'The Finest Hours': Coast Guard participant remembers the historic rescue

Loading...

Andy Fitzgerald had a purpose in hanging around the Coast Guard station in plain sight.

"I was the lowest class engine man there, and I didn't get to go out too much," he recalled. "I'd never really been out in a rescue of any size where you're really rescuing people's lives when they were really in danger."

"I was really trying to figure out how to go on that rescue," he added.

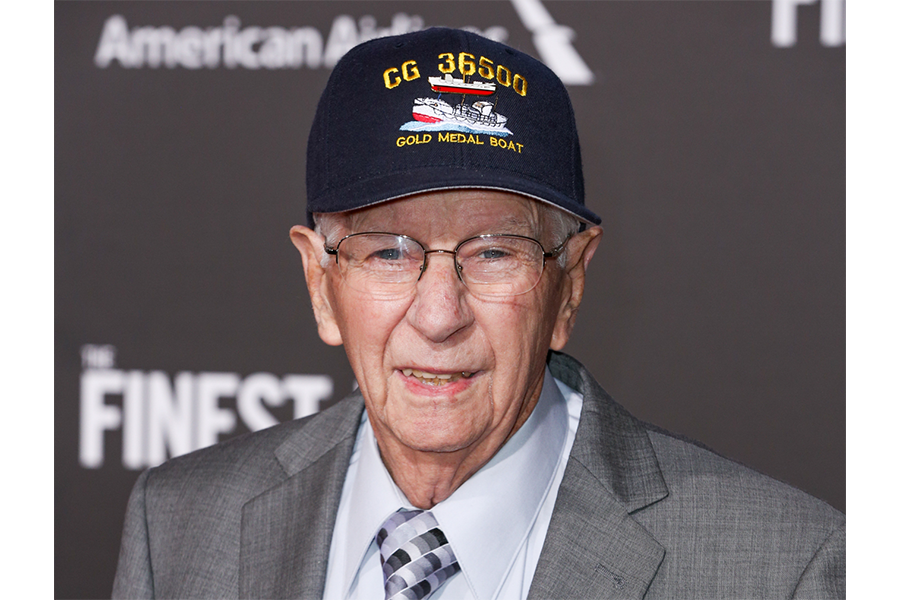

Fitzgerald got what he wished for, and more, when he volunteered to be the boat engineer to rescue men off a stricken tanker on Feb. 18, 1952. He and the three other Coast Guardsmen on the CG36500 were awarded the Gold Lifesaving Medal, the Coast Guard's highest honor, for plucking 32 men off the SS Pendleton.

Considered to be the greatest small boat rescue in Coast Guard history, it has been the subject of several books and now, a major movie. "The Finest Hours," based on the book by the same name by Michael Tougias and Casey Sherman, was partially shot in Chatham, and is now in theaters.

At 84, Fitzgerald is the last surviving participant in the historic rescue.

Fitzgerald said he was never afraid.

"I wasn't worried about the boat. And the coxswain (Bernard Webber) was one of the best in the Coast Guard. I don't think I was afraid at all any time during that night," said Fitzgerald, who was 20 at the time.

In the grip of a fierce nor'easter, with winds in excess of 80 mph, the Chatham Coast Guard Station was a busy place that February day. One crew had already been dispatched from Stage Harbor in a 36-foot boat to rescue the crew of the Fort Mercer, a 503-foot tanker that had split in half nearly 30 miles southeast of Chatham. A third 36-foot lifeboat left from Nantucket.

Boatswain's Mate Webber and Seaman Richard Livesey, along with Engineerman Melvin Gouthro, had been out all day, retrieving fishing boats that had been torn from their moorings.

When they returned cold, wet, and tired, they were met at the pier by Officer In Charge Daniel Cluff who told Livesey and Webber to drive to Orleans and try to spot a second tanker, the Pendleton, which had also split in half and was drifting by the Cape.

The Pendleton and the Fort Mercer were WWII T2 tankers. But the design had a fatal flaw. Their welded seams were subject to fractures under the stress of rough seas, especially in cold water.

As waves pounded the 503-foot Pendleton in the early morning hours of Feb. 18, crewmen heard loud creaking and grinding noises, then a sound like ripping tin.

From the top of a hill overlooking Nauset Beach, Webber and Livesy spied "a ship, rather a half of a ship, black and sinister, galloping along up and down huge waves, frothing each time she settled back into the sea," Webber recalled in his book "Chatham: The Lifeboatmen."

Back at the station, Gouthro told Fitzgerald he didn't feel well.

"Why don't you go to bed and sleep?" Fitzgerald said he told him.

Born in Brockton, Rocky Marciano's town, Fitzgerald was draft age, with the Korean War still raging, when he graduated from high school.

"I knew I was going to get drafted. In my mind I would have a very hard time to pick up a rifle and shoot at another person," he recalled. He chose the Coast Guard because they were in the business of helping people, not killing them, he said.

Fitzgerald hadn't seen the mountainous seas or felt the heavy wind that Webber and Livesy experienced from the hilltop in Orleans. And he hadn't been over the infamous Chatham bar when storms spawned steep powerful waves that could wreck even the most seaworthy vessel.

Webber knew its power well and had pulled dead men out of the water there.

"I knew that taking a lifeboat out over the Chatham bar would be risky business, with little chance of success," he wrote in his memoir.

"I didn't know it (the danger), but I don't think it would have made much difference to me. I was going to go on that boat," Fitzgerald said.

Station chief Cluff, a WWII veteran with commendations as an assault boat coxswain, was new to the station and didn't really understand the danger of the Chatham bar, even as he ordered Webber to cross it.

"He had to do something," Webber wrote in his book. "There were certainly men aboard the (tanker) sections and they needed help."

Even so, Webber said a "sinking feeling" came over him when Cluff told him to assemble a crew and head out to the Pendleton.

Ervin Maske, a seaman who was hanging around the kitchen waiting for transport out to his post on the Pollock Rip Lightship, volunteered right away.

Livesey also said he'd go.

But when Webber went looking for Gouthro, he encountered Fitzgerald who was standing nearby, bored and anxious to go.

"He says, 'Where's Gus?'" said Fitzgerald, who told Webber that Gouthro was sick.

"'I'm going to go with you,'" Fitzgerald said he told Webber.

The lighthouse beam swept overhead Webber as he moved into position to enter the field of breakers roaring away in the darkness. He called the station twice, hoping he'd be ordered back, but was told "it was imperative that we continue out to sea."

Webber told the crew to hang on, revved the motor, and charged into the first wave. The boat flew up into the air and landed on its side. Starved of fuel, the engine stalled and Fitzgerald scampered below decks to re-prime it and get it started. It was barely upright when it was hit by another wave that shattered the windshield, carried off the compass, and knocked Webber down.

The waves grew larger beyond the break, and Webber had to constantly slam the engine into reverse to slow the small lifeboat down as they raced down the back of waves, afraid they might bury the bow at the bottom and be sunk.

Without a compass, Webber headed east. He sensed the tanker before he actually saw it. Like a black hole, it was there in the maelstrom, unseen but present, a "screeching hissing sound" audible above the wind, Webber said.

He had Fitzgerald crawl forward and turn on the searchlight in the bow. They were facing into the open end of the ship, towering 30 feet above them.

"Just a white crawling mess, and it would just rear up high in the water, then settle back down with a crashing and a banging," Webber told Russell Webster and Theresa Barbo in their book "The Pendleton Disaster."

The Pendleton crew swarmed over the side, descending the 30 feet on a long rope ladder.

"When Bernie saw that, he drove along the hull to get to that ladder," Fitzgerald said. "I was up front and we went along the side and got up under that ladder and when they'd come down, I'd help them off and into the boat."

Given the enormous swells, many jumped and had to be pulled from the icy water. This was where Webber's seamanship, his familiarity with the 36500 really showed, as he had to time the roll of the tanker and the waves while trying to get to men without hitting them, damaging his own boat, or pinning them against the Pendleton's hull.

Unfortunately, one man, George Myers, was killed as a wave launched the rescue boat up against the ship's hull.

The 36500 was built to hold 30, but space was tight and the boat rode alarmingly low in the water. "What Bernie said he was going to do was just head for shore, that we probably won't get back into the harbor, 'So I'm just gonna beach the boat and everybody will jump off,'" Fitzgerald recalled.

By some miracle, they spotted one of the red channel markers that marked the entrance to the harbor, and Webber gave the station notice of his return.

"It was obvious my father or mother heard it, that the boat was coming up the harbor," said Bob Ryder, 74. As a fishing family, the AM radio in the kitchen was always tuned in to boat chatter.

"They said, 'Let's go!'"

Word of the rescue also reached town meeting and most left to go to the pier. Fitzgerald thought there were around 100 there when they pulled up.

There was no applause, Ryder said.

"It was very quiet. People were kind of shocked or awestruck," he said. "I don't remember hearing anything except the wind and 'Oh my,' 'Wow,' a little bit of muttering.

"I think they were kind of stunned to see what had happened and what we had done," Fitzgerald said.

The survivors were taken to the Coast Guard Station. Some went to the hospital.

"When I got there, they were all kind of in one room, the survivors and the crew that was left at the station. They were all pretty happy, I'll tell you. I was pretty happy," Fitzgerald said.

The 36500 boat crew separated soon after that rescue, to new postings, or in Fitzgerald's case, for a civilian life as a salesman in Aurora, Colorado.

"My first thought was that was a very tough job and I was able to do that," Fitzgerald said of the rescue. "Later in life when I'd get a job that was a little hard, I'd think back to that thing many years ago and it was a lot tougher than this is going to be, and I would do the job."