In New Orleans, a plan to bring back a favorite vegetable

Loading...

| NEW ORLEANS

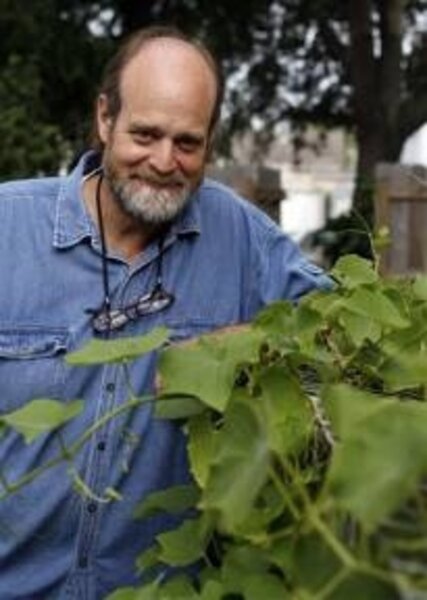

Lance Hill has a vision.

He sees neighbors swapping mirlitons over the back fence, like they used to do. He sees blighted lots covered with tidy horizontal trellises, where the big leaves of mirliton vines form shade canopies for neighbors to sit under, with mirlitons hanging down for the picking. He sees microbusinesses built around mirlitons, maybe even "Ninth Ward Mirliton Jam."

But the Mirliton Man's first step is to "restore the traditional mirliton variety that was lost over the last several years in particular. I think it was wiped out by Katrina," Hill said. "I want people to be able to grow them like they did 30 years ago, without a variety of sprays in the garage."

After the big storm, Hill and other growers, including some commercial growers in Plaquemines Parish, tried to root new plants from store-bought mirlitons (or chayotes, as most of the country knows them). But supermarket varieties are from Costa Rica. They grow at elevations of 3,000 to 4,000 feet and need a lot of chemical help to survive in south Louisiana.

"We needed to find the traditional variety," Hill said — and the heirloom ones don't have names. After a couple of years hunting outside the flood zone, he found Ervin Crawford in Pumpkin Center, who had gotten his mirliton starts from another farmer in Tangipahoa Parish. The original was purchased in Kenner when that town consisted of truck farms.

Hill started growing the backyard vegetables. By Mother's Day, Hill had 18 potted mirliton plants, enough to give away in a project with the Crescent City Farmers Market. Their newsletter advertised the "Adopt-a-Mirliton" project, for serious growers who would like to raise a mirliton vine, with the understanding that they will bring half their crop back to the market and help propagate the variety.

"We got an incredibly enthusiastic response [to] Lance sitting at a table in the middle of the market with the beautiful plants he'd grown," said Emery Van Hook, director of markets at marketumbrella.org, which runs the Crescent City Farmers' Market. "Our shoppers are incredibly curious and passionate about local food and local food culture, and I think it's one of the most culturally significant products at the market."

Last fall when mirlitons were in season, the market had two mirliton vendors, Van Hook said.

"They sold out almost as soon as they put them out on the table," she added.

"Serious growers" who contacted Hill were given the plants. The summer's early heat, and then the rain after it, took a heavy toll, but there have been survivors, too.

Ann Butcher's plant is now blossoming, after a period of "awful peakedness" when she thought it wouldn't survive, she said. Butcher used to live in an old house that had its own mirliton vine.

"Everybody used to have them," she said. "They're not all over the place any more. You never bought them; you used to just go pick them somewhere.

"I had been thinking of planting [mirlitons] anyway" when she saw Hill's notice, Butcher said. She doesn't garden much, but she decided she really wanted to plant things that "are hard to come by. I planted a fig tree that was really doing well, except the birds took all my figs."

When visiting Butcher in the Bywater neighborhood, Hill realized that many people have quit growing the perennial at home because so many people now have wooden security fences instead of chain link, a natural trellis.

Pamela Broom got a mirliton plant, too.

"It's still alive, bless its little heart," she said. "It's still green and hanging in there." She is growing it in her porch garden and plans to train it up the railing.

Broom also happens to be the farm-yard director of the New Orleans Food and Farm Network. "We would love to explore working with Lance on this," she said.

Growers were asked to keep records of their vine: watering, fertilization, diseases, etc. Hill came up with a 16-page growers guide, which also includes instructions for building a sturdy horizontal trellis out of bamboo, and much, much more. Hill also has enlisted help from experts at the LSU AgCenter.

Van Hook said the CCFM Web site — www.crescentcityfarmersmarket.org — has posted the growers guide, with links to Hill's Flickr site of photographs that show trellising and more. Hill also wants to partner with the CCFM on an international recipe database. He's found recipes by the dozen by searching the Internet under the vegetable's many names.

"The research he's done blows my mind," Van Hook said. "I had no idea when he came to us with this project the international significance of this food."

Hill is a font of mirliton knowledge. He has visited Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean, where mirlitons "have a cult following. Escaped slaves could take a couple into the mountains and [they] literally help them survive. They could make fabric out of it, and hats, and eat it, and could feed the tendrils to their chickens."

All parts of the mirliton are edible, it turns out. In areas without nematodes in the soil — not the case in the New Orleans area — the roots can be harvested and eaten. Some countries feed the roots to cattle. In Taiwan, "dragon-whisker vegetable" is mirliton shoots.

Other names: Christophene, mango squash, pear squash, vegetable pear, choko, pepinella, pepinello, xuxu, xoxo, sayote, tayota. "Cho-cho," as it's called in Jamaica and Belize, also is a word for "pet." Guess where it's called a mirliton, besides here? In Haiti, which makes one wonder if this is another culinary link to the St. Domingue slave revolt.

This squash is Hill's hobby. Trained as a historian of the civil rights movement, he is executive director of Tulane University's Southern Institute for Education and Research, a race and ethnic relations center.

"The mirliton is an antidote from my day-to-day work," he said.

Hill said those with questions about his project may contact him through mirlitons@marketumbrella.org.

Editor’s note: For more on gardening, see the Monitor’s main gardening page. Our blog archive. Our RSS feed.

You may also want to visit Gardening With the Monitor on Flickr. Join the group (it’s free) and upload your garden photos. Join the discussions and get answers to your gardening questions.