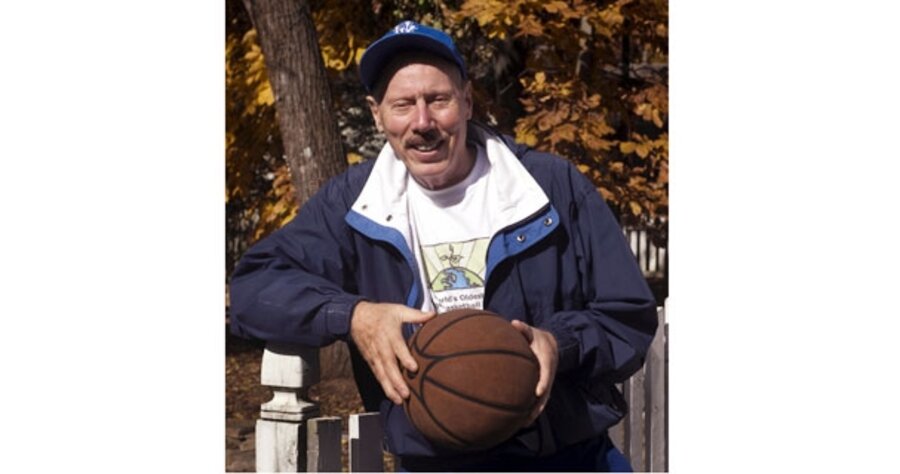

Ken Mink plays college basketball ... at age 73

Loading...

| Knoxville, Tenn.

The gray Cape Cod is easy to overlook on this quiet street in Knoxville, Tenn. No team pennants hang in the windows, no collegiate flags wave in the breeze. The parlor is surprisingly devoid of sports paraphernalia as well.

Paintings adorn the walls, and an eclectic mixture of books lines the bookshelves. There’s a mounted bass above the fireplace, and a cowhide rug covers the floor. If you ask, Ken Mink will show you the modest display of basketball medals he’s received. Otherwise, he won’t mention them at all.

This isn’t your typical college athlete’s home, but then, Mr. Mink isn’t your average basketball player. He’s climbed the Matterhorn. Parasailed over the Caribbean. Water-skied in Jamaica. And this fall, at age 73, he became what may be the world’s oldest college basketball player, joining Roane State Community College as a shooting guard and shattering stereotypes in a sport where youth is everything and players over the age of 25 are anomalies.

But Mink’s not looking to break records. He says he’s seeking redemption, attempting to fulfill a dream he’d abandoned and forgive a betrayal he can’t forget.

He left college in 1956 believing he’d never touch sneakers to hardwood again. Now he’s running suicide sprints, practicing free throws, lifting weights, and trading passes with players half a century younger.

Last fall, joining a college basketball team at his age seemed as likely as lapping Michael Phelps in the pool. He’d considered returning to school in his 20s, but by then he had a family. He played ball with his three children, but as the years passed, he thought less and less about joining a team again.

While shooting hoops in his neighbor’s driveway not long ago, though, he noticed something remarkable – he was nailing every shot.

“He said, ‘I’ve still got it!” his wife, Emilia, recalls. “And I said, ‘Got what?’ I didn’t take him that seriously, but then a week later, he told me he’d contacted all these colleges.”

Mink wrote to eight schools, knowing it was the longest shot he’d ever taken. Weeks passed. No one replied, not even to say, “You’ve got to be kidding.” Then coach Randy Nesbit called from a small college in Harriman, Tenn., 35 miles away. Mr. Nesbit was willing to give Mink a chance. Most of all, Nesbit was intrigued: He wanted to know if Mink was serious.

“I reply to everybody, whether they’re 8 or 73,” he says. “I didn’t 100 percent believe it was real.”

It was one thing to play ball in your driveway, but Mink hadn’t undergone any sort of formal conditioning, nor played competitive ball, since the Soviet invasion of Hungary.

