Images of America's West held up against today's reality.

Loading...

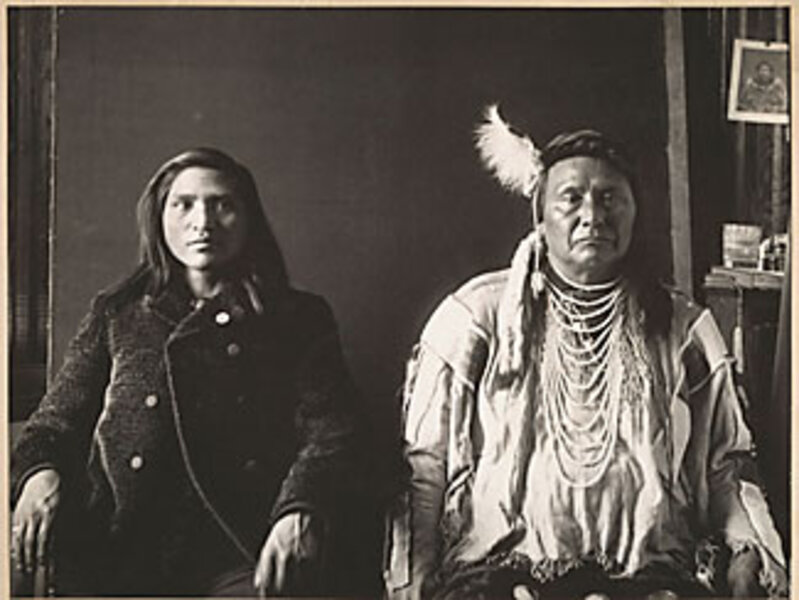

If one photo in a current Museum of Modern Art exhibition epitomizes the message of the show, it's Wells Moses Sawyer's 1897 portrait of two native Americans, "Chief Joseph and Nephew." Sitting side by side with equally rough-hewn faces are an older man (aka "Thunder Coming from the Water Up Over the Land") in colorful buckskin-and-feathers regalia and his nephew, Amos F. Wilkinson, wearing drab, ordinary garb (page 40). There you have it: the poetry and prose versions of the West, Thunder versus Amos, the romance and the reality. "Into the Sunset: Photography's Image of the American West" (on view until June 8) so overflows with such contrasts, it might well be titled "Paradise and Paradise Lost."

The exhibition, divided into landscapes and portraits of Western archetypes, includes 138 images by 75 photographers, ranging from the dawn of photography in the 1850s through 2008. Big names, like Timothy O'Sullivan, Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Dorothea Lange, and Cindy Sherman, are present.

But there's a division as sharp as the Continental Divide between their visions. The 19th-century photographer-explorers and the early 20th-century artsy pictorialists present a vision of the West as a new Eden, bursting with endless vistas, scenic grandeur, and boundless opportunity. Not only the majestic landscapes but the early inhabitants come straight from historian Frederick Jackson Turner's frontier thesis, which attributed American traits like self-reliance and rugged individualism to the westward migration. Pictures abound of American icons like scruffy miners, fearless cowboys, and plucky homesteaders – heroes all.

Then there are their contemporary, decidedly unheroic, counterparts: bikers, street hustlers, complacent suburbanites, would-be starlets, and hippies. Modern images of the landscape also slant toward decay. Suburban tract houses choke once-scenic valleys, while pools of toxic waste disfigure mining towns. In the "then" and "now" contrasts, "now" looks pretty noir.

Take the two Adamses. More than any other modern photographer, Ansel Adams bolstered the myth of the West as an unspoiled paradise. His view of "Mount Williamson, Sierra Nevada from Manzanar, California" (c. 1944) is an image of sublime beauty – a celestial pyramid lit by rays of ethereal light. In "Burning Oil Sludge North of Denver, Colorado" (1973), Robert Adams (no relation) captures another facet of the West. Next to a cranking oil pump – an inky calligraphic form on the snowy terrain – a plume of black smoke widens to almost fill the sky.

Heavy-handed polarities abound, often in pictures hung on facing walls. In "Watching the Dancers" (1906), Edward Curtis, the great mythologizer of indigenous dignity, glorifies four Hopi women in traditional dress as noble savages. Juxtaposed are Gary Winogrand's giddy women at a rodeo in "Fort Worth, Texas" (1974-77), who wear fringed and beaded leather halter-tops that barely cover their breasts.

Erwin E. Smith's "Mounting a Bronc" (circa 1910) pictures a cowboy hopping on a horse, ready to gallop across the plains, an image straight from "saddle-up" Western films. Contrasted with his dynamism is Justine Kurland's "Astride Mama Burro, Now Dead" (2007), showing a broken-down, old hobo, dry and dusty as the land, trudging along as a freight train recedes in the distance.

In "U.S. 97, South of Klamath Falls, Oregon" (1973), Stephen Shore juxtaposes real and ideal, showing a hyper-sublime image of the golden West on a roadside billboard, which is planted on the actual fenced-off landscape (see page 39).

Philip-Lorca diCorcia stages dramatic color tableaux of drifters like "Major Tom" (1990-92), above, a hustler from Kansas City, lying sprawled atop John Lennon's star on the Avenue of the Stars in Hollywood. "Imagine," indeed, as Lennon sang, what dreams drove this youth West and what he found in their place. Katy Grannan's "Nicole, Crissy Field Parking Lot" (2006) shows another La-La Land denizen, a platinum blonde in a pinup pose casting a harsh shadow from her contorted form. Mascara runs in dark streaks like a whip lash down her neck. Grannan calls her subject a "new pioneer" and has said, "Many of us are still looking for whatever it is we believe the West offers – reinvention, escape."

Although it appears contemporary photographers highlight exclusively the failure of the promise of the West, not so, says Eva Respini, MoMA's associate curator of photography. Instead of viewing her subjects as pathetic, "Grannan sees inspiration in them," Ms. Respini says, as the photographer explores "the complex psychology of what happens when you go West to reinvent yourself and it doesn't go according to plan."

Joel Sternfeld sums up the downfall of the fantasy of the West in a striking landscape. "After a Flash Flood, Rancho Mirage, California" (1979) shows, in the background, a typical housing development. In the foreground it has fallen literally into ruin, a driveway and car washed away by a mudslide.

Which raises the question: Was the lure of the West as a land of infinite bounty always a mirage, a lovely illusion created by early photographers? Or was it the imprint of humanity – railroads, highways, parking lots, industrialization, factory farms, and suburban development – that transformed the Wild West?

"The nugget of the show is thinking about the West as an idea rather than as a place," says Respini, "and how photography has had such an influential role in how the image in our popular imagination has been formed."

The exhibition feels very timely. It reflects the present mood of decline based on economic fact as well as the "pick-yourself-up" mandate embodied in America's past "can-do" mentality that President Obama hopes to reinvigorate. While post-1960s photographers debunk the idealized image of the West, perhaps the romantic and realistic views are both necessary. As Respini says, "We need these myths to perpetuate the national identity of a young, entrepreneurial country breaking from the Old World."

In 1851, the editor Horace Greeley popularized the slogan, "Go West, young man, and grow up with the country." Now that the country's grown up and the West no longer looks so enticing, it would seem our salad days, with their beckoning promise and potential, are vanished. As Joni Mitchell's lyrics put it: "Don't it always seem to go,/ That you don't know what you got till it's gone?/ They pave paradise and put up a parking lot."

Maybe what we think of as our hardy American identity was mostly a myth. But it's one that continues to inspire – and that we need now more than ever. Like the young boy watching his ideal hero ride off into the sunset in a classic 1953 Western, one wants to cry, "Shane, come back!"