Water didn't carve Mars' gullies. What did?

Loading...

Mars and its atmosphere may have had a strikingly Earthlike past in some ways, but NASA announced Friday that unlike Earth, some of Mars’ geological features are not formed by flowing water.

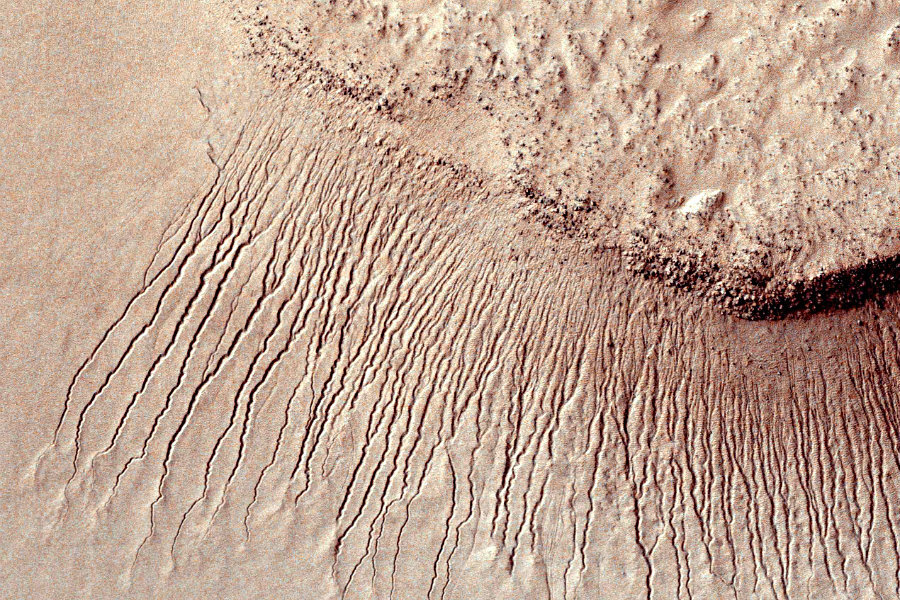

Scientists have long been aware of the presence of gullies on Mars. On Earth, similar looking gullies would have been carved by rainwater runoff, and for some time, scientists theorized that they could indeed have been created by liquid water. Recent tests, however, indicate that liquid water is not responsible for Mars’ gullies. But what is?

“Mars is not a cookie-cutter planet of water or no water,” lead author Jorge Nuñez, a planetary scientist at Johns Hopkins, told the Los Angeles Times, “and it just goes on to show the complexity that there is on Mars. And obviously there’s still a lot that we don’t understand – yet.”

Researchers used the Mars Orbiter's Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM), as well as its High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, to examine high resolution images of 100 sites on Mars.

There was no evidence in the photos for the presence of liquid water or its byproducts, according to NASA. And when scientists did see things, including clays, that would indicate the presence of liquid water, they provided evidence for a past Mars with liquid water on its surface, rather than at present.

“On Earth and on Mars, we know that the presence of phyllosilicates – clays – or other hydrated minerals indicates formation in liquid water," Dr. Núñez said in a NASA press release. "When we did see them, they were erosional debris from ancient rocks, exposed and transported downslope, rather than altered in more recent flowing water. These gullies are carving into the terrain and exposing clays that likely formed billions of years ago when liquid water was more stable on the Martian surface."

Scientists have since turned to other possible explanations for the presence of Mars’ gullies, which are common particularly in areas near the planet’s poles. One other primary suspect in the mystery of the gullies is the freezing and thawing of carbon dioxide frost.

Researchers who support the carbon dioxide frost theory have created computer modeling to support their idea. This latest study provides even more evidence that they may be right, by eliminating the possibility that liquid water carved the gullies.

So is there water on Mars? Certainly not in the form that we experience it on Earth, where flowing water is abundant enough to carve gullies and shape geological features. Yet, there is still evidence that water existed on Mars at one point.

Not only do the presence of ancient clays indicate that there was likely liquid water on the red planet at some point, another of Mars’ geological features, recurring slope lineae (RSL), also give evidence for water in some form. These RSL are dark stripes that change depending on the seasons, and could be caused by very salty water, as evidenced by the presence of hydrated salt.

This latest study was published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.