David Rothery writes in The Conversation.

NASA and several observatories will be posting a live stream online, and local astronomy clubs with a telescope equipped with a solar filter for safe viewing are hosting events around the world.

But there's also a simpler way to view the transit without a specialized telescope. As a bonus, it's informed by the history of astronomy.

In 1631, the French philosopher and astronomer Pierre Gassendi became the first person to observe a planet passing before a star, when he viewed Mercury's transit using a pinhole camera (or in Latin, camera obscura), which involved a telescope and a darkened room where images were projected onto a piece of paper. He was also the first person to observe a planet passing before a star.

But unlike Mr. Gassendi's device, which required an assistant stationed in a room below to measure the Sun's altitude with a large quadrant every time Gassendi stamped his foot, making a homemade version out of cardboard is relatively simple.

As directions created by scientists at the Polish Academy of Sciences and the University of Wrocław explain, it's then possible to look at the sun by viewing the projected image:

If we put an opaque diaphragm with a small hole on the way of the light rays, then different light rays from each single piece of the observed object (e.g. the solar disc) are cast on different parts of the screen that is placed behind the diaphragm. In this way we get a real, diminished, inverted, and relatively clear image of the observed object

...Because each picture element is created by a separate light beam, the image created by the camera obscura has infinite depth of field (which is always sharp!) and shows a complete lack of distortion. If the observed object is the Sun with Venus passing in front of it, on the screen we get a clear picture of the solar disc with the black dot of the planet.

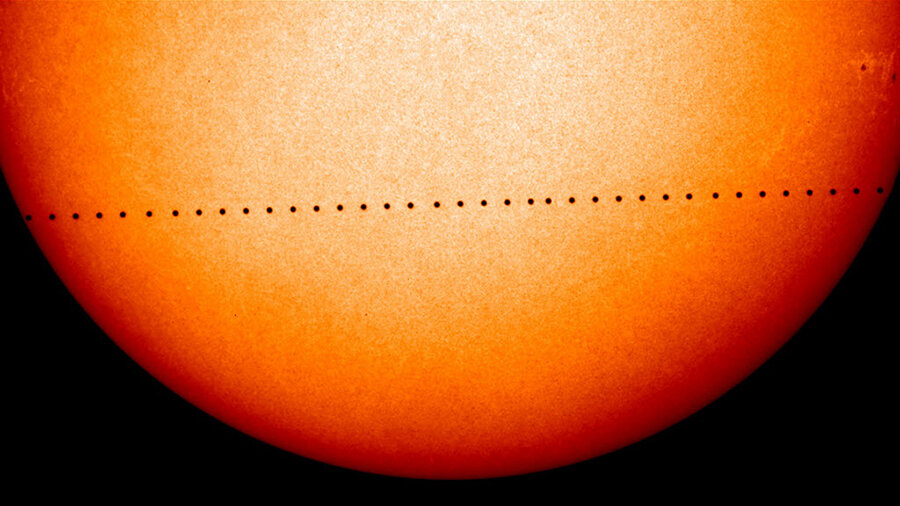

A transit, which is visible as a tiny black dot against the surface of the sun, occurs because Mercury orbits the sun closer than Earth does, with an orbit that is slightly tilted — about 7 degrees — compared to our own.

A transit occurs when both Mercury and Earth are close to the points where the planes of the two planets' orbits intersect. Because Mercury's orbital period is a much brisker 88 days, compared to that of Earth, the planet will pass directly between Earth and the sun only in early May or November, notes Dr. Rothery. The last one occurred in 2006.

Transits have several uses for scientists, including helping them identify exoplanets, or those that orbit a star other than the sun. More than a thousand have been identified so far during a transit, according to NASA. Previous transits have also been used to help determine the diameter of the sun.

The unusual nature of the event is also a draw, notes Slate's Phil Plait.

"I've seen a couple of Mercury transits (and two Venus transits, too)," he writes, "and it's decidedly weird to see that tiny, perfect little circle slowly move across the Sun's face. It connects you with the cycles of the Universe, shows you how wonderful and rare and grand such events can be."