There was no way he could match the speed and intensity of the 19-year-olds he’d be playing against, but years of swimming, golf, tennis, skiing, and other activities had kept him at an enviable fitness level. More than that, he had what every athlete needs – a little talent, a strong dose of moxie, and a whole lot of heart.

The season was already under way, but Mink didn’t waste time. He sat in on practices and got to know his future teammates. He trained at his church gym and joined a senior basketball league, the Smoky Mountain Papas.

“The first game, I scored one basket,” he says. “I was so sore I could hardly stand up. When I got home, I thought, ‘Well, my basketball career is over.’ ”

Still, he ignored the naysayers and pressed forward. “I didn’t have anything to prove to anyone except myself,” Mink says. “I wanted to replicate a dream that got interrupted.”

•••

Growing up in Eastern Kentucky, Mink couldn’t imagine far beyond the confines of Vicco, where most men earned a living as his father did, deep within the bowels of the earth, clawing through rock to find coal. The area was too mountainous for most sports, but basketball was popular, and before long, Mink was a starter, earning a name for himself as well as the occasional free milkshake from the corner soda jerk.

He graduated from high school – the first person in his family to do so – and accepted a scholarship to Lees College in nearby Jackson, Ky. By the end of his freshman year, he had a 1949 Ford, a steady girlfriend, and a good shot at a scholarship at a four-year school.

Then the bomb dropped. Someone had covered the coach’s office in shaving cream, and school authorities accused Mink. Before he could plead innocence, he was kicked off the team and expelled.

“I went to the dorm, packed my bags, got in my little car, and drove home,” Mink says. “It was too late to get into college or get on a team, and I didn’t want to hang around.”

The next morning, he enlisted in the Air Force, and for the next 38 years worked as a journalist, garnering bylines in papers where his name had once been headline news as a ball player. In 1998, Mink retired, but he didn’t want to sit home and “vegetate.” He had mountains to climb, links to conquer. Age wasn’t about to stop him. Plus, in the back of his mind, the humiliating end of his college basketball career continued to churn. No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t let it go.

“I’d still like to know to this day who, and why, I was blamed,” he says. “I would dearly love to find the answer to that 52-year-old mystery. I hold no animosity, but it would be a great relief to me to find out what really happened.”

•••

Returning to college basketball at his age is physically humbling. His vertical leap barely clears 20 inches, less than half that of teammate Larriques Cunningham. His 6.6-second 40-yard dash is a relative crawl. At 6-feet tall, he’s half an inch shorter than the last time he donned a jersey.

The game, too, has changed. Along with his required 12-hour college course load – Spanish, computer science, US history, and criminal justice – Mink must learn new defensive and offensive schemes. Vintage moves perfected by players like Bob Cousy and Cliff Hagen – the Michael Jordans of their day – are outdated.

Still, Mink brings his own magic to the court, not so much in his athletic prowess as his strength of character. He knows he’s the 11th man on the team, and he only leaves the bench when the Raiders have a comfortable lead. So far, he’s only played once, making two free throws, in Roane State’s 93-42 victory over King College.

“I’ve been competitive all my life,” he says. “I like to be a winner. If I don’t win, I don’t get bitter, but next time, I think, next time I’m going to get that sucker.”

His determination and love for the sport have earned respect from his teammates. Sophomore Chase Bell says he thought Nesbit was joking when he told them Mink was joining the team, but on the first day of practice, they realized it was real.

“It was odd,” Bell says. “We didn’t want to be too rough on him, but as the days went on, we realized we could play hard against him. He’s just like a regular player. He gives you motivation, and you know, players like me, we need that kind of stuff. Every player’s going to have his bad days.”

In a few months, Mink will step off the court one more time, and the lights will dim permanently on his college basketball career. When that day comes, don’t look for him on the bench or in the bleachers – that’s not where dreamers live.

Instead, seek the shadowy corners, the obstacle-strewn paths, the harrowing chasms where limits meet determination and hopelessness meets conviction. That’s where dreams flourish, and that’s where you’ll find Mink, lacing up his shoes, living out his passions.