Under Fire: Journalists in Combat: movie review

Loading...

The sometimes agonizingly powerful documentary "Under Fire: Journalists in Combat" is built around some staggering statistics: Only two journalists were killed in World War I. Sixty-three lost their lives in World War II. And in the past two decades, almost one journalist per week has been killed.

In Iraq, the most lethal of war zones for journalists, the total killed is close to 200, which exceeds the toll for journalists from both world wars and Vietnam combined. The International News Safety Institute now counts 1,397 media professionals dead in the 10 years from 1996 to 2006 in 105 countries. This is not even to mention the numerous kidnappings and incidents of torture.

To understand why reporters on the front lines are in such increased danger, and to comprehend how they cope with their lives, director Martyn Burke interviewed a broad range of journalists, male and female, from outlets ranging from The New York Times and Reuters to the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation and The Associated Press. For insight, he brought in psychiatrist Dr. Anthony Feinstein, who has written extensively on the subject and treats journalists healing from trauma.

The film, which was recently shortlisted for an Oscar for best documentary, could have used more testimony from those who have successfully recovered and how they did it, and more information about how state and federal institutions are coping (or not coping) with the rehabilitation process. But the movie is nevertheless an eye-opener.

The overriding question it poses: Why do these people continue to do what they do when it is clear that reporters, like soldiers, are now, in a paradigm shift, considered fair game by enemy combatants?

Feinstein has said in interviews that he believes the answer is in some measure genetic. "They have this drive that takes them back into conflict zones repeatedly and I believe to do that, you've got to have a certain biological predisposition," he told the Los Angeles Times.

The interviews in "Under Fire" certainly bear this out. Even those journalists who deny being "war junkies" come across as just that. Reuters photojournalist Finbarr O'Reilly talks about the need to "get into this war. You sort of resign yourself to the fact that you're probably going to get hurt and just hope that it isn't too bad when it happens."

CBC correspondent Susan Ormiston talks about the difficulty in wrenching herself away from her home to go on assignment. "The hardest part is the week before you go because you look at your children and you question why you go. Women never stop being a mother no matter where they go." She describes the surreal experience of being in an active combat zone while talking on the phone to her daughter about the Easter Bunny.

Asked if the war experience is different for women, she answers, somewhat defensively, "There are plenty of men who are fathers." But Christina Lam of The Sunday Times of London describes the special harassments of being a woman in a war zone, especially in the Middle East, where being groped is a regular occurrence and baggy clothes are standard. "You develop sharp elbows," she says.

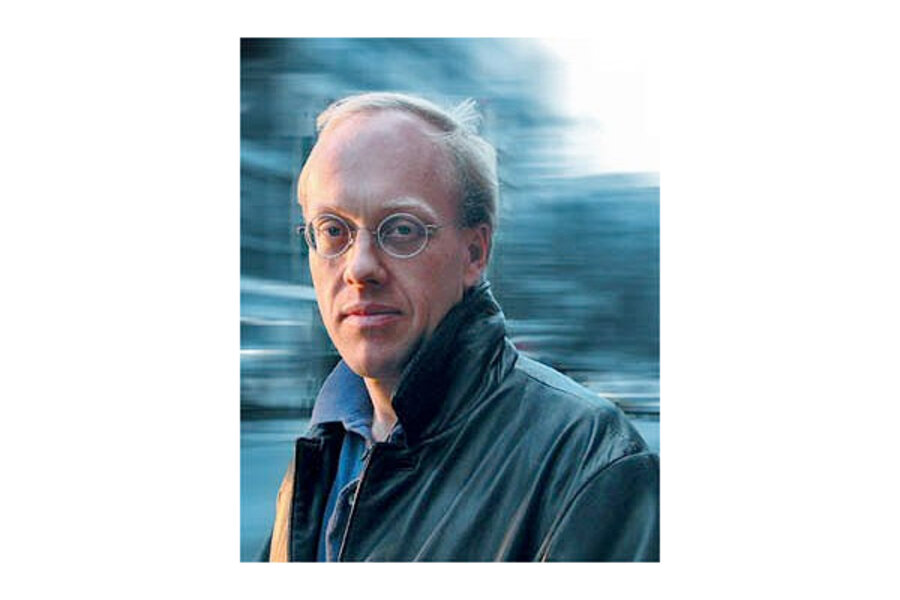

Former New York Times reporter Chris Hedges, author of the memoir "War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning," says, "In the same way a drug physically breaks down an addict, I was broken down by war." We see live footage of BBC special correspondent Jeremy Bowen at the moment when a colleague is killed in full view of him perhaps 50 yards away. Another reporter talks about how he told a little girl to wait for a photo while he went inside a building for a moment only to find her shot dead by a Bosnian sniper when he returned. Many of the correspondents harbor an overriding guilt about surviving or placing others in danger.

Is it worth it in the end to lose your life for a picture? An even larger question: How moral is it to depict as a profession the suffering of others? The fame and honor that sometimes come with their work do not seem to be the motivating forces behind these men and women.

Perhaps the most wrenching interview in the film is with Paul Watson, who won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994 for his photo of a dead American soldier being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu – a photo that helped spur a US foreign-policy change in the region. He is still riven by his decision to take the shot. The mother of the slain soldier refused to speak to him. Rebuffed in his search for forgiveness, he says today, "I don't feel like a good person anymore."

But he also says about himself and his compatriots: "Don't ask for sympathy. You made the choice. Ask God's sympathy if you must, but don't ask people to feel sorry for you." Grade: A- (Unrated)