The price of milk: Low for milk drinkers, but sinks family farms

Loading...

| Plainfield, Vt.

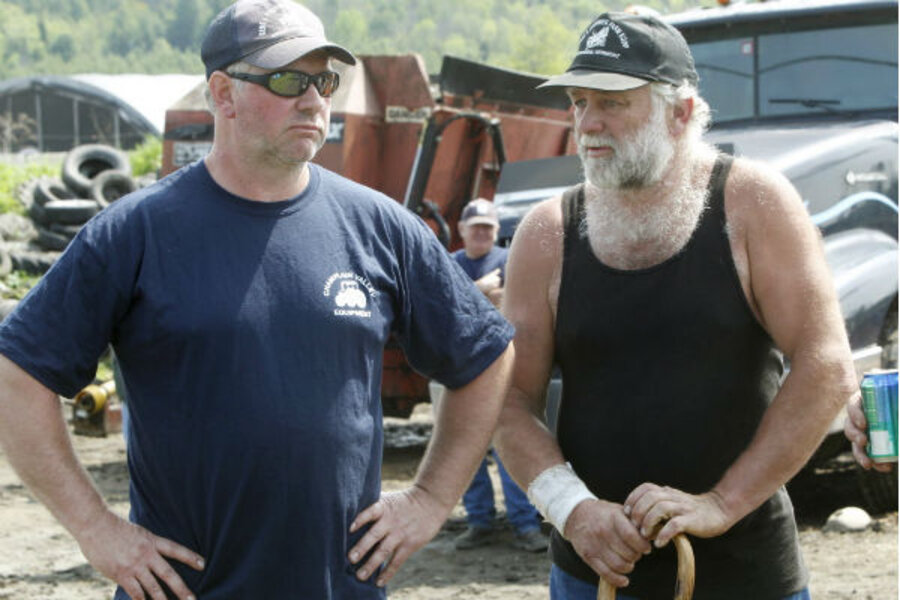

The MacLaren brothers are third-generation dairy farmers, but they will likely be the last in their family.

After working all their lives on the hillside farm in Vermont that their grandfather bought in 1939, rising to milk cows at 3 a.m., even in blizzards and sub-zero temperatures, they decided to call it quits, auctioning off their roughly 200 cows and equipment ranging from stalls and hoof trimmers to tractors and steel pails.

The sale marked the end of the last dairy farm in Plainfield — a small town that once had several dozen — and the 14th dairy farm to go out of business in Vermont this year. A few small dairies have opened, but overall, the number of farms continues to drop in a state long known for its milk and cheese. Farmers say they can't make ends meet when milk prices are low and feed and fuel costs keep going up.

"The day of the small farms, I think, is gone," said Steve MacLaren, 54. "A lot of people are going to hold on as long as they can, but we decided not to. Why struggle on it any longer?"

Economic issues aside, the MacLarens are tired of being tied to the farm seven days a week. They plan to keep the land and grow feed — corn and grass for hay and silage — on more than 500 acres.

"No matter what, you've got a sick cow or a cow having a calf, you've gotta be around whether it's 1:00 in the morning, or it's whatever time, you've got to take care of them," said Michael MacLaren, 48. "But if you've got a tractor break down, you can walk away from it. It's just a long hard grind, and I decided I'd like a change."

While the number of dairy cows in the U.S. hasn't changed much, the number of dairy farms has been dropping as small farms either go out of business or consolidate to become more competitive and cost effective.

The number of dairy farms nationally has dropped from nearly 92,000 in 2002 to less than 70,000 in 2007, according to the last agricultural census, which is being updated this year.

That's not the whole picture though. The number of small farms, with 100 to 199 cows, fell from about 11,000 to about 9,000 during that time, while those with more than 1,000 cows grew from about 1,300 to almost 1,600.

The shift has affected states like Vermont and Wisconsin, which have strong dairying histories, but tend to have smaller farms than other major milk-producing states like California and Texas.

Wisconsin has lost nearly 200 herds so far this year and now has about 11,600.

The farm closures are likely to continue with milk prices expected to keep falling this summer.

"It's a dying business," said Ron Wright, owner of Wrights Auction Service in Derby. He expects to do twice as many auctions this spring as last — eight to 10 auctions in Vermont and one in New York.

The U.S. had been gradually losing dairy farms for decades, but then milk prices plummeted during the recession and fuel costs soared in 2009. Vermont lost 52 dairies that year, while Wisconsin lost 519.

Prices have rebounded since, although they are expected to sink again to as low as $16.50 per hundred pounds this summer, said Diane Bothfeld, Vermont's deputy agriculture secretary.

"It will be a very difficult year," said Bothfeld, who expects the auctions to continue.

The loss of small farms hurts local economies and the many businesses that rely on them, such as feed and tractor dealers and veterinarians, she said. It also could be a problem for Vermont tourism, which is closely tied to bucolic images of the state's mountains and dairies, although Bothfeld said she thinks much of the land will stay in farming.

Vermont watched the number of its dairies drop in the past 20 years from 2,272 to 977 this May. At the same time, its milk output has stayed relatively the same as surviving farms grow. In the past five years, the average dairy size has grown from 125 to 135 cows in Vermont.

"To succeed in farming it seems like you really have got to diversify or go big," said Jennifer Lambert, 26, of Washington, one of the few new dairy farmers in Vermont.

She and her husband have leased his uncle's farm, where they produce organic milk, which commands a higher and more stable price than conventional. They also grow livestock feed and picked up a $7,500 seeder at the MacLaren's auction on May 16.

"It's very difficult to get started in this," said Jesse Lambert, 30, of the investment. They can't afford to buy the farm — or borrow the more than a half million dollars to do it — so were lucky to lease it, he said.

The MacLarens didn't watch as their cows were led one by one into the auction ring, where bidders sat on bales of hay. Michael MacLaren said he and his brother will miss the animals some.

"But you make the decision and have the courage to go through with it and you do it," he said. "That's the way it's gotta be."