'War Witch' brings the plight of an African child soldier to horrifying life

Loading...

Set in sub-Saharan Africa, “War Witch” brings us shudderingly close to the life of a 12-year-old girl who lives peacefully with her mother and father in an isolated village until pillaging rebels order her to shoot her parents. Komona, beautifully played by Rachel Mwanza, who has never acted before, has no choice: If she refuses, the rebels will kill her and hack her parents to death with a machete. So begins her initiation into the atrocious world of a child soldier.

Nothing in “War Witch,” which was nominated this year for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar, can match the sheer primal horror of this opening sequence. But the writer-director Kim Nguyen, who lives in Canada, is not concocting imaginary horrors. The enforced slaying of parents is a well-known rebel tactic for breaking the spirit of these children, who soon enough will learn to tote AK-47s and perpetrate their own atrocities. At an age when many of them are hardly formed, they have effectively been rendered soulless.

Or have they? What makes “War Witch” more than a catalog of horrors is the possibility that, despite everything, Komona can be redeemed. The film, in a sense, is about her two-year odyssey to lay her parents’ spirits to rest. By age 14, having been impregnated by a vicious rebel commander, she is pregnant and on the run. She wants her baby to live unencumbered by the abominations that brought him into the world. It’s an impossible task, of course, but her attempts at salvation are no less powerful for being so insurmountable. The rebels’ supreme leader, Grand Tigre Royal (Mizinga Mwinga) believes that Komona, because her ghostly visions enabled her to survive an ambush by government soldiers, is a sorceress. Although she sees phantasms of the dead all around her, deep down she knows otherwise. She knows she is mortal.

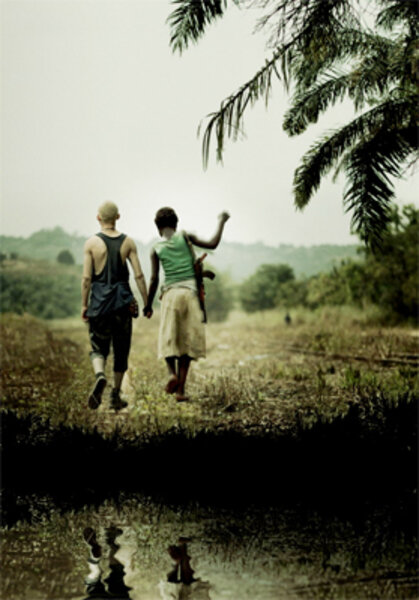

There is an all-too-brief interlude when she runs away from the rebel camp with a fellow soldier named Magician (Serge Kanyinda), an albino 15-year-old who is more trickster than magician. He wants to marry Komona, but her father once told her she can only marry a man who brings her a very rare white rooster. And so, in the midst of so much misery, these two go in search of a white rooster, which also allows Nguyen the opportunity to deftly depict the bustling life of the surrounding villages. In these sequences Komona and Magician betray just how young they really are. He may tote his rifle, but, in these unembattled surroundings, it’s just a kid’s prop (albeit a lethal one). You want everything to turn out for the best with these two because, although Nguyen doesn’t idealize them, they seem like incarnations of all those children who have been ravaged by war. They are babes in the woods, a very dark woods.

I wish Nguyen had toned down some of the film’s magical realist tropes, which are more clunky than spooky. And although he usually films from Komona’s point of view, his camera sometimes strays unnecessarily into amorphous “objectivity.”

“War Witch” is most effective not when we are looking in on Komona but when we are inside her head. When she says that, in order to survive in the rebel camp, she “had to learn to make the tears go inside my eyes,” our identification with her is total. Grade: B+ (Unrated.)