Why is the ESA's Schiaparelli Mars lander so special?

Loading...

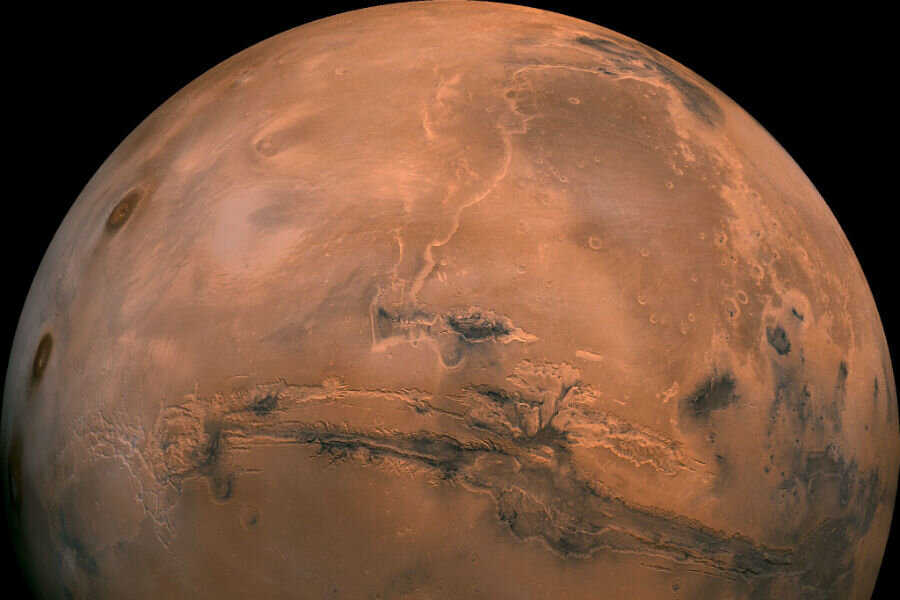

The next phases of ExoMars, a mission to the Red Planet jointly conducted by the European Space Agency and Russia’s Roscosmos are almost complete.

On October 19th, if everything goes according to plan, the agencies will land a demonstration craft on Mars using cutting-edge technology and techniques. The Schiaparelli lander, essentially a test run for the ExoMars rover set to launch in 2020, aims to correct issues with the ESA's last Martian probe, the Britain-designed Beagle 2, which was unable to properly deploy after a rough landing in December 2003.

Schiaparelli will have to face the perils of an autonomous landing on a planet notorious for defeating probes, with its thin atmosphere making it difficult to slow decent, compounded by the impossibility of direct input from Earth because of the minimum 26-minute round-trip delay in signals between the craft and mission control. But the scientists participating in the project say the probe is ready.

"The EDM [Landing Demonstrator Module] is Europe's first try at landing on Mars, and as landing systems go, it is pretty ambitious," Jorge Vago, ESA-ExoMars Project Scientist, told Sky & Telescope. "Schiaparelli incorporates a sophisticated Doppler radar to measure distance to the ground and speed over the surface. The information is used to command the pulsed hydrazine engines, which are organized in three clusters of three motors each."

Essentially, Schiaparelli will be launched with a traditional heat shield and parachute combo, but the thin atmosphere will not be enough to slow the EDM down enough for a safe landing with those methods. Once the parachute slows the descent as much as it can, the hydrazine rockets will slow it the rest of the way before cutting out two meters from the surface. From there, the probe will drop, with a crushable layer protecting the rest of the probe from harm.

The tricky part will be initiating all of the commands for the landing, including parachute deployment, heat shield ejecting, and so on, without direct contact from ESA's mission control in Darmstadt, Germany. For this, command sequences were uploaded in advance to activate the landing sequence far in advance of the October 19th touchdown.

"Uploading the command sequences is a milestone that was achieved following a great deal of intense cooperation between the mission control team and industry specialists," said Orbiter flight director Michel Denis in a statement. These pre-uploaded sequences will form the most direct input mission control has over the spacecraft for its decent.

If all goes according to plan, Schiaparelli will deploy some scientific equipment after landing but will operate only for a few days. The main goal of the EDM is to test the system for the deployment of a full rover that the agency hopes will operate for two years after it touches down on the Red Planet in the final phase of the ExoMars mission, which ultimately hopes to determine whether life ever existed on Mars, according to the ESA's website.

Schiaparelli is also being carried by a "mothership," the Trace Gas Orbiter, which will remain in orbit around the planet for seven years, searching out rare gases like methane. Mars' thin atmosphere means that methane soon vanishes from the surface.

But despite methane's lack of longevity, the gas has been detected on Mars before. On Earth, the primary source of methane is living microbes, though Mars' methane could come from some geological phenomenon.

"I am not sure we will ever be in a position to have a smoking gun, and say 'for sure, it is this,'" Dr. Vago told the BBC in March. "But little by little, as the mission progresses, we will get better at focusing our hypotheses and what the explanations might be."

As the probes approach Mars, the planet is beginning to kick up widespread dust storms across its surface. As the Monitor previously reported, it is possible that these storms could coalesce into a global dust storm by the end of the month, possibly interfering with rovers currently on the Martian surface.

"We always knew we could arrive in a dust storm and Schiaparelli was designed with that possibility in mind," Vago told the BBC. "And from the point of view of getting data on the electrification of dusty atmospheres, it could be very nice